A few years back I wrote an article on the whole idea of “… but it’s a dry cold.” I mentioned it was one of those weather sayings that really gets under my skin, to the point that I just cannot keep my mouth shut when I hear it. Honestly, I will butt into a discussion with people I don’t even know.

So, what happens to me just the other day? Someone I am talking to about running outdoors in the winter (something I am not a fan of, I actually like my treadmill) mentions that someone on the radio was talking about how the day felt so cold because it was such a humid day. Well, I nearly lost it.

Read Also

The lowdown on winter storms on the Prairies

It takes more than just a trough of low pressure to develop an Alberta Clipper or Colorado Low, which are the biggest winter storms in Manitoba. It also takes humidity, temperature changes and a host of other variables coming into play.

Just kidding. But it did raise the hackles on the back of my neck, and I had to launch into an explanation of why that’s just a big pile of you-know-what!

After doing another quick Google search on the topic I was not able to find much more new information from when I last wrote about this. The article I came across the last time I dug into this topic was written by Alex Hutchinson for the Globe and Mail back in January 2016. His article did a fairly good job hitting all the points I wanted to make. With that said, I am still going to make my best attempt at tackling this notion and will add a little bit more of my understanding of weather to the topic.

Looking at the saying, “but it’s a dry cold,” you are immediately referring to humidity — after all, it is talking about a dry cold versus a wet or damp cold. This suggests there must be something about humidity that affects how warm and cold we feel. This makes some sense, as we know when it is hot outside, the higher the humidity the warmer we feel. We cool ourselves by sweating. The water on our skin then evaporates, with some of the energy for this evaporation coming from the heat of our bodies. The quicker the evaporation, the faster we lose heat. When the humidity is high the air can’t “hold” much extra moisture and evaporation rates decline. Less moisture evaporates from our bodies so less cooling occurs, and we feel hotter.

Now, if we cool the air down to around 10 C, the only time we tend to feel cooler is when it is very moist outside, like when it is foggy or misty out. This once again makes sense as this extra moisture will actually cause our skin and clothes to become damp. The moisture on our skin will enhance heat loss through evaporation and quicker conduction of heat. Our wet or damp clothes lose their insulation value since moisture can conduct heat much quicker than air.

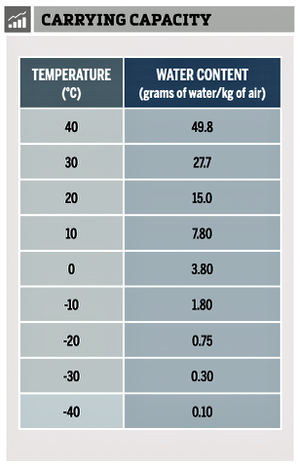

Once we drop temperatures down below freezing we do not have to deal with wet or damp clothes or skin, so that is off the table as a reason for feeling colder. Maybe during a very humid, cold day the moisture in the air will simply be enough to help transfer heat away from your body. The problem with this has to do with just how much water or moisture air at different temperatures can hold. The table at left shows just how much moisture air at 100 per cent relative humidity holds — which is the theoretical maximum amount of moisture.

You can see that once you drop below 0 C, the amount of moisture in the air at 100 per cent relative humidity is pretty small — small enough that it really has no impact on how much heat can be transferred. At 20 C there is about 15 g of water per kilogram of air. This value nearly doubles when you get to 30 C, or about an increase of 12.7 grams. So, it makes sense why it gets so uncomfortable when it is humid and hot outside. During the winter there is not much of a difference in the amount of moisture in the air between, let’s say, 0 C and -20 C, a total of 3.05 grams. It’s even less when comparing -10 C and -20 C: a difference of 1.05 grams. In the winter the air is just plain dry, no matter what the relative humidity is.

So, why do some people swear up and down that it feels colder when it is -5 C and humid compared to -20 C and dry? Well, there doesn’t appear to be a definitive answer, but there hasn’t been a ton of research on the subject either. The pure research that has been done did not find any differences in temperature between people in low- or high-humidity levels when it is cold out, yet people will argue until they are blue in the face that there is a difference.

That leaves us with a couple of possible explanations. The first is simply that our perception, and possibly the way we dress, is different when it is a few degrees below 0 C and we see snow, slush and water around us. Our minds take the environmental cues we see, and we expect it to be warmer than it really is, so we don’t dress the same or expect it to be as cold as it is. This then translates into us feeling colder than we should. The second explanation is that humid winter weather tends to be associated with cloudy conditions or lack of sunshine. We all know from living on the Prairies that a nice sunny day, no matter what time of the year, makes it feel warmer out, unless of course the winds are howling. In the winter, sunshine can make it feel up to 5 C warmer. Personally, I think it’s a combination of all of the above.

So, next time someone says, “but it’s a dry cold,” let them know that all cold is a “dry cold” and that feeling cooler in “slightly humid” winter conditions is either all in their head, they haven’t dressed properly, or it’s the lack of sunshine.