Let’s continue our study of clouds by looking at several additional terms that can be used to describe and help identify them, and we’ll also look at some rare or unusual cloud types.

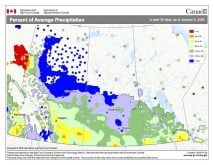

Before diving in, I want to do a quick update on the state of Arctic sea ice, as I have not given an update on this in a while.

According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado Boulder, the yearly minimum occurred on Sept. 18 when the ice extent dropped to 4.87 million square kilometres. This was the 10th- or 11th-lowest amount since satellite records began in 1979. This year was a virtual tie with 2010.

Read Also

Winterkill threat minimal for Northern Hemisphere crops

The recent cold snap in North America has raised the possibility of winterkill damage in the U.S. Hard Red Winter and Soft Red Winter growing regions.

To help put this into perspective, during the 1980s, the sea ice minimum hovered around 6.5 million square km. We are now seeing ice loss in the order of 1.5 million to two million square km, or around a 25 per cent decline. All regions of the Arctic saw below-average ice cover this summer, with the Northern Passage along Russia and both the northern and southern Northwest Passage through Canada opening to potential shipping traffic for at least part of the summer.

Cloud variations

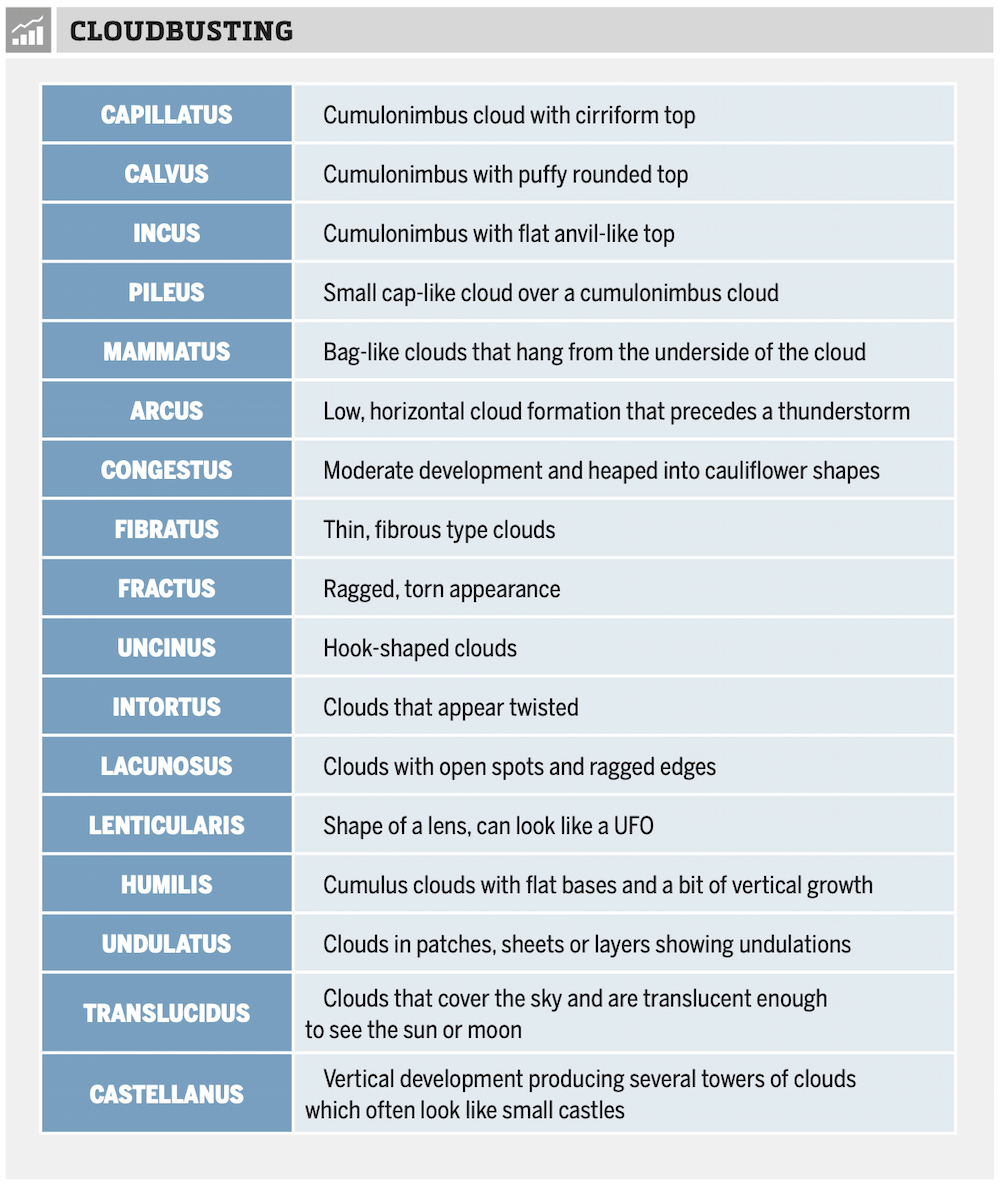

Now back to clouds. Along with our 10 primary cloud types we can add a number of descriptive words to describe the variations. The table here is a list of some (but not all) of these terms.

These descriptive words are usually added to the end of our main cloud type name. For example, if we have stratus clouds that have a ragged or torn appearance, we could call them stratus fractus clouds. If we see several cumulus clouds together growing vertically, we could call them cumulus castellanus clouds.

Some of these cloud descriptor terms may be used on their own. A couple of examples are mammatus clouds, which we occasionally see with thunderstorms, or lenticular clouds, usually seen near mountains.

In the case of mammatus clouds, which can be associated with several of our main cloud types, they should be described technically with the main cloud type first and then the term ‘mammatus’ following (i.e., cumulonimbus mammatus) but most of the time you will simply see them reported or described as mammatus clouds.

Lenticular clouds are named in a similar way. While we should name them as altocumulus lenticularis clouds or cirrus lenticularis, for example, we tend to simply group them altogether as lenticular clouds. One reason is that these cloud types are fairly rare. The lenticular clouds form when a smooth air flow rises over a barrier (like a mountain), which causes a wave to form in the air flow. This is similar to the wave formed when water flows over a rock.

The part of the air stream that is forced upward by the barrier cools and a cloud will form, taking the shape of the wave. Then, as the air sinks back down, it warms and the water in the cloud evaporates and the cloud disappears. This results in a lens-shaped cloud that appears to stand stationary.

Mammatus and lenticular clouds are not the only rare cloud types. We also have nacreous clouds, or what are often called mother-of-pearl clouds. These can be seen in northern countries when the sun is low on the horizon during mid-winter. They are best visible in early dawn or after dusk because they are very high clouds found in the stratosphere (rather than the troposphere), and at these times of the day they reflect sunlight from below the horizon, making them visible.

If you are interested in all the different, unusual and rare cloud types or if you just want to see some cool cloud pictures (along with some other interesting pictures) check out darkroastedblend.com.

I shared this link a few years ago, but it is still a great site for images of extreme and interesting weather phenomena.