After looking at the latest medium-to-long weather models and checking out the forecasts for the rest of September, I concluded that our monthly weather review and then our look ahead will have to wait until the next issue. Instead, I am going to discuss a topic that was brought up by a reader last week and resonated with me personally.

While I’m not a farmer, I do have some big gardens, and I live in an area with heavy clay soil. My property, while it is flat, is in a bit of a low spot. So if I do get some wet weather it takes a while for things to dry out. If you haven’t guessed it, the topic is understanding the science behind fall drying conditions and why sometimes it can be so hard to get things to dry out.

Weather conditions that define autumn make the work of drying crops more complicated than at any other time of year. Shorter days, cooler temperatures, heavier dews, and less sunlight combine to slow natural drying processes. For crops like corn, soybeans, and hay, this can mean higher costs in fuel for artificial drying, greater risk of spoilage, and the difficult decision of whether to harvest earlier at higher moisture or wait for nature to lend a hand. Understanding the science behind fall drying conditions gives us an edge when making those choices.

Read Also

Can we trust the USDA crop data anymore?

Indications that farmers, analysts and traders have started to lose trust in data from the United States Department of Agriculture are hardly a surprise.

Sunrise, sunset

The most obvious factor is day length. In September, we are losing several minutes of daylight each day. We start the month with about 13.5 hours of day light and by the end of the month it is down to 11.75 hours. Keep going into October and by the end of that month we are down to 9.75 hours. In late June and early July when we have around 16.5 hours of sunlight.

Less sunlight means fewer hours for warmth, evaporation, and wind-driven drying.

Not only is the length of daylight quickly dwindling in the fall, but the sun angle is changing rapidly. In early July at solar noon the sun angle is about 63 degrees. By September it has dropped to 48 degrees, and by the end of October it is down to only 26 degrees. The low the angle the more spread out is the sun’s energy. So, as the days shorten, that natural ability of the atmosphere to dry things out weakens considerably.

This shortening of day length and the reduction in the sun angles leads to our next factor — temperature. As we all know if you have been following my articles, evaporation depends on the difference between the amount of moisture the air can hold and the amount it actually contains.

Warm air can hold far more water vapour than cool air. So in the heat of summer, crops can shed moisture rapidly. By contrast, October days often bring highs of only 10 to 15°C. At those temperatures, the air reaches saturation quickly, and evaporation slows. Even if the relative humidity is not extremely high, the absolute drying potential of the air is simply much lower in fall than in summer.

Moisture in the air

The next factor that often plays one of the biggest roles is humidity, dew and fog. Cool nights can often lead to frequent dew and fog formation. This is often heavy enough to leave fields wet until late morning, or even all day long.

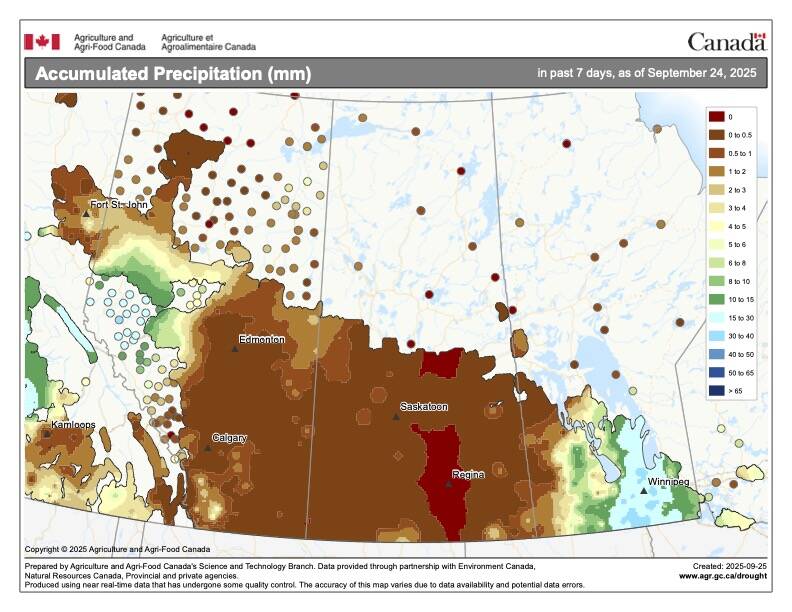

For those of you in central and eastern Manitoba we saw this last week as rainfall brough high humidities. Cool overnight temperatures resulted in heavy dew and fog. Fog not only keeps moisture levels up preventing evaporation, but also reduces the amount of sunshine

There were a few days in a row where grass and crops remained wet each day despite the fact that the sun came out by late morning or early afternoon. Also, high humidity often lingers during autumn due to reduced mixing in the lower atmosphere. These factors come together and result in a much shorter “workable” harvest window compared with the long, dry afternoons of midsummer.

Wind

The next factor is wind, and it often comes hand-in-hand with high humidity and fog. Summer breezes driven by convection are less common in the fall, when cooler air masses stabilize the atmosphere. Without steady winds to carry off water vapour, drying slows further. Calm, damp autumn days can leave crops standing in the field with stubbornly high moisture levels.

The impact of these weather factors is not just academic, as it can almost become a game. Harvest too early and there is the risk of spoilage. Leave it too late and you are exposed to windstorms, lodging, or even early snow — and you still might have to deal with excess moisture and spoilage. On the other hand, harvesting too early means the potential for higher drying costs and storage systems.

In doing a little research, I found that technology has become better for fall drying. Grain dryers, improved storage aeration and better hybrid development all help manage moisture levels. But no technology completely erases the fundamental influence of day length and temperature. Even the best hybrids can only lose so much moisture when the sun is low, the air is cool, and the dew is heavy.

Final word on drying

Tying in our recent look at weather folklore, there are old sayings like “a dry September brings a wet October” or “heavy dews mean good weather ahead” that reflect generations of observation. While folklore cannot replace forecasts, it does capture the lived reality that drying in the fall is about more than just the calendar; it’s about how air, sunlight and water interact in subtle ways. Even today, a farmer’s keen eye for field conditions is as valuable as any chart of average drying rates.

Ultimately, fall crop drying is a story of diminishing returns. Each passing week after the equinox means less natural drying power from the environment, forcing a heavier reliance on mechanical systems. Some years, a stretch of warm, dry October weather saves thousands and makes harvest smooth. Other years, stubborn humidity and early frosts make patience costly.

Either way, the interplay of day length, temperature and moisture is a reminder that, even in an age of advanced equipment, farming remains closely tied to the rhythms of the seasons.

Next issue, September’s weather review and the look ahead at the rest of fall and the start of winter. Possible spoiler, warm weather to continue?