Economics, investor sentiment and trader psychology are all popular buzzwords that try to explain human nature, but they are nothing new.

They have been around as long as humans, markets and trade have been around. They are all just another way of trying to figure out what the heck is going on. The study of price behaviour over different time periods can help because some patterns do recur. And while it is true that history doesn’t always repeat itself, it often does rhyme.

If long-term market prices are just made up of a series of short and medium-term activity, then getting a sense of what happens over various time frames gives us a clearer picture of where we’ve been and where we might be going.

Read Also

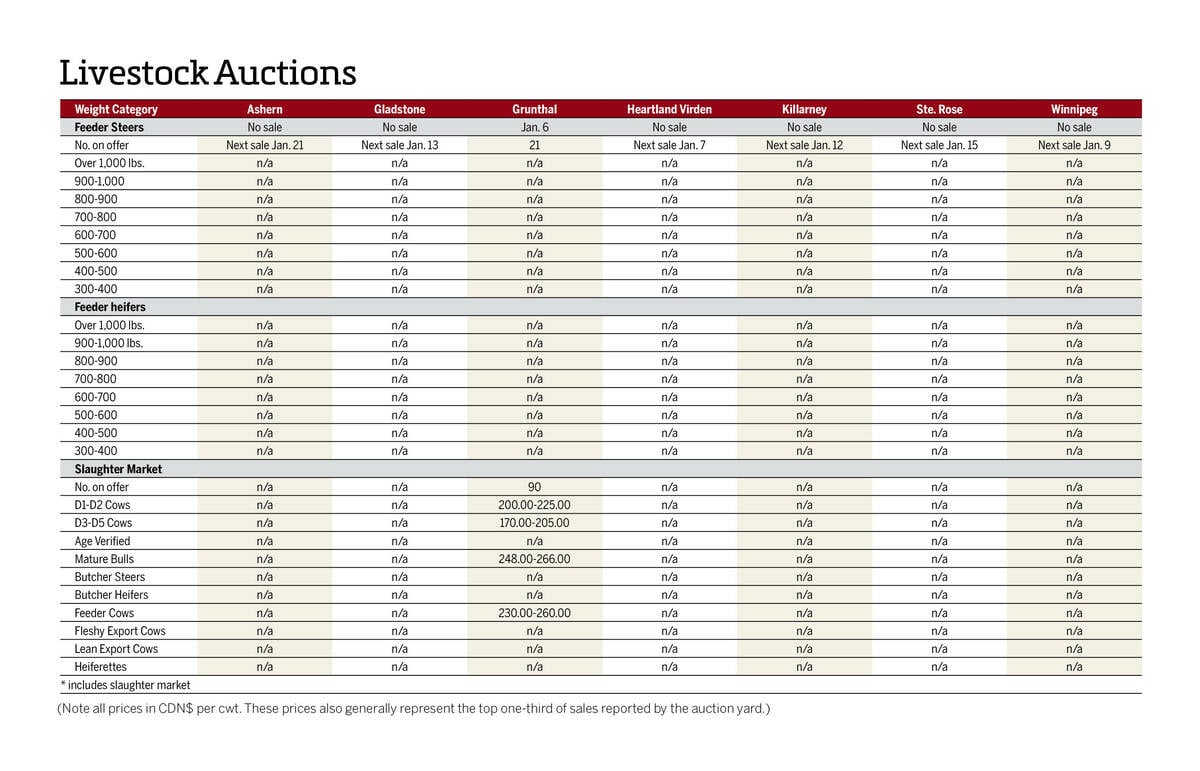

Manitoba cattle prices Jan. 6

Grunthal was the first Manitoba livestock auction mart to kick off 2026 cattle sales in early January.

In the long run, commodity grain prices tend to gravitate toward the lowest cost, most efficient group of producers. But in the short and medium terms, a lot can and will happen to throw prices all over the place. Since history is a guide, not a guarantee, consider this a guide to what grain prices have done, as well as provide some insight and understanding into what they may do over the next several months and years.

[RELATED] Prairie cash wheat: Bids drop with U.S. futures

It is often said that the cure for high prices is … high prices. Following a global disruption caused by war, coordinated government energy or interest rate policy change, or major financial bubble, commodity prices can undergo a dramatic shift higher for months or up to a year or more. As they reach previously unthinkable levels, collective global resources, human ingenuity and profit seeking behaviour are marshalled to deliver that commodity at those high prices. And voila! You have the cure for high prices.

A great example occurred in the early days of the Russia-Ukraine war when European natural gas prices surged dramatically to all-time highs. More recently, however, there were 30 backlogged liquefied natural gas floating storage tankers circling terminals in Spain. There are also potentially dozens more, just waiting to unload their liquid gold since plants are already at maximum capacity. Dutch natural gas futures are now down 70 per cent from their highs in August.

Grain prices were similarly influenced by the panic-induced buying last spring following the Russian invasion, but have since been drifting lower. And while prices may not go back down to the levels of a few years ago, there is still more ground that could be given back.

As for the medium term, we’ve often seen commodities stay in a wide price range for three-to-five-year periods. This can be because of minimum demand requirements, consumer behaviour, available supply capacity, productive infrastructure constraints and government policies.

Canola, corn, wheat and soybean prices were essentially trading in a tight range for five years until the drought last year and then the Russian invasion this year. Canola traded between $400 and $550 per tonne from 2015 until 2020. During that same time, spring wheat futures traded narrowly above US$5/bushel but rarely more than $6.

In fact, we’ve seen this similar pattern numerous times over the past few decades. Will we be entering a new sideway range for grain prices over the next several years? History suggests yes, but history doesn’t always repeat itself.

[RELATED] StatCan data show smaller Canadian canola, durum production

Over the longer term, technological changes, consumer spending habits, social preferences, evolving scientific breakthroughs, environmental and energy policies and buildup of excess production capacity can all combine to sustain a new defined level of commodity prices that can last decades.

It happened following the inflationary and geopolitical triggers of the 1970s that gave way to a new range of prices that lasted more than 30 years. Looking back at history, the impact of the 1972 Soviet grain robbery and high inflation of the 1970s marked a historic turning point in global commodity prices.

Wheat, corn and soybeans, as well as most other commodity prices, never returned to the low levels of the early 1970s – ever. Just as the inflationary 1970s ushered in a new level of higher grain and commodity prices, will the impact of recent droughts, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, pandemic induced food hoarding, low grain inventories and now renewed global inflationary pressures bring about the next step up in the long-term staircase of rising global prices?

Has the world changed so much that we have established a new and possibly higher range of potential prices? Will $700 per tonne be the new floor for canola futures? Or US$8/bu. for wheat futures, $5 corn and $12 soybeans?

Are we entering the next level of grain pricing just like the last time we had major inflation in the 1970s? Are we going back to the future for commodity prices?

Bottom line, will continued high grain prices still be the cure needed to ultimately bring down food inflation? Maybe we are in a very wide and volatile range for agriculture crop prices for the next several years? Or could this just be the beginning of a new long-term pricing environment where the highs of the previous 15 years become floor price levels of support going forward?

There are a lot of questions and not all of them have answers at this time. Since no one knows for sure where prices are going, farm marketing plans with built-in adaptability, including flexible options and futures hedging tools, can help your business thrive in a world full of strange economic behaviour.