It’s been seven years since Brian Pallister stood on the shore of Lake Manitoba and promised that, if elected, channels to divert floodwaters into Lake Winnipeg would be built by the end of his first term.

It was a promise from a party hoping to topple the then-incumbent NDP government, which had been faced with major flood disasters in the previous five years and promised improvements at the north end of Lake Manitoba.

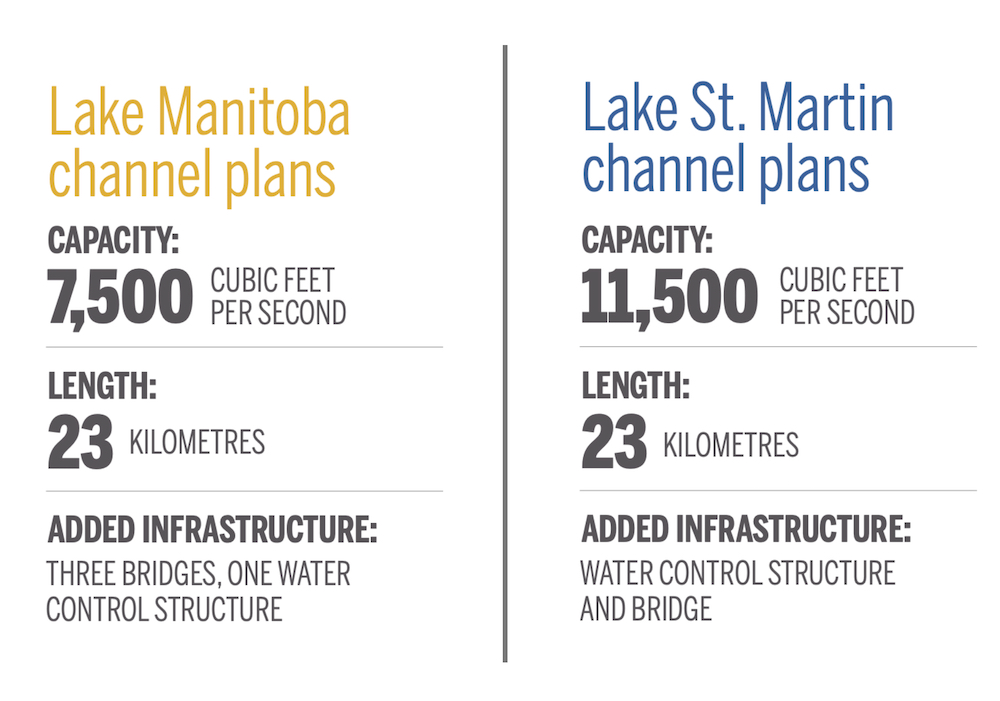

There were calls for two channels, one running from Lake Manitoba to Lake St. Martin and an expanded replacement to the emergency channel dug between Lake St. Martin and Lake Winnipeg. However, the project had been mired with delays.

Read Also

Potato growers beware new PVY strains

Newer strains of potato virus Y (PVY) are creating headaches for potato farms in Eastern Canada, and Manitoba farmers should pay attention

Why it matters: The channel project has lingered in the political periphery for more than a decade, stymied by delays, regulatory hurdles, accusations of inadequate consultation and other issues.

In 2016, as the channel project languished and Manitoba ramped up for a spring election, Pallister adopted the issue for his campaign.

“The NDP’s made promises about this outlet for years and years and they haven’t built it. Our commitment is to build it. That’s the difference between the two parties,” one CBC article quoted Pallister as saying at the time.

The PCs won the election and added a second term in 2019.

Now, in 2023, the Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin channel project remains incomplete.

The project has been stalled since 2019, when an environmental assessment failed to satisfy federal regulators. Additionally, in 2022, a judge ruled that the province failed to adequately consult with First Nations in the affected area.

The province is due this spring to deliver more information to the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, the body responsible for giving the project an environmental stamp of approval, a spokesperson told the Co-operator in an email March 15.

“The province is continuously working on engagement and consultation activities,” they said.

No timeline was given for when the project might proceed.

The main catalyst for the channels came after the 2011 flood. A wet 2010 and snowy winter were followed by heavy spring and summer rains, and water threatened to breach the dike along the Assiniboine River near Portage la Prairie.

Between April 1 and Aug. 5, the province drained 4.7 million acre feet of water into Lake Manitoba, pushing the lake beyond its boundaries.

Three million acres of farmland were submerged. Thousands of people were forced to evacuate their homes. A later assessment put damage from the flood at more than $1 billion.

In early summer 2012, a letter by then Cereals Canada president Cam Dahl described the view of pastures and hayfields around Lake Manitoba as “akin to a visit to [an] alien landscape. Thousands of acres are still under water.”

“What plan is in place to ensure an adequate outlet from Lake Manitoba?” Dahl asked.

Ideas for the project, or something like it, later made their way into the final report of the 2011 Flood Review Task Force and the work of the Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin Regulation Review Committee.

In 2013, then-premier Greg Selinger announced the two outlet channels. The price tag: $250 million. Estimated start date: sometime in 2016.

Opinions on the project varied. Many farmers along Lake Manitoba’s south and west shores advocated for the outlets, calling them necessary for flood management. To the north, farmers in the path of the proposed drains faced land expropriation and major uncertainty as plans dragged on.

When election season rolled around in spring 2016, there was little indication that construction was about to start.

In a March 2016 report, CBC quoted a provincial spokesperson as saying the project was “still in the developmental stage” and construction targets couldn’t be estimated.

Failure to launch

In June 2018, Pallister — now premier — returned to the shores of Lake Manitoba to announce a $540 million, federal-provincial building agreement. By that November, engineering firms had been chosen and CBC reported that construction could begin as early as fall 2019, though no estimated completion date was announced.

However, an environmental assessment of the project, developed by engineering firm Stantec, failed to pass federal regulators’ muster. According to a later article from the Winnipeg Free Press, the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada sent back 27 pages of issues.

It appears the province and the IAAC have been hashing it out ever since.

In 2019, the province also issued a permit for a right of way on Crown land so engineers could monitor groundwater but, as a judge would rule in 2022, didn’t properly consult affected First Nations.

In late 2019 and early 2020, the province crept forward with land expropriation. That caused anxiety among area landowners, some of whom found their farms bisected by the planned channels.

By and large, however, the project ground to a halt.

Dodged bullets

For some, the current roadblocks aren’t all bad. The R.M. of Grahamdale, which will be split in half by the flood outlet, has lingering concerns about the province’s plans.

It is worried that construction will disrupt ground water, according to Reeve Craig Howse. He said current plans involve depressurizing the aquifer, which could cause local wells to lose artesian pressure.

There are also concerns that the channel will draw water out of the surrounding area, destroying wetlands, Howse said. There are further worries about how fish and fishing could be affected.

Delay has given time for more studies, Howse said, and he’s glad for that. However, farmers along the lake remain vulnerable to flooding.

Multiple dry years have kept that bill from coming due, a trend that may hold true again this year, according to the latest provincial flood forecast. A March report from the province’s Hydrologic Forecast Centre shows below normal water levels on Lake Manitoba.

The lake is expected to stay in its normal operating range after spring runoff, barring major weather changes before or during the melt. Water in Lake St. Martin, however, is high.

“We’re at the mercy of Mother Nature and good planning by government,” said Arnthor Jonasson, reeve of the R.M. of West Interlake, which is south of the channel site.

The wheel turns

Manitoba finds itself once again in the spring of an election year, with the official opposition again pointing to lack of movement on the channel project by the governing administration.

“The province has not been doing any work to move the ball forward,” NDP leader Wab Kinew said in March 2023.

The party had issued a release last fall criticizing the Stefanson PC government for the “abandoned” channel project.

“For all the excuse-making you hear from the PC administration in power right now, at the end of the day there’s just a lack of engagement,” Kinew said.

“I think we want to move it forward, but we know in order for it to move forward, it’s got to have everybody involved,” he said. “We’d show up and engage day after day on this file.

“That’s what we’d commit to and that’s how we’d make this thing proceed in a way that the PCs have not.”