In our annual look at severe summer weather, we have examined what it takes for our summer thundershowers to go from simple garden variety storms to severe storms bringing a type of severe weather.

We examined how hail forms, straight line winds, and then we looked at the different types of whirlwinds with a particular emphasis on tornadoes.

That leaves us with a couple of other severe summer topics: heatwaves and extreme rainfall. In this issue we will start our look at heatwaves, which are actually one of the most dangerous summer weather phenomenons for people.

Read Also

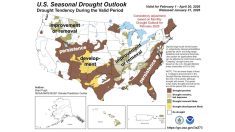

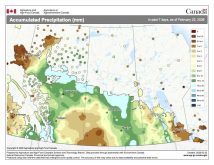

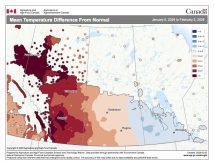

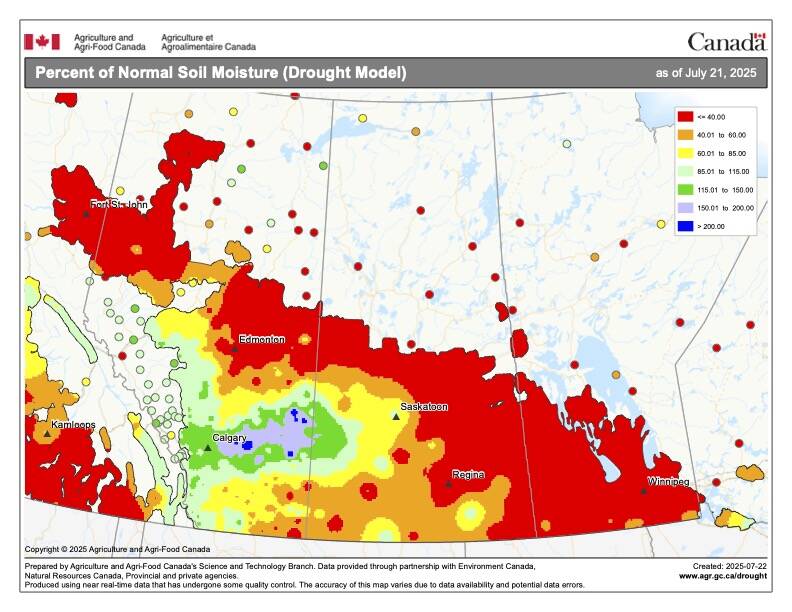

Canada’s farm safety net wasn’t built for this kind of drought

Canada’s business risk management programs were designed as a safety net for one-time shocks. Experts say multi-year droughts are exposing a structural gap — and the fix requires a fundamental shift from paying for losses to preventing them.

Before we dive into this topic, the global July temperature analysis came out a week or so ago. According to NOAA, NASA, European CCCS, and the Japan Meteorological Agency, June 2025 was the third warmest on record behind 2024 and 2023. So far 2025 has been the second warmest year on record to date and they estimate that there is a 95 per cent chance of 2025 coming in as a top four warmest year on record.

Now onto heatwaves. After looking at temperature data so far this summer, while there have been some hot days across all three Prairie provinces, there has not been a sustained heatwave.

To get long lasting heatwaves we need something known as a blocking pattern to develop. Over the years I have discussed this topic usually when we have had to deal with upper-level lows and the blocking patterns associated with these features.

We live in a zone that stretches right around the globe, where warm air moving northwards from the subtropics collides with cold air sagging southwards from the Arctic. When these two different air masses collide, the collision zone can be a battle ground, giving us our constantly changing weather.

Our atmosphere is fluid, that is, it flows, but for most of us it is difficult to picture air flowing. So, picture this; the top of our planet is covered in a heavy substance that we call cold air. This substance wants to run down the planet towards the equator, but instead of simply sliding down in all directions, just parts of it start to sag in large undulations.

Since there is not an infinite amount of this cold air, if some of it sags southwards in one area, other areas will pull northward to replace what has sagged southward. Altogether, at any one time in the northern hemisphere, we have between three and six regions with cold air sagging southwards. Due to the shape and size of these sags, they are referred to as long waves.

Now, what makes this more complicated is the fact that our planet is rotating. To put things very simply, this causes the air to rotate.

Take the picture you have created in your mind of a pile of cold air sitting on the top of our planet with those areas of cold air sagging southward and then have that whole thing start to slowly rotate around the earth.

Now you have a very basic picture of what causes our weather to change from periods of warmth to periods of cold.

When one of the sags of cold air moves across us, we have an outbreak of cold air. When it moves away, we return to warmer conditions. The boundary between the cold and warm air is where the majority of our “weather” or storm systems occur, and this is the typical location of the jet stream (a ribbon of high-speed winds in the upper atmosphere).

We end up having a pattern that repeats itself over and over, stormy weather as cold air moves in, followed by a period of cool or cold weather, then possibly some more stormy weather as the cold air moves off, and finally a period of warm weather. So far this summer this is what we have been seeing.

The next obvious question is, why do we sometimes get the same type of weather for very long periods of time? The quick answer to that is those blocking systems I mentioned earlier.

Blocking is a phenomenon in which this normal movement of weather systems in the atmosphere stops and can lead to prolonged periods of either fine or unsettled weather, depending on the precise location of the block. As long waves develop and move across the globe, certain shapes and patterns of these long waves tend to become very stable and at times can cause the movement of these long waves to stop, preventing other long waves from moving across that region.

The most well-known blocking system is an omega block. It is called that due to its resemblance to the Greek letter omega (Ω). When one occurs, there is usually a large strong area of high pressure, with two areas of low pressure on each side (our long waves).

This particular setup causes the jet stream to flow down and around the bottom of the area of low pressure, then up over the high, and then back down around the low, producing the omega symbol.

Areas that are under the high pressure will see clear skies and warm, dry conditions, while areas under the lows will see unsettled weather with excessive moisture and cool conditions. Typically, these omega blocks will last anywhere from one week up to a month or longer, sometimes forming and then partially breaking down, and then reforming again.

This is the type of pattern that usually brings our intense, long duration summer heatwaves.

The big question as we work our way towards August is whether we will see this type of pattern develop or are we going to see a continuation of our back-and-forth weather? The next few weeks will tell the story as there is some hinting of a blocking pattern developing early in August.

Next issue it is time to take a break from this topic so that we can look back at how July weather compared to average and then look ahead to see what August and September might have in store for us.

We will then finish up our look at heatwaves by examining just how certain conditions can conspire to bring them about.