Winter storms can easily become billion-dollar disasters as the snow piles up on highways and, in the most extreme examples, collapses roofs and power lines. Yet while cancelled flights and business interruptions can’t be avoided, what turns a snowstorm into a disaster often can be.

I have worked for three decades on engineering strategies to enhance disaster resilience and recently wrote a book, “The Blessings of Disaster,” about the gambles humans take with disaster risk. Snowstorms stand out for how preventable much of the damage really is.

The easiest storm costs to avoid involve human behaviour, including driving during snowstorms.

Read Also

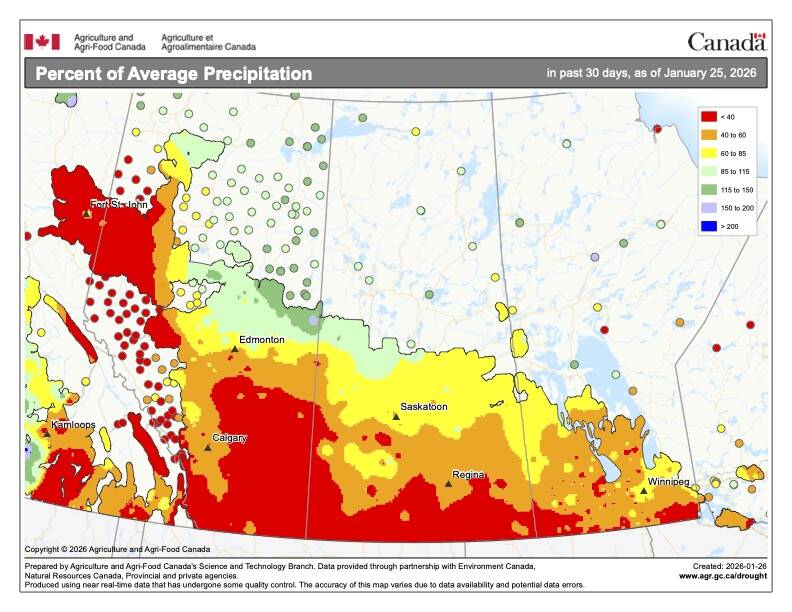

What’s the weather for last half of winter 2025-2026?

A last look at 2025 temperature and precipitation on the Prairies, plus what weather forecasters expect through to spring 2026.

Successfully plowing the snow off a highway requires repeated passes to prevent snow from accumulating. However, that simple concept breaks down when an accident blocks the lanes, and traffic — including commerce and emergency vehicles — grinds to a halt.

When it takes snowmobiles to reach stranded drivers, the wait can be long and in some cases, lethal. Hundreds of people were stranded for up to 24 hours on Interstate 95 during a snowstorm in Virginia in 2022.

Unfortunately, partly due to economic pressures, many people won’t stay home during a blizzard unless authorities close the roads or impose driving bans. Those who venture out should be prepared to survive hours in the cold and have proper gear.

One snowflake at a time, wet snow can pile up to a weight of 30 pounds per cubic foot on a rooftop — enough to collapse a structure that is too light or not well designed. Although roof collapses are relatively rare, they are expensive and can take months to repair.

How snow builds up on a roof depends on a variety of factors, including the height of the accumulation and whether anything prevents it from blowing or sliding away.

Building codes specify the minimum snow weight that roofs must be able to handle to be safe. These have been updated over decades to minimize the risk of structural failure, and they are still improving. Better building codes help improve new construction, but older homes and buildings may still be at risk of a possible roof collapse during a heavy snowstorm.

Homeowners and business owners have a few options. They can invest in an engineering assessment of the existing roof and then strengthen the roof if needed. They can have a team on standby to shovel snow off the roof, which can be dangerous and a major undertaking for the flat roofs of large warehouse and industrial facilities. Or, they can gamble on insurance covering the full cost of repairs is something does happen.

But when it comes to infrastructure failure during snowstorms, power outages can be the biggest problem.

In 1998, an ice storm dumped freezing rain and drizzle for more than 80 hours on parts of eastern Canada and the Northeastern United States. As ice accumulated to as much as three to four inches near Montreal, the weight snapped tree branches, caused power lines to collapse and crumpled hundreds of transmission towers, leaving more than three million people without power for several days in early January. In large parts of Montreal’s South Shore, 150,000 people were without power for up to three weeks following the storm.

Nearly everything today depends on reliable power – infrastructure systems, companies, vehicles and, yes, agriculture. When the power failed during the 1998 storm, heating and ventilation systems stopped working. Pipes burst. Farm animals froze to death or died of asphyxiation by the thousands.

Winter storm Uri in 2021 was even more destructive. It knocked out power in Texas and froze several other states, causing about US$30 billion in losses. Only about half of that was insured.

Many industry sectors depend on the existing power infrastructure and operate without redundancy that could keep them running when the power goes out. While these optimized systems are slim, efficient and cost-effective — all good things under normal operating conditions — they are not resilient. Resilience, which is the ability to withstand or to recover quickly from extreme events, benefits from having a Plan B ready to deploy.

Power utilities may get trees trimmed to minimize the risk of storms bringing branches down on power lines, and some are burying power lines, but power outages are still expected. Businesses and homeowners having a Plan B — such as backup generators, operated safely to avoid creating other deadly hazards such as fires and carbon monoxide poisoning — can minimize the risk of costly losses during a snowstorm or ice storm.

In short, staying off the roads when possible, under a roof that can handle the snow loads and being well prepared for what could be long power outages would help make snowstorms a day off rather than a disaster.

– Michel Bruneau is a SUNY Distinguished Professor in the Department of Civil, Structural and Environmental Engineering School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at the University at Buffalo. This article first appeared in the Conversation, by Reuters.