Employers — including many agricultural employers — seem to have fallen for the trope that ‘nobody wants to work anymore.’

It’s a handy way to back away from any personal responsibility for the industry’s labour woes and one that conveniently avoids looking in the mirror for the source of the problem.

We’ll start by looking at one number that throws this assumption immediately into doubt: the nation’s unemployment rate.

It currently sits at a record-low 4.9 per cent. From a statistical analysis viewpoint, those wiser in economic ways than the average armchair economist say that anything below five to six per cent unemployment is considered ‘full employment.’

Read Also

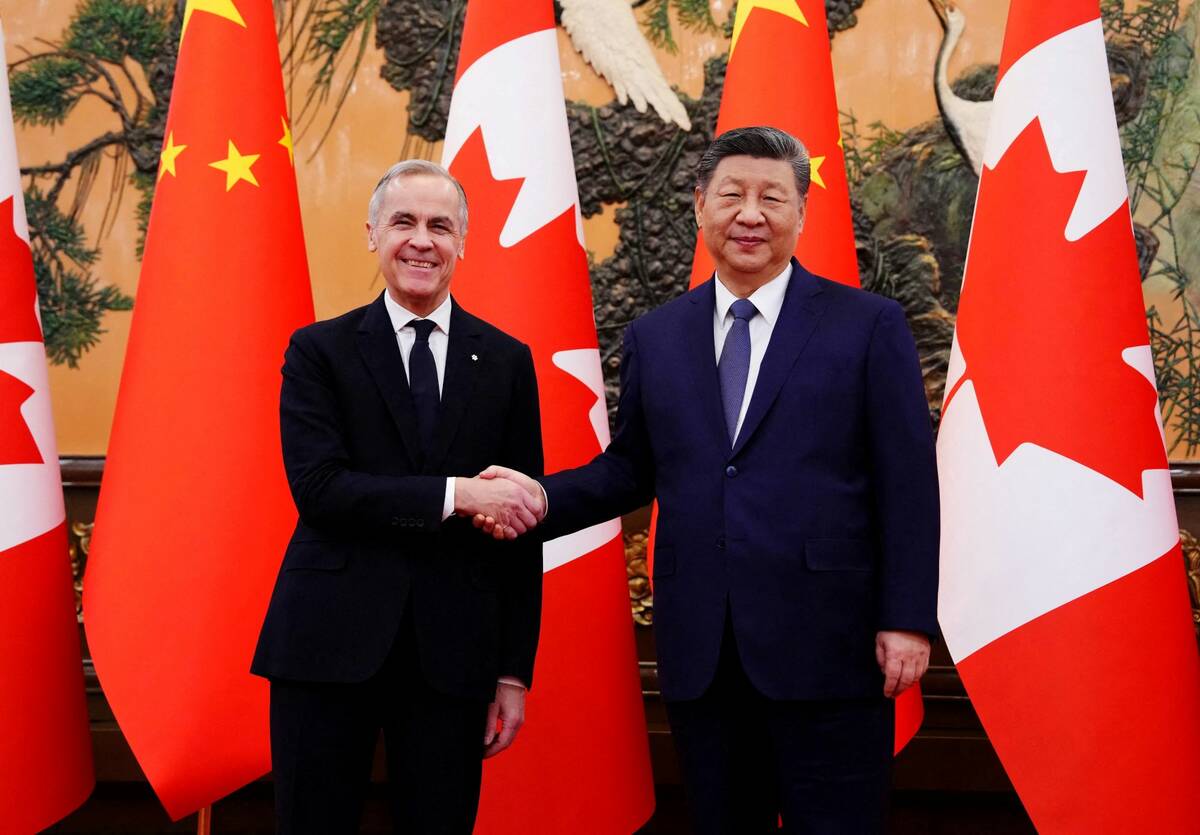

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China is a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

There are more jobs on offer than job applicants in the pool of those without jobs. That figure, by the way, is the lowest it’s ever been since Canada began collecting this data in the 1960s.

The labour participation rate — basically the proportion of the Canadian population in the labour force — remains within a traditional statistical range. The latest figures, from 2021, when the pandemic was still raging, was 62.74 per cent. That compares to a 2018 level of 63.34 per cent.

A 0.6 per cent drop in labour force participation is hardly a crisis and probably reflects the growing rate of boomer retirements more than anything.

To provide further statistical analysis, those participation figures, all from Statistics Canada, have been far lower in the past. In 1997, labour force participation was 61.46 per cent, for example.

So, claiming that a government program, which was in place for a few months and wound down quite a while ago, is the source of employer woe is a pat but incorrect analysis.

Reporters James Snell and Geralyn Wichers delve into this topic in our cover story and they found a very different picture. Of particular interest are the insights of Jesse Hajer, a professor of labour and economics at the University of Manitoba.

Hajer says what’s happened is a structural shift in the employment market. As our birthrate falls, we’re not producing enough future employees here. So we’ve become reliant — over-reliant some would say — on immigration to fill that shortfall. And the pandemic revealed the fundamental weakness of that strategy by slamming the door shut.

As future retirements pick up speed, and more jobs become skilled, it’s logical to think this problem isn’t going away any time soon.

Of course, a future recession might blunt the impact of the trend in the short term, but essentially, things have changed. After decades of the employment market favouring employers, workers have gained some power back.

And here’s where employers are starting to feel some of the adverse effects, as the market imposes its remorseless discipline. As a result, employees are increasingly acting in their own best interests, seeking larger pay packets and better working conditions.

The foodservice industry has felt this most keenly, as restaurants have struggled to staff to adequate levels. Likewise, some retailers, including Canada’s largest drugstore chain, have been forced to cut operating hours because of a shortage of cashiers, stockers and pharmacists.

It’s a bit hard to feel much sympathy for these sectors, whose idea of labour relations, for many years, could be summed up as “If you don’t like it, there’s the door.”

Now that employees have taken up this generous offer, employers are willing to try anything to get workers back. Except, it would seem, increase pay and improve working conditions.

Against this backdrop, the lot of Canada’s farms is even more challenging. The sector was already facing a structural shortfall of workers and struggled to be a place workers should want to build a career. Up the food chain, that has improved, and the growing cadre of agronomists and other professionals demonstrates that.

But a bit further down the line, at the barn, field and even factory level, that picture grows much dimmer. It’s unsurprising. At the farm level, jobs are seasonal, challenging and sometimes unpleasant. And despite protestations that the sector pays “good wages,” the fact that potential employees are choosing other career paths suggests the sweet spot is elusive.

The use of temporary foreign workers will only go so far toward papering over this problem, and as regular readers of this page have been reminded in the past, it’s a risky strategy. Dependent on political goodwill in multiple jurisdictions, it could potentially take one lousy actor and one media blow-up to derail this strategy.

The labour question for Canadian farms is a complex one. Simplistic tropes like “nobody wants to work anymore” does nothing constructive to untangle it.