A trait of regenerative agriculture is that no two farms are the same, but there are five basics behind the philosophy: grazing animals, crop diversity, living roots in the soil, avoidance of bare ground and low soil disturbance.

That last one is a challenge for potato production, since producers need to get under the soil to harvest.

One American spud grower says regenerative agriculture is the tool of choice in his quest to reverse soil degradation.

Read Also

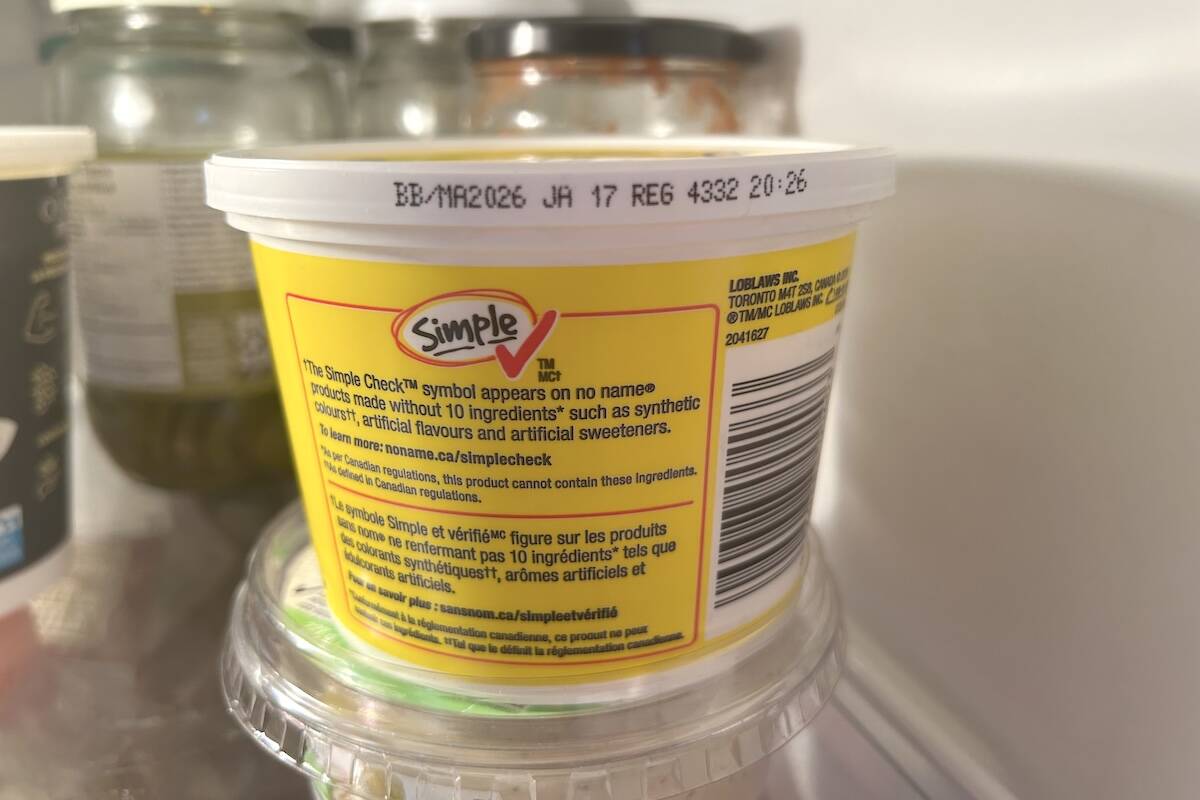

Best before doesn’t mean bad after

Best before dates are not expiry dates, and the confusion often leads to plenty of food waste.

“I’ve been told constantly that potatoes are so hard on the soil; they destroy the soil; there’s no life in soil when you’re growing potatoes. I would disagree,” said Brendon Rockey, operator of Rockey Colorado Farm in Centre, Colo.

Why it matters: The potato sector faces unique hurdles in adopting regenerative ag, but processors are starting to demand it.

Rockey is a third-generation potato farmer. His grandfather started the family operation in 1938. His area is dry, in a region that averages only six inches (just over 152 millimetres) of annual precipitation. In the mid-1970s, consistent water supply issues led the farm to switch to centre-pivot irrigation.

“We had a lot of promises that this was going to make us a lot more efficient with our water,” said Rockey. “But we just became really efficient at depleting our aquifer.”

The farm’s forays into regenerative agriculture started as an effort to plug that proverbial leak.

The movement revolves around farm practices based on soil health and landscape rejuvenation, and soil infiltration and water management are among the touted benefits.

On Rockey’s farm, that required a shift in crop rotation.

His standby potato-barley pattern was contributing to the dwindling aquifer, Rockey said, so he had to get away from barley.

“We started incorporating cover crops. To grow a barley crop, you’re looking at about 22 inches of irrigation. I can do a really nice cover crop off of six to seven.”

The water savings were excellent in the first year, but Rockey also noticed an improvement in the soil’s water retention properties – so much that it also saved him water in his potato crop the following year.

Those early cover crops were monocultures, but after a visit from soil health expert and regenerative agriculture advocate Jay Fuhrer, he was convinced to try multi-species cover crops.

“The following year, when I had my first potato crop, it was probably the biggest leap forward I ever took in one single season,” he said. “I was hooked.”

Progressing regen ag

Rockey has since run the gamut of regenerative agriculture practices. He’s arranged with local livestock producers to graze his land. He’s even come up with a novel method to intercrop peas with his potatoes.

“I’m able to maintain my yields, I’m able to reduce my cost of production, and I’m able to improve the quality of my crop,” said Rockey. “That’s a winning scenario.”

Pests are another area where Rockey has veered from conventional practice. Aphids are his biggest problem because they are disease vectors, so he encourages beneficial insects.

“If you break down all these different practices, there are a few things I think are absolutely essential: cover crops, eliminating synthetic fertilizers, outsourcing your photosynthesis and eliminating toxic chemicals,” said Rockey, referring to fungicides and other pesticides.

“Outsourcing your photosynthesis” refers to things like manure fertilizer, so the producer is not relying solely on in-field gains like root biomass to build soil organic matter.

Instead, energy generation happens on another field, and livestock are the vehicle to import it into the cash crop.

“After you get those established, that’s when you start bringing in some of these other things, like companion crops,” said Rockey. “And if you can bring in grazing on top of those cover crops, you can enhance it a little bit further.”

Manitoba producers face one major pest that Rockey does not: Colorado potato beetle.

That scourge causes serious economic damage on local potato fields. Control has also become trickier due to rising chemical resistance.

Recent work on biopesticides might give producers a non-chemical tool. This summer, the Pest Management Regulatory Agency greenlit trials of a novel RNA-based product that targets the species on a cellular level.

In terms of low or zero tillage, Rockey puts it at the bottom of his list of essential practices, mainly because it’s difficult to do with potatoes.

“I’m always going to have soil disturbance with potatoes. But if I can eliminate a useless pass, I’m absolutely going to do that,” he said.

Processor push

Potato growers in North America face pressure to adopt practices like Rockey’s.

In 2021, McCain Foods announced it would require suppliers to adopt regenerative practices by 2030. PepsiCo, which makes Frito-Lay potato chips, issued a similar statement the same year.

McCain Foods defines regenerative agriculture as “an ecosystem-based approach to farming that aims to improve farmer resilience, yield, and quality by improving soil health, enhancing biodiversity, and reducing the impact of synthetic inputs.”

It has been a hard pill to swallow for some Manitoba potato farmers.

“Farmers do a great job at what they do, and they don’t like to be told what to do; certainly not from people that are not engaged in the day-to-day job of producing the crop,” said Susan Ainsworth, executive director of the Keystone Potato Producers Association.

As a result, Ainsworth said, there has been pushback to the processor announcements.

“There’s been some talk about greenwashing, but I don’t think that’s the case,” she said. “I think their motives are true, and I think they’re trying to build some resilience into their supply chain.”

Both Ainsworth and Rockey, along with Swan Lake-area grower Russell Jonk of Swansfleet Alliance, were part of talks on regenerative potato farming at the Manitoba Forage and Grassland Association Regenerative Ag Conference in Brandon Nov. 13-15.

Local sustainable spuds

A number of local potato producers have undertaken sustainability efforts.

In 2020, Chad Berry of Under the Hill Farms near Cypress River, Man., ran a demonstration trial in partnership with J.R. Simplot Canada to incorporate direct seeding. The goal was to mitigate erosion.

“There’s four to five weeks where the fields are black and powdery,” said Berry in a 2020 interview with the Co-operator. “[If] we can leave some stubble standing, it’s not going to be nearly as bad.”

The trial divided one of Berry’s fields in two. Half was managed conventionally and the other half was direct seeded into canola stubble.

Berry had already upgraded his planters to a one-pass planting, hilling and fertilizer system, inspired by technology he saw at German trade show Agritechnica. He and local equipment company genAg adapted the hillers for a North American machine. The result was Berry’s 34-inch, eight-row Spudnik planter.

The system did not eliminate tillage, but that spring, the direct-seeded half of the field received only one pass.

The results were exactly as hoped. There was no difference in yield on either side of the field, nor were there any statistically significant quality or disease differences. Although the direct-seeded half emerged slightly later, that delay didn’t follow through to harvest timing.

At the same time, direct seeding that year saved fuel, limited topsoil loss and reduced the farm’s emissions for that parcel.

Soil erosion was also the impetus for Jonk to dip his toes in the regenerative ag pool. His farm had noted erosion problems in potato years and often in the following year as well.

“If you’re planting wheat into that bare soil, it’s usually not too much of a problem,” said Jonk. “But if you start growing corn and you don’t have that soil covered, there’s a real potential for some bad erosion.”

Swansfleet, operated by Jonk in conjunction with his father and uncles, farms seed and processing potatoes, as well as a rotation of grain crops covering corn, soybeans, wheat and canola. They’re just started to implement regenerative practices, conference attendees heard.

“We’re still very much in the trial phase of these things, but we’ve seen some benefits and we definitely see the need for some changes,” he said.

One of their early efforts was cover cropping. The farm jumped all-in on the practice, taking a field out of rotation for a full season cover crop.

“We put in an 11-species cover crop mix, and it was beautiful,” he said. “It grew six feet tall. There was sorghum-Sudan grass in there; there were oats, millet, peas, buckwheat and faba beans. It was really a great learning experience. The soil was absolutely more mellow afterwards.”

But taking full-year break for that field was hard to justify economically. They soon turned instead toward shoulder-season cover crops. Those provided soil armour and growing roots during times that would have otherwise have been bare ground.

“We’re doing things a little more intensively on a smaller scale, on a couple of fields, trialling some things, and just proving the concept to ourselves,” Jonk said.

Looking ahead

Uncertainty remains about how McCain’s 2030 regenerative agriculture commitment will affect growers. Ainsworth said that’s a challenge looming for potato farmers who want to continue supplying that processor.

“It sounds like a no-brainer on the surface, but when you really start to dive down, it’s very regionally specific; you have to look at the assets that you have locally and capitalize on those,” she said. “It’s going to take a lot of knowledge sharing back and forth and a lot of trial and error.”

She also said some of the burden must be removed from growers’ shoulders.

“I think we have to look at different cost-sharing mechanisms and ways to get more money into the growers’ pockets to help make that transition.”