Philippe Sabourin’s recently released memoir, Prairie Roots and Wings: Memoirs of Growing Up in the Red River Valley, reads like a love letter to both his Manitoba farming heritage and the wider world that shaped his worldview.

The retired agrologist has a long list of local experience on his resume. He helped build the family seed and export business, Sabourin Seed Service out of St. Jean Baptiste, Man., worked for an agricultural engineering firm and eventually opened his own consultancy. He also has a long list of globe-trotting adventures.

When sitting down to write about those experiences, Sabourin said, he had a few reasons for picking up the pen. He wanted to preserve family history for his grandchildren. He also wanted to share the realities of Prairie farm life in the 1950s and 1960s, and he was advocating for global understanding through what he calls the spirit of ubuntu, a Zulu concept of shared humanity that he became familiar with during his travels.

Read Also

Canadian Cattle Association names Brocklebank CEO

Andrea Brocklebank will take over as chief executive officer of the Canadian Cattle Association effective March 1.

“Primarily, it was for… my grandsons,” he said. “They’re pretty young now, but you know, another five, 10 years from now, or 20 years from now, they can see…how things were.”

WHY IT MATTERS: Philippe Sabourin’s new memoir chronicles a mix of local experience and global perspective.

The 75-year-old author spent more than two years penning the book.

It covers Sabourin’s childhood on a mixed farm near St. Jean Baptiste in southern Manitoba during an era when self-sufficiency was essential. Families grew their own vegetables, butchered their own livestock and preserved food for winter without the luxury of year-round imported produce, he recalled.

“Back then, there were many, many of the farms in southern Manitoba that were mixed farms because we needed the animals and a big garden to survive,” Sabourin said. “The food traveled 100 feet. So that is local.”

His family has a long history in the area. The first Sabourins arrived in the Red River Valley in 1891, and the surname still leaves a mark in the phone books of the region.

Without television in his early years and with no video games, the outdoors became Sabourin’s playground. His recollections include creating a maze by trampling down cattails in a marsh near the family home, fashioning secret rooms amid the reeds where he could lie and look at the sky.

“We had one thing to do, which was to go outside, run, play and enjoy nature,” he said. “We were very privileged to have a big marsh 100 feet from the house.”

Beyond the farmyard

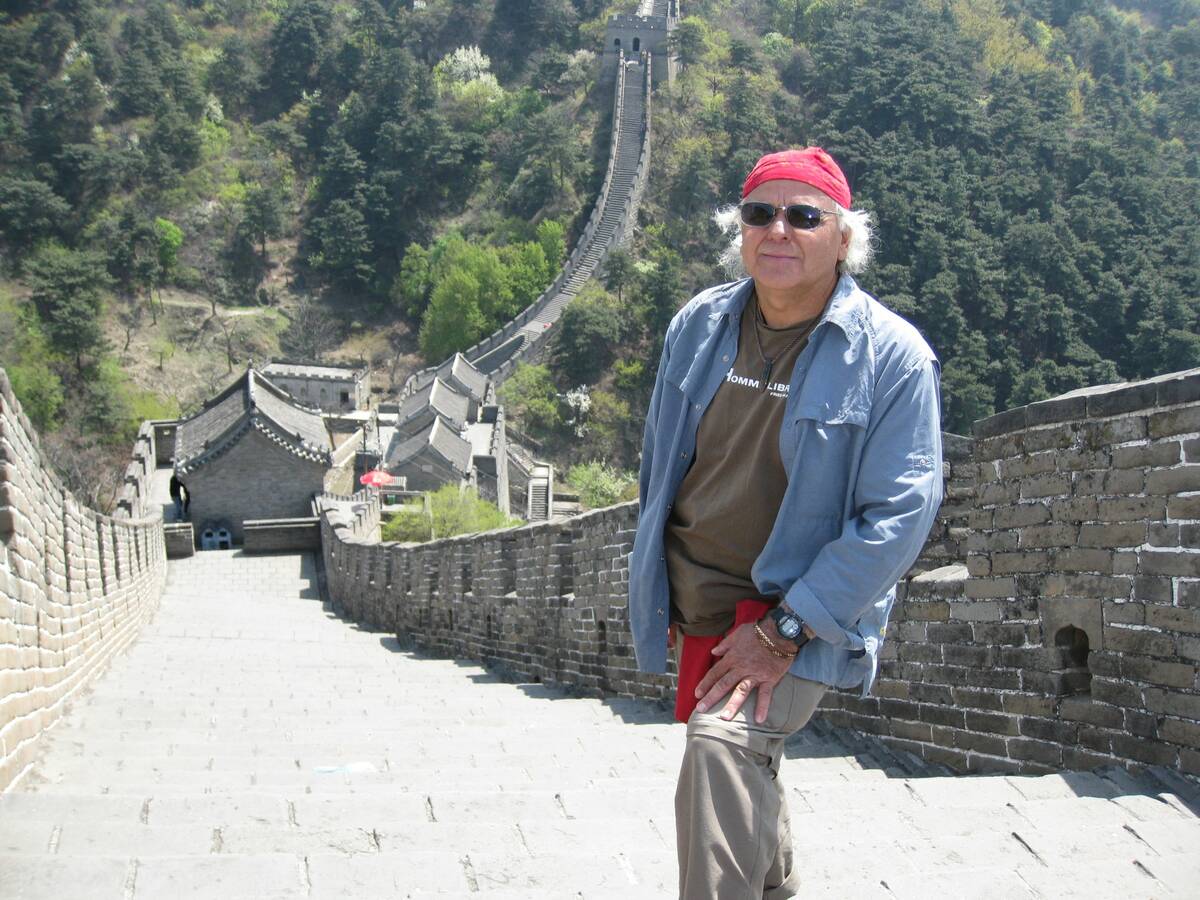

Inspired by his older brother, Gilbert, who took on his own world travels in the late 1960s, Sabourin’s global adventures would eventually take him from the Amazon rain forest in South America to the Serengeti grasslands in Africa, to the Great Barrier Reef, to the Arctic village of Tuktoyaktuk in northern Canada.

His journeys weren’t merely tourist excursions, they were windows into food and agriculture across the world, from Chinese rice terraces to farmers in Bali, at the time still using cattle to pull plows.

In India and Pakistan, he witnessed the massive food distribution systems of Old Delhi’s Naya Bazar, where he captured a poignant photograph of young girls collecting spilled beans from the ground with handmade brooms.

“I saw these kids. Most were young girls, very poorly dressed up, and they had these little handmade brushes like brooms, and they would go and pick by hand or with their broom, with the dirt and grime and manure, and they would bring that back home to eat,” he said.

Those experiences reinforced his belief in humanity’s interconnectedness and the need for empathy across borders.

“All of a sudden, I broke out of that farm and I became a world trekker,” Sabourin said. “We are on a small earth … we all have to help each other.”

Back home, Sabourin built a successful seed business with his brothers, exporting lentils to Europe and bird food across North America, giving him additional perspective on global food production.

“I want to motivate kids and youth…to really think about that and to plan and maybe to save money instead of throwing money away on clothes or frivolous things. Instead, save money and go see the world,” he said.

Despite global challenges to trade and food security, Sabourin maintains an optimistic outlook about humanity’s ability to feed a growing world population through innovation and technology.

“There’s so much doom and gloom right now,” he said. “I’m trying to put a positive spin here, that human ingenuity and scientists and farmers will learn to always improve, and we will be able to feed 10 billion people.”

A lasting legacy

Written in English despite his Francophone heritage, Sabourin’s book also features 150 colour photographs documenting both his Prairie childhood and international travels.

Sabourin recently gifted a copy to the Manitoba Legislative Library, in an effort to make sure his family’s story will be preserved for future generations.

“If somebody picks it up and tries to read what was happening in 1970, it’s there for people to read it and see how we lived,” he said.

Now living in St. Pierre-Jolys, south of Winnipeg, Sabourin continues to plant trees and maintain gardens, though his traveling days may be winding down.

Prairie Roots and Wings is available through Friesen Press as a digital edition and at various rural bookstores.