If farmers think the weather was erratic this year, data says they’re right.

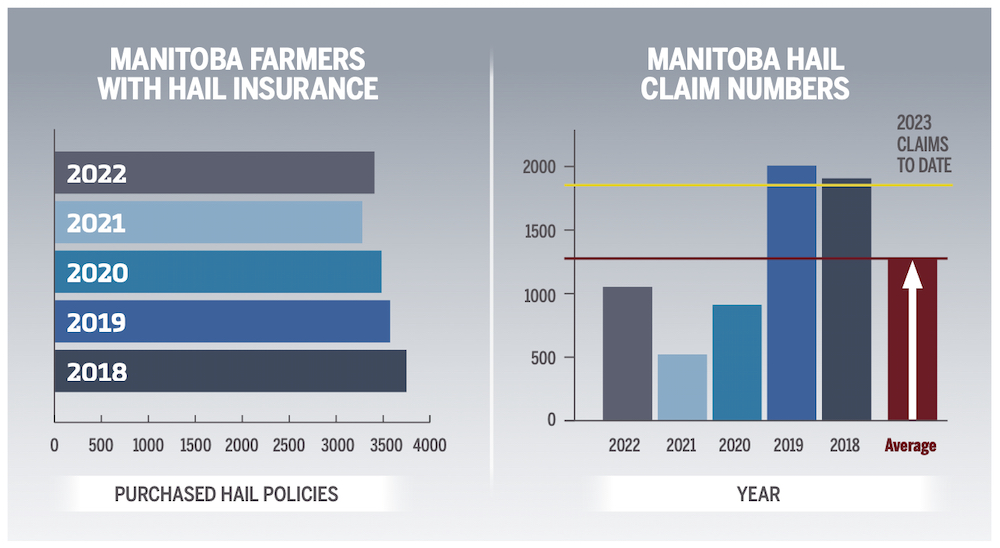

Earlier this summer, the Co-operator reported that farmers in the Rivers area were pummeled with near-apocalyptic hail. Weeks later, they’d been hit again. At the time, hail claims in Manitoba had already exceeded the total number of claims last year.

Why it matters: Weather is always a popular topic of conversation among farmers and this year, there’s been a lot to talk about.

Read Also

Canadian farm milk price changes to reflect growing protein demand

Protein demand is growing, so the provincial boards that set how Canadian dairy farmers are paid are changing how much protein is emphasized in milk pricing.

Hail numbers have climbed since then.

The “white combine” visited fields again in the penultimate week of August. As of Aug. 28, the Manitoba Agricultural Services Corporation reported 1,830 hail claims, including 174 from the spate of storms just days before. Over the five years before 2023, claims averaged 1,280 a year.

The word from farmers is that rain was patchy. In mid-August, Clayton Harder, who farms the north and east edges of Winnipeg, said he had one field of soybeans that was waist-high at one end and ankle-high at the other because rain only hit one portion of his land this year.

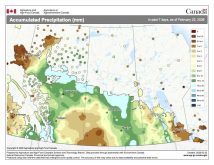

Precipitation patchwork

The volatility isn’t just coffee shop talk. Provincial weather data backs it up.

Of 120 weather stations across Manitoba, all but one had abnormal precipitation levels, said Timi Ojo, the province’s agriculture meteorology specialist.

A scan of the Aug. 27 crop weather report shows rain in the central region ranged from 29 per cent of seasonal normal at Morden to 65 per cent of normal at Austin, “normal” being based on the 30-year average. The southwest ranged from 41 per cent of normal at Findlay to 89 per cent of normal at Newdale.

Eastern Manitoba rainfall ranges from 42 per cent of normal at Gardenton to 93 per cent of normal at Marchand, a 60 kilometre drive away.

For the most part, the province has been dryer than average, Ojo said.

What has fallen has largely been thanks to thunderstorms — deluges that might hit one farm and leave the neighbours high and dry — rather than the widespread, soaking rains across an entire area.

The one station that saw above average rainfall — Fisherton in the Interlake, with 119 per cent of normal — received about 134 millimetres, more than 40 per cent of that rain in one day, said Ojo. Meanwhile, Poplar Field, 25 km south, got only 10 mm of rain on the same day.

“It’s definitely storm-driven and, not only that, it’s been very patchy in the sense that the storms seem to be localized in some areas,” he said.

It’s harder to measure whether there have been more hailstorms than usual, Ojo said. Weather stations don’t specifically measure hail. However, based on other data, such as MASC and Manitoba Public Insurance hail claims, it seems there have been more than the average number of hailstorms, he added.

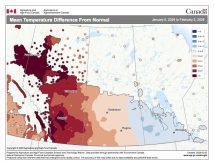

In terms of temperature, provincial data shows it’s been a warm summer but not an absolute scorcher.

Nearly every weather station reported an above-average number of growing degree days. Snowflake, in central Manitoba, saw the fewest number, landing at exactly 100 per cent of normal, while The Pas saw 120 per cent of normal, the highest in the province as of Aug. 27.

Likewise, every weather station saw at least 100 per cent of normal in terms of corn heat units.

Is it climate change?

Climate change has gotten much blame for Canadian weather events this year. In late August, Reuters quoted scientists from Natural Resources Canada, who said wildfires in Quebec had been made twice as likely by climate change.

Fires in Western Canada and the Northwest Territories, flooding in Nova Scotia and ongoing Prairie drought have drawn similar attention.

Pointing the finger at one cause is never simple, although weather experts say a warming planet must be factored in.

“They would occur anyways, but they are amplified in their intensity,” is the phrase used by David Sauchyn, director of the Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative.

Climatologists know the world is warming, but it’s not warming all the time and everywhere at the same rate, said Sauchyn.

From 1948 to 2022, the Canadian average temperature has risen nearly two degrees, according to a 2023 report from Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). That’s based on the annual deviation from a reference value calculated from average temperatures between 1961 and 1990.

However, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and western Ontario have seen little deviation from average. The northern reaches of Canada, in contrast, have seen an average departure upwards of 1.5 C, the ECCC report shows.

On the Prairies, extremes of heat aren’t climbing, Sauchyn said, but minimum temperatures are rising. Summer and fall are getting longer, while spring is arriving earlier.

So, while drought is naturally occurring, more warm days means more days for water to evaporate, potentially making dry conditions worse, said Sauchyn.

Across the globe, most of the warming is occurring in the oceans, he said. Since most weather on the Prairies comes from the west, most local precipitation comes from the warming Pacific Ocean. The Prairies also get moisture-laden air from the Gulf of Mexico, wrote meteorologist Daniel Bezte in an Aug. 24 Co-operator report.

Warmer oceans produce more water vapour, and more humid air masses lead to heavier rain events.

“The two conditions almost always present for extreme rainfall are plenty of moisture and slow movement of systems,” Bezte wrote in another Aug. 30 article. “With current changes in our atmosphere due to a warming planet, these two conditions look to become more prevalent.”

A warmer ocean is leading to more available atmospheric moisture and a warmer atmosphere, if dry, will pull more moisture from a region and lead to even drier conditions.

Bezte also noted that, as ECCC data indicated. the earth’s poles are warming faster than its middle. This lessens the temperature gradient between the two regions, and that gradient is the driving force behind most atmospheric circulations like the jet stream.

There’s evidence that a warming planet will lead to a slowing of weather systems, which could mean longer periods of warm, dry or cool, wet weather, Bezte wrote.

What about hail?

Hail is harder to predict.

“The key ingredient for hail formation is plenty of cold air aloft that is not too high off the ground,” Bezte wrote in another Co-operator report in June. “Most thunderstorms will produce hail. The question is whether it will grow large enough to reach the ground without completely melting.”

That’s why Alberta sees more hail than the rest of Canada, Bezte said. Due to its topography, the freezing atmospheric level may not be that high.

But while intense precipitation is a predicted outcome of climate change, that’s not the case for hail. One of the reasons is sample size, said Sauchyn. Temperature is easy to track and model but by comparison, there are far fewer hailstorms.

Is Manitoba’s bad hail year a product of climate change or is it just weather?

It’s all weather, Sauchyn said, but it’s “weather occurring in a warmer climate.”