A couple of weeks ago we talked about what it takes to form severe thunderstorms: heat, humidity, lift, and some way to vent the air at the top of the storm. This week we’ll take a look at what it takes to make a severe thunderstorm and turn it into a thunderstorm that you just might want to forget ever happened!

Thinking back a couple of weeks, for a thunderstorm to form we need to have a hot, humid air mass in place; the air a few thousand feet up has to be very cold, providing for good lift; and we need a strong jet stream overhead providing the venting at the top of the storm. If we have all of this in place there is good chance we will see a severe thunderstorm. The question is, what can Mother Nature add to the mix to make things even worse?

Read Also

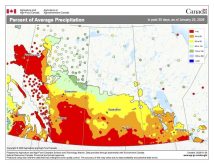

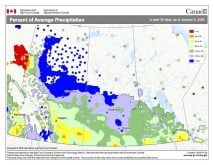

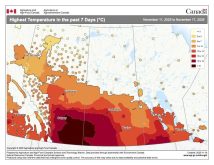

Winterkill threat minimal for Northern Hemisphere crops

The recent cold snap in North America has raised the possibility of winterkill damage in the U.S. Hard Red Winter and Soft Red Winter growing regions.

The first and probably most important “extra” ingredient that can be added is to have a change in wind direction with altitude. Remember that the atmosphere is three dimensional; that is, air can flow horizontally, but this horizontal direction can change as you move upward. Why would this have an impact on our storm?

To put it in a nutshell, this change of direction can cause the developing storm to rotate. Picture what would happen if you take a rising parcel of air and push on it from the south when it is at the surface. Then as it rises up a couple of thousand feet the wind switches direction and now blows from the east. Then a few thousand feet farther up it is blowing from the northwest. What would happen to our rising parcel of air? It would get twisted; it would start to rotate.

Remember, if we can get air to rotate counterclockwise we will have an area of low pressure. As air flows inward in a counterclockwise rotation, it is then forced to move upward. One thing we get if we can get our severe storm rotating is a small-scale area of low pressure and that helps the air to rise even more than it would without the rotation. The second thing a rotating thunderstorm can do is to nicely separate the area of updrafts and downdrafts. This is important, since the downdrafts, even with a severe thunderstorm, will eventually cut the updraft off from its source of warm, moist air. In a rotating thunderstorm, the source of warm, moist air is maintained, giving these storms a long life and a lot of moisture to produce heavy rains. The strong isolated updrafts can also help to produce hail.

Another aspect to the storm that a rotating column of air can provide is tornadoes. While we still do not fully understand how tornadoes are formed, we do know that rotating thunderstorms can produce tornadoes. It is believed that rotating columns of air can get squeezed into a narrower shape; as this happens, the wind speeds increase, eventually producing the tornado.

Like most things in nature, thunderstorms rarely behave like a textbook example. Sometimes, even when all of the ingredients are present, no storms may form, or sometimes a key ingredient is missing, yet we get a really severe storm; this is what makes weather so interesting.

No overhead vent

As we all know, not every thunderstorm that develops becomes severe; in fact, much of our summer rainfall comes from your garden-variety thunderstorm, or what we call air mass thunderstorms. These storms, as the name indicates, develop in the middle of a typical warm summer air mass. Because they are in the middle of an air mass, a number of the key ingredients for severe storms are missing.

Usually, in the middle of an air mass, temperature will not decrease that rapidly with height. The wind will usually remain constant with height, and there will probably not be a jet stream overhead. Nonetheless, we can still have enough heat and humidity for air to rise and thunderstorms will form. Since these storms don’t rotate or have any way to vent the rising air from the top of the storm, they rarely last long. The accumulating air at the top of the storm will eventually fall back down as a downdraft; this tends to wipe out the updraft, essentially killing the storm. The whole process from the start of the storm to the downdraft killing it can be anywhere from 30 minutes to one hour.

While these storms are short lived they can provide brief periods of heavy rain and the occasional strong gust of wind, especially when the downdraft first hits the ground. These storms often provide us with just the right amount of precipitation just when we needed it during the summer. Next time we’ll continue our look at thunderstorms and what is arguably the most costly summer severe weather event: hail.