It’s time to talk about fall frost and the length of this year’s frost-free season. So far, most areas of agricultural Manitoba have not yet experienced frost – or have they?

Data for major centres shows a number of locations came close to frost on Sept. 12, and I found 10 to 15 locations did report a light frost on that morning, including my own weather station. While temperatures dipped to around -1 C at these stations, my own location had little frost damage. Let’s take a look at fall frost and the frost-free season.

Read Also

Students push for Manitoba road upgrades

Manitoba’s lack of higher-rated RTAC roads creates irritating highway detours and weight restrictions for farmers, University of Manitoba students told KAP.

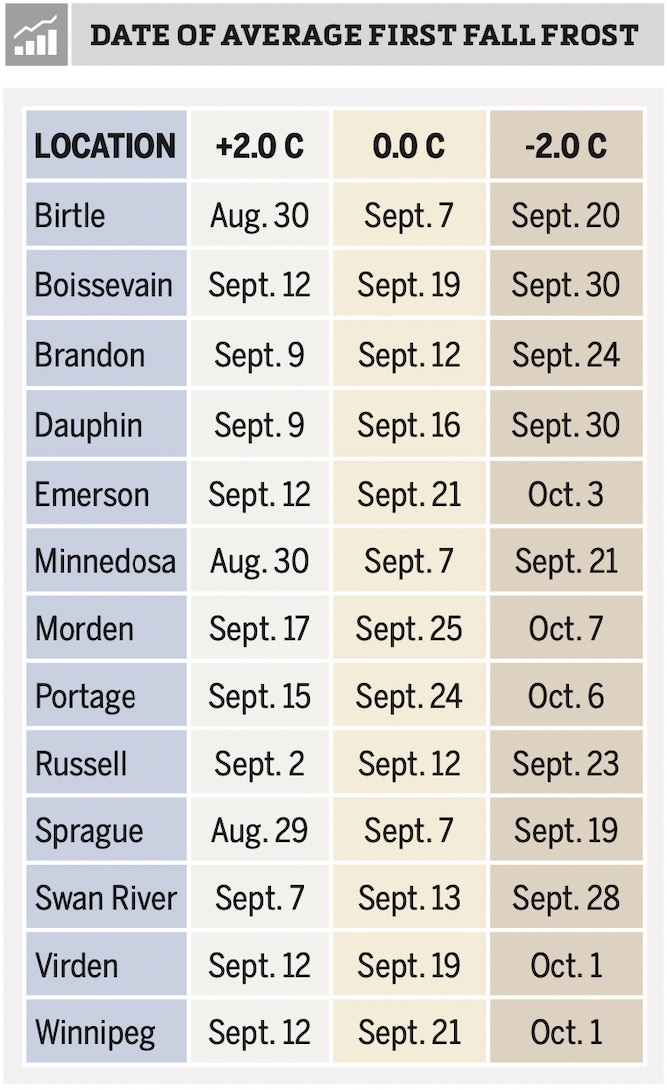

The first question I am usually asked about fall frost is about dates for the first frost in different areas of agricultural Manitoba. To analyze this, we must first determine how frost is measured or recorded.

The typical measurement is when the temperature falls below 0 C. We know frost can occur even when the thermometer shows temperatures above the freezing mark. In fact, research has shown ground-level frost can occur at readings as high as 2 C and even as high as 5 C.

This occurs more often in spring, before the ground has warmed, but under the right conditions this can also occur in the fall.

The difference between measured air temperature and actual temperature at ground level depends on location of the thermometer. Most record air temperature several feet above the ground and may not accurately reflect actual ground temperature. Also, the amount of vegetation nearby can trap heat radiating from the ground, giving a bit of a false reading.

You may recall that air near the ground can cool to a greater degree than air several feet above. This is because cold air is denser than warm air, so it tends to settle to the lowest points. If the area is relatively flat, the coldest air settles around the ground, resulting in ground-level temperatures cooler than the air several feet above.

While this is the norm, there are times when temperatures measured above the ground, at the level of the thermometer, are cooler than those recorded at ground or crop level.

Also, a frost with temperatures near freezing may not severely damage or kill a crop. It often takes temperatures colder than -2 C to kill crops, which is why temperatures lower than -2 C are often referred to as killing frost.

Let’s look at a few different temperatures, namely: 2 C, 0 C, and -2 C, to determine when we may expect the first fall frost. The data for several sites around southern Manitoba is in Table 1. These are the average dates on which these temperatures may be anticipated, based on the entire record of climate data for each location.

Remember, this is the average date and the standard deviation is three to five days, depending on location. This year may seem a little unusual so far, but it really isn’t.

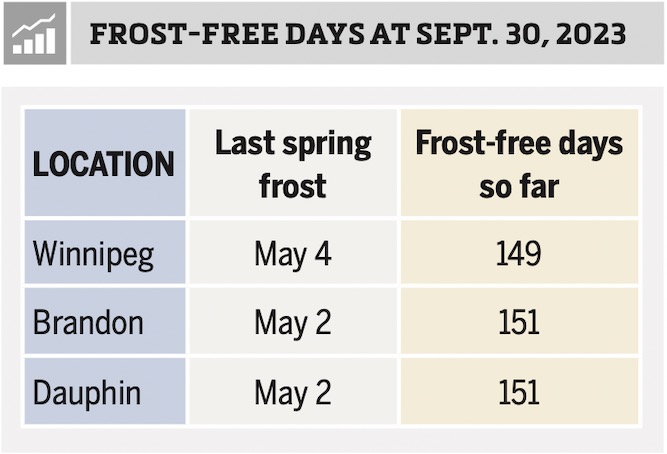

None of the three main reporting stations (Winnipeg, Brandon, Dauphin) report a sub-zero temperature so far this year, so I guess we are a little later than usual for the first fall frost.

To get the length of this year’s frost-free season, we use the date of the first fall frost and the date of the last spring frost. Last spring had a very early date, but it was also remarkably consistent, especially compared to other years. In Table 2 you’ll see the dates of the last spring frosts for those three locations.

The current weather forecast does not indicate temperatures near freezing between the time of writing and the end of the month, so I will use the date of Sept. 30 to calculate the frost-free season.

Long-term data for these locations shows the frost-free season is usually 115 to 125 days. So far this year, we are well beyond that. In fact, with such an early last spring frost and now a fairly late first fall frost, we are approaching record territory in some regions.

Winnipeg’s longest frost-free season is 157 days, in 1963, so a record will be set if it remains frost free until Oct. 9. Looking at the extended forecast, there is a chance it could happen.

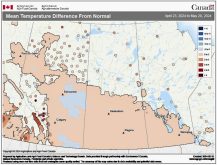

Please continue to send questions. In the next issue, it’s time to take our monthly look back at the weather, then peer ahead to see what the different long-range forecasts predict for the last three months of the year.

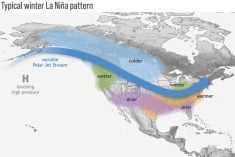

With the current El Niño strengthening and a 95 per cent probability that it will last through the winter, will it have an impact on our winter? We will see if any forecasts take that into account.