Let’s talk about record-breaking temperatures. Not daily records, not records for a city or country, but global temperature records.

You may have seen an article or two about how September shattered the record for warmest month, after the warmest August on record. It looks like 2023 will be the hottest year on record for the planet. Let’s dig a bit deeper.

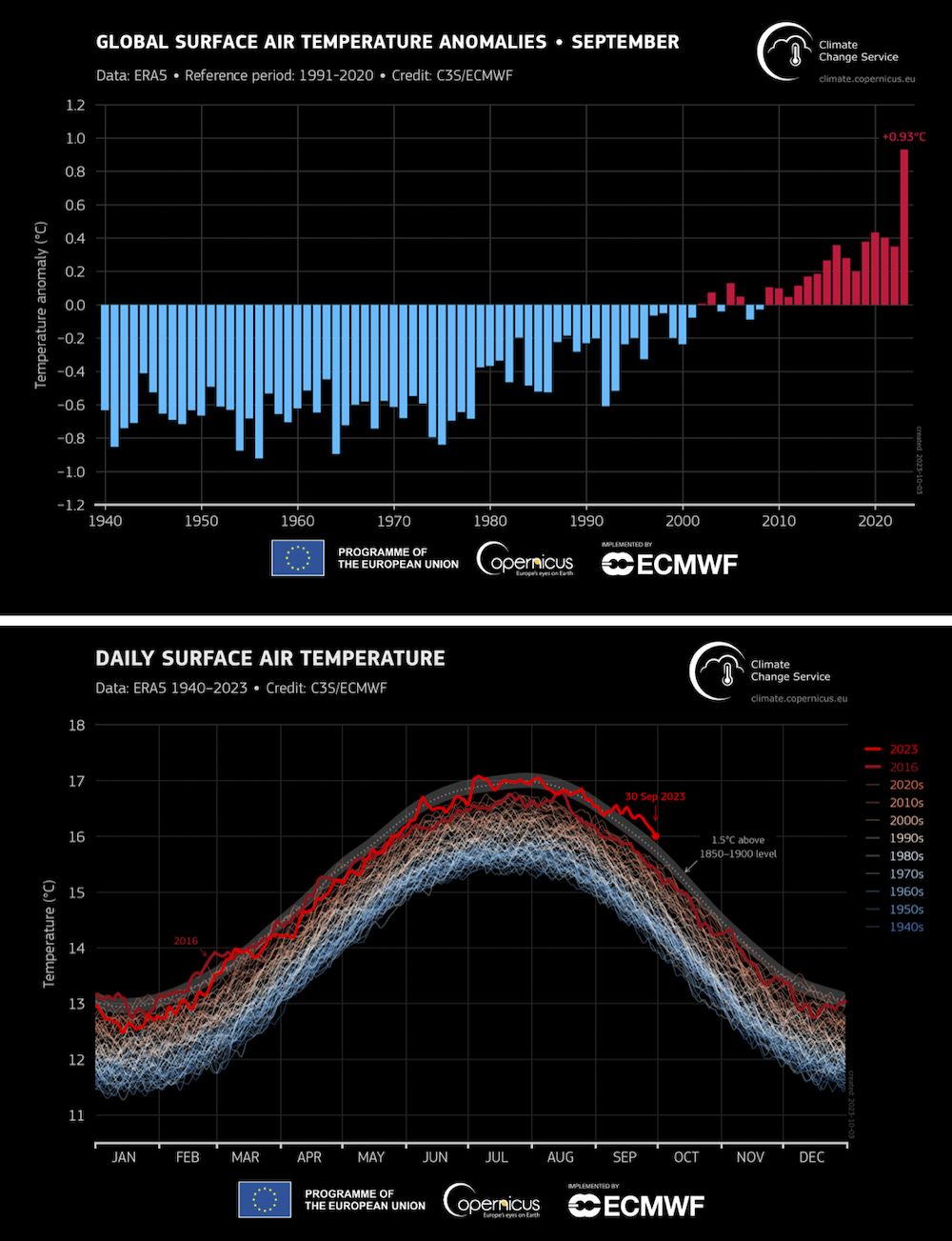

I am using data provided by Copernicus Earth Observation Programme and Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) of the European Union, implemented by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, an independent intergovernmental organization and one of the providers of medium- to long-range weather forecasts in our monthly weather outlooks.

Read Also

Prairie weather all starts with the sun

The sun’s radiation comes to us in many forms, some of which are harmful to organic life while others are completely harmless or even essential, Daniel Bezte writes.

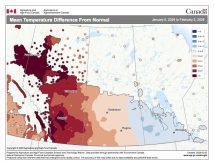

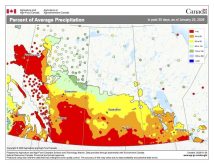

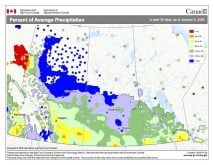

Globally, September had an average surface air temperature of 16.38 C, which was 0.93 C above the 1991-2020 average for September and 0.5 C above the temperature of the previous warmest September back in 2020 (see charts below).

Breaking any record by 0.5 C is huge when it is a city or country record; it is almost unheard of to break a global record by this much. Usually, these records are broken by a few 100ths to maybe a 10th of a degree.

According to C3S, September’s global temperature was the most unusually warm month of any year in its dataset, which goes back to 1940. The month as a whole was around 1.75 C warmer than the September average for the preindustrial reference period of 1850-1900.

August was also the warmest month on record globally, smashing the record by 1.25 C above the 20th century average. All the major reporting agencies (NOAA, NASA, Japan Meteorological Agency, Copernicus) reported similar global temperatures in August.

The global temperature for January-September 2023 was 0.52 C higher than the 1991-2020 average, and 0.05 C higher than the equivalent period in the warmest calendar year, which was 2016.

At the end of August, there was a 93 per cent chance 2023 would be the warmest year on record and those odds have risen since then.

Along with record-breaking surface air temperatures, the planet also saw record-warm ocean temperatures. On July 31, Copernicus reported the average global ocean temperature had broken the previous warmest record and that record was then matched or beaten every day in August.

In September the average sea surface temperature over the oceans from 60 degrees south to 60 degrees north reached 20.92 C, the highest on record for September and the second highest across all months, behind only August 2023.

With all that oceanic heat, and El Nino now becoming a strong event that may last through winter and into spring 2024, I would not be surprised if we continue to see more monthly global temperature records fall.

I also want to look at Arctic and Antarctic sea ice conditions. Antarctica is coming off the Southern Hemisphere winter and its peak growth period for sea ice. After ending the Southern Hemisphere summer with record-low minimum extent in February, while ice was growing at average levels, it was clear by May that Antarctic sea ice extent was tracking far below previous daily lows in the satellite record.

By mid-July, the middle of its winter, ice extent stood at more than 2.6 million square kilometres below the 1981-2010 average. By the end of the winter in early September, the Antarctic ice extent reached an annual maximum of 16.96 million square km, 1.03 million below the previous record low set in 1986.

To put that area into perspective, it’s about the size of Ontario. Again, we usually do not see records broken by these large amounts. There is some discussion among scientists that the ice conditions around Antarctica may be heading into a new regime or increasing decline due to warming oceans.

At the North Pole, the summer minimum ice extent was reached Sept. 19, with an annual minimum of 4.93 million square km, the sixth lowest on record even after what was a rather lacklustre melt season. Looking at the amount of ice loss in September since accurate record-keeping began in 1979, there has been a loss of about 3.45 million square km of ice — the equivalent area of all four western provinces plus the Yukon.

Tie all that together and you start to understand how this piece of the global puzzle can impact the warming of the planet.

I don’t like to bring this stuff up but it is becoming our reality and we are going to have to adapt. I looked at articles I wrote 20 years ago on these topics and here are a few clips:

“September 2005, arctic sea ice hits record low of 5.32 million square km.” This year we didn’t even flinch when we hit 4.93 million.

“2004 – Global warming, and evidence to support it. There have only been a couple of record-breaking warm years and they were in the ’80s, so global warming isn’t real.”

Well, since then we have seen nothing but record-breaking years. In fact, the top nine warmest years on record have all occurred in the last nine years. With this year set to be the next warmest or second warmest year on record, all 10 of the record warmest years would have occurred in the last 10 years. Right now, the 10th warmest year on record is 2010.