Farmers in the Assiniboine River basin will soon have access to a new tool designed to help them make predictions about water flow at the field level.

The tool was developed by the hydrologic modelling firm Aquanty, in cooperation with the Manitoba Forage and Grasslands Association, and the two groups showcased the new technology at the Manitoba Association of Watersheds conference earlier this month.

“When it comes to water management, we at MFGA believe we stand a better chance of managing the water if we’re managing the land,” says MFGA executive director Duncan Morrison.

Read Also

Canadian farm milk price changes to reflect growing protein demand

Protein demand is growing, so the provincial boards that set how Canadian dairy farmers are paid are changing how much protein is emphasized in milk pricing.

“But a critical and vital piece to better management is knowledge. And in the case of the MFGA Aquanty Forecasting Tool, it’s knowing what’s in the system, what’s in the aquifer, and how producers and land managers might be able to better manage water matters and build resilience to climatic events over time.”

Why it matters: Better information about water will allow farmers to make better and more informed management decisions on their farms.

Aquanty and the MFGA began working together in 2015. In the following year, the MFGA Aquanty Model project was greenlit with an Agriculture and Agri-food Canada grant.

[RELATED] Provincial water strategy released

“We built up a three-dimensional model to look at the role of land cover, forages and grasslands, soil permeability and wetlands on the behaviour of this large basin,” says Aquanty’s Stephen Frey. He is a senior scientist at Aquanty Inc. and an adjunct assistant research professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Waterloo.

Once completed in 2018, the MFGA Aquanty Model began to pay dividends. It has been used in a number of projects, including a study of the Oak River/Shoal Lake Watershed, where users examined how forages, grasslands and wetlands influenced flood and drought mitigation between 2009 and 2016.

“In this particular study, we showed that if you reverted the landscape back to more of a pre-development condition, you’re reducing the flood peaks during events like 2011 and 2014 by upwards of 20 to 23 per cent,” says Frey.

The next step

In June 2021, a second round of funding was announced to develop Phase 2 of the Aquanty-MFGA partnership: a forecasting tool geared toward farmers. It is built on top of the Phase I model.

“It’s an awesome time to be a numerical modeller,” says Frey. “We’ve got a lot of big data at our fingertips.”

That data allowed Aquanty to evolve the role of the hydrologic model from a scenario analysis tool to a forecasting tool.

“Using those same models we built for Phase I, we can now start combining those models with weather forecasts at a range of different temporal and spatial resolutions,” Frey says.

They are able to combine their model with remote sensing data on things like soil moisture levels and real time groundwater monitoring sensors to set the initial conditions before launching a hydrologic forecast.

[RELATED] Living Labs links research with the farm

“Combining that with insights on how water management infrastructure is maintained during floods and droughts and using cloud computing infrastructure, we can readily construct these models and deliver them via an app to your fingertips,” he says.

Not perfect

Frey acknowledges the model’s limitations as a predictive tool.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty associated with hydrologic modeling, and that has to be recognized.”

The tool is dependent on weather forecasting, which is always fraught with uncertainty.

“We run an ensemble of models with an ensemble of weather forecasts to come up with an ensemble of outputs,” says Frey. “That allows us to bracket the predicted hydrologic conditions across the area of interest with some probability distributions.”

In other words, a click on one of the waterways provides a “mean” forecast, which shows a line that averages the “ensemble of outputs,” but also shows a shaded area that widens as it is asked to predict the future. Those are the “probability distributions” that Frey describes.

However, each watershed has gauging stations, which are fed real-time data that allow users to calibrate forecasting.

“If we’re predicting good flows upstream from a point of interest and good flows downstream from a point of interest against observed data, then we have a pretty good sense of what’s between those two points of known flows.”

The app allows a user to select an area, such as a field, and tie that to remote sensing imagery.

“We’ve integrated a lot of remote sensing to drive the hydrologic modelling in the user interface,” says Frey. “That includes data like the green index for your land cover. So if you want to go in and extract NDVI data and green index data for the last eight or nine years for a specific field, you can do that.”

Getting there

Frey’s presentation at the watershed conference included screen shots and videos of the app at work. But Morrison cautions it’s not quite ready for public release.

“Understand this is not a final project by any stretch, but we are really, really close,” he says. “We’re at a really exciting point right now with this model.”

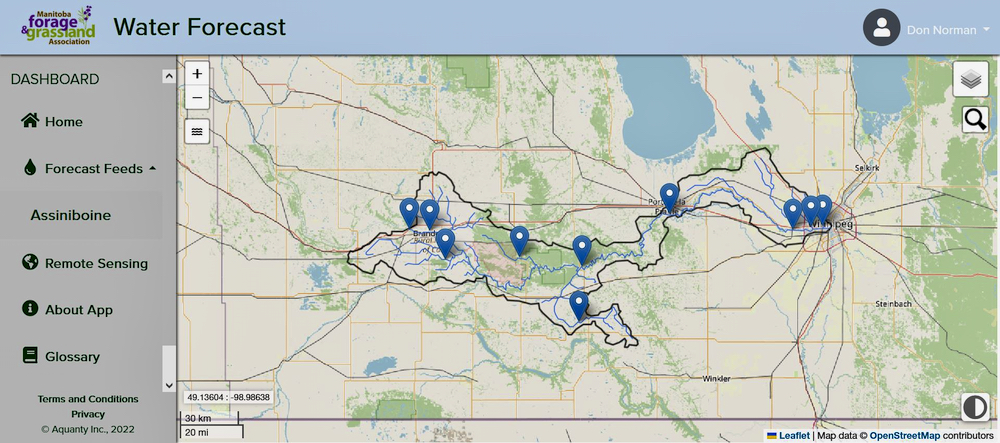

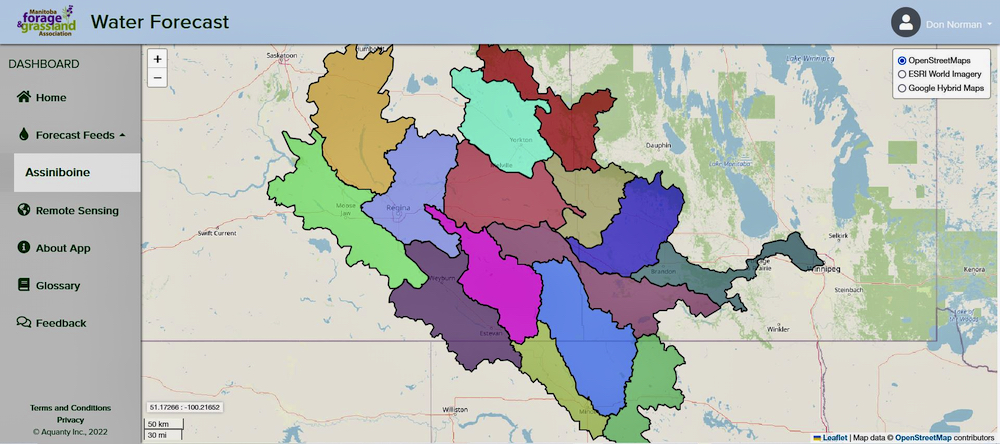

In fact, a beta-test version of the app is available on the MFGA website. The launch page shows a map of the Assiniboine River Basin broken into 15 watersheds. Clicking on a watershed will zoom in on that region. Users can then click on waterways and get a flow forecast.

While the parameters of the forecasting tool will be limited to the Assiniboine River Basin, the technology has potential for use in other areas.

Morrison concurs. In an interview with the in 2021, when the funding for the project was announced, he said he was certain the tech could be used elsewhere.

“We see the work in the Assiniboine River Basin as being transferable, especially with the focus on water,” he said. “We believe that a similar-type modelling system could and should be considered in the Red River Valley and some of the water challenges that producers are affected by there.”