It seems like almost every winter the topic of the polar vortex rears its ugly head.

We even talked about it last winter, which was one of the warmest winters on record. So let us dig back into the archives and revisit just what the polar vortex is and how it can influence our weather.

A polar vortex is a large area of circulation (low pressure) in the upper atmosphere that is centred near both Poles and tends to be the strongest in the winter. As the upper air cools, it contracts and its height above Earth’s surface gets lower. This is what creates the area of low pressure in the upper atmosphere. It forms because in the winter the Poles are not receiving any solar energy.

Read Also

Winter grazing strategies offer cost relief for Manitoba cattle producer

How cover crops, straw and silage pile grazing fit in a western Manitoba rancher’s winter feeding plan — and how to make sure they meet cattle’s nutritional needs.

The counterclockwise flow around this region in the northern hemisphere means that the atmosphere flows from west to east. The stronger the air flowing around the vortex, the more circular the vortex tends to be. If the flow weakens, the shape of the vortex tends to get distorted, and we start to see large ridges and troughs form. Ridges are regions where the vortex has pulled northward allowing warm air to move northwards, while troughs are areas where it sags southwards allowing cold arctic air to push south.

We’ve know about the polar vortex for as long as we’ve had the ability to measure the upper atmosphere. It’s likely that it has always been a part of the world’s overall weather patterns, so it is not a new thing. Even the term polar vortex has been used in the literature since at least the 1930s. This is what gets me going when I hear people talking about this feature as it being a new thing — it’s not.

So, the question is: are the cold temperatures we normally see in the winter always the result of the polar vortex? The answer is yes and no. The polar vortex forms as a function of the cold temperatures that develop over our Poles in the winter. As I pointed out earlier, this is due to little to no solar input during this time of the year. The polar vortex, depending on the strength of the winds flowing around it, can create troughs and ridges that can allow cold air to surge southwards. The polar vortex is not the only feature that can influence troughs and ridges, so we can’t always say that every cold snap is directly connected to the polar vortex, but for this current cold snap it certainly was.

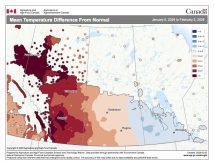

When the winds are strong, the polar vortex tends to stay fairly circular and remains in place generally over the Poles. When the winds weaken, undulations begin to form. These undulations are the ridges and troughs that I talked about earlier. Sometimes the polar vortex doesn’t form ridges and troughs, but simply shifts from its usual position. This is what has happened this year.

In late January, it shifted southward to lie over northeastern Canada. The size of the vortex, or upper low, stretches all the way from far eastern Canada into the eastern Prairies, with the southern edge right around the 45th parallel. The million-dollar question is how long will it stick around? Weather models are showing it breaking down towards the end of the month, so let’s keep our weather fingers crossed.

Since I have a bit more room, I thought I would revisit another perennial winter topic – wind chill.

In the winter we have a measurement called wind chill that considers the water vapour that is in the air, wind speed, and the actual air temperature. The wind chill factor indicates the enhanced rate at which the body will lose heat to the air. Our bodies help to keep us warm in the winter by trapping a thin layer of air near the surface of our skin. When it is windy, this thin layer is taken away and additional heat from our bodies is released to try and recreate this layer. This process repeats itself over and over, the higher the wind speed and the colder it is, the faster it goes.

In addition to this, moisture from our bodies is being evaporated — a process that uses up more heat from our bodies. A formula was developed to calculate the rate of heat lost around 1970 and in 2001 the wind chill formula was revised into what we hear about today.

The one thing that still can’t be built into the formula for calculating wind chill is a person’s physical activity, the sun’s intensity and the protective clothing being worn. All of these things can decrease the cooling effect of those cold winter winds, and this is where the problem seems to arise. Some people are arguing that wind chill values are not very good due to these variables. While you could take this argument, I do believe that wind chill values have a place in helping to determine just how cold it feels outside.

What I have an issue with is in how the media uses and reports wind chill. They tend to apply wind chill to inanimate objects like a vehicle. It just doesn’t work that way. Objects can only get as cold as the air temperature. If the wind chill indicates that it feels like it is -45 C but the air temperature is -25 C, then the coldest an object (including a person) can get is -25 C. What the -45 C means is you will be losing heat from exposed areas at a rate equivalent to an air temperature that is -45 C, but once you hit -25 C the object cannot get any colder. So, your car might cool off quicker, but it won’t drop below the air temperature.

If we look at the effect of cold temperatures on the human body, one of the first things our bodies do is contraction, which pulls blood away from the extremities of our body, conserving it to help keep our core warm. This leads to a greater risk of frostbite due to a lack of blood supply, and an increase in urine output. As we continue to cool you can develop hypothermia as you core temperature drops below 35 C. Early signs are shivering, fatigue, and numbness in extremities. Prolonged cold exposures can lead to a suppression of the immune system which can increase a person’s vulnerability of infections.

Hopefully I don’t have write more about cold weather this winter.

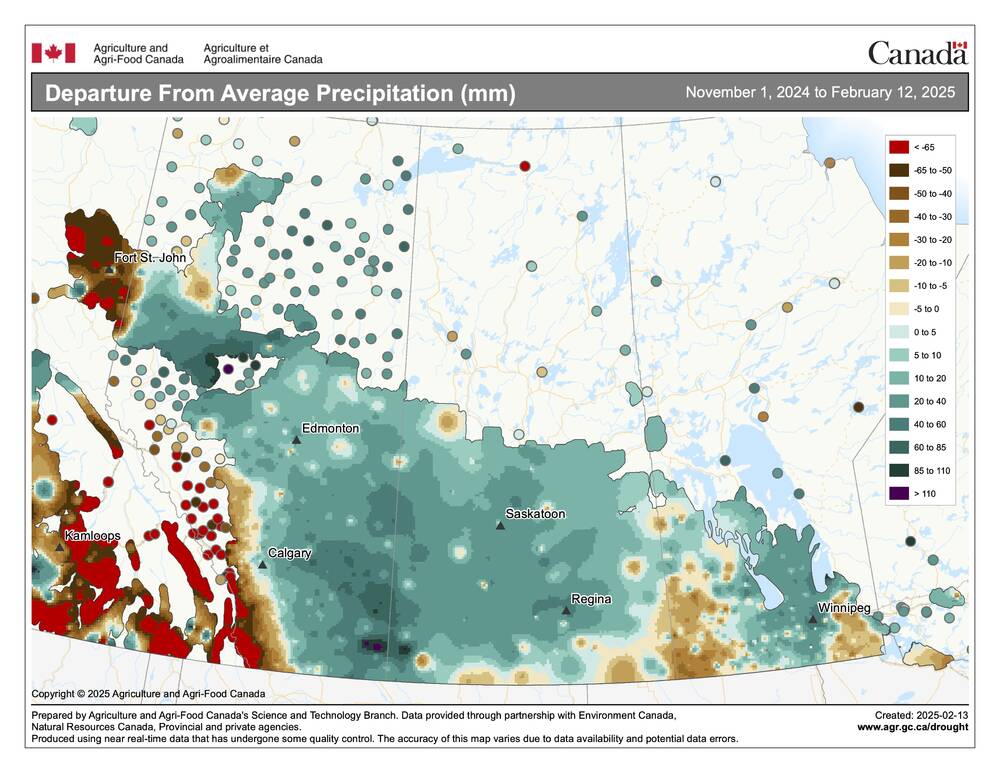

While local areas may feel short of snow, the vast majority of the Prairies has seen above average precipitation so far this winter. Part of the reason for this disconnect is that some of early winter precipitation came as rain, and several warm spells brought melting that greatly reduced and compacted the snow pack.