There is a low risk of a widespread grasshopper infestation in Manitoba this year, though there are a few areas of concern.

“I don’t want people to let the guard down,” says John Gavloski, Manitoba Agriculture’s entomologist.

“I certainly don’t want to indicate that we’re in an outbreak because I don’t believe that’s necessarily true. At the same time, if we do get conditions that favour the grasshoppers, there’s at least a high probability that there’s going to be areas and fields where levels are high enough that control is needed.”

Read Also

Trade uncertainty, tariffs weigh on Canadian beef sector as market access shifts

Manitoba’s beef cattle producers heard more about the growing uncertainty they face as U.S. tariffs, and shifting trade opportunities, reshape their market.

Control measures were needed last year, he notes.

“We’re still in a cycle where we have seen some building of the grasshopper population. Things could be very similar unless we get some decrease in the population because of weather-related events or natural enemies.”

Why it matters: Grasshopper risk is rising and cultural control methods could help keep it out of ‘outbreak’ territory.

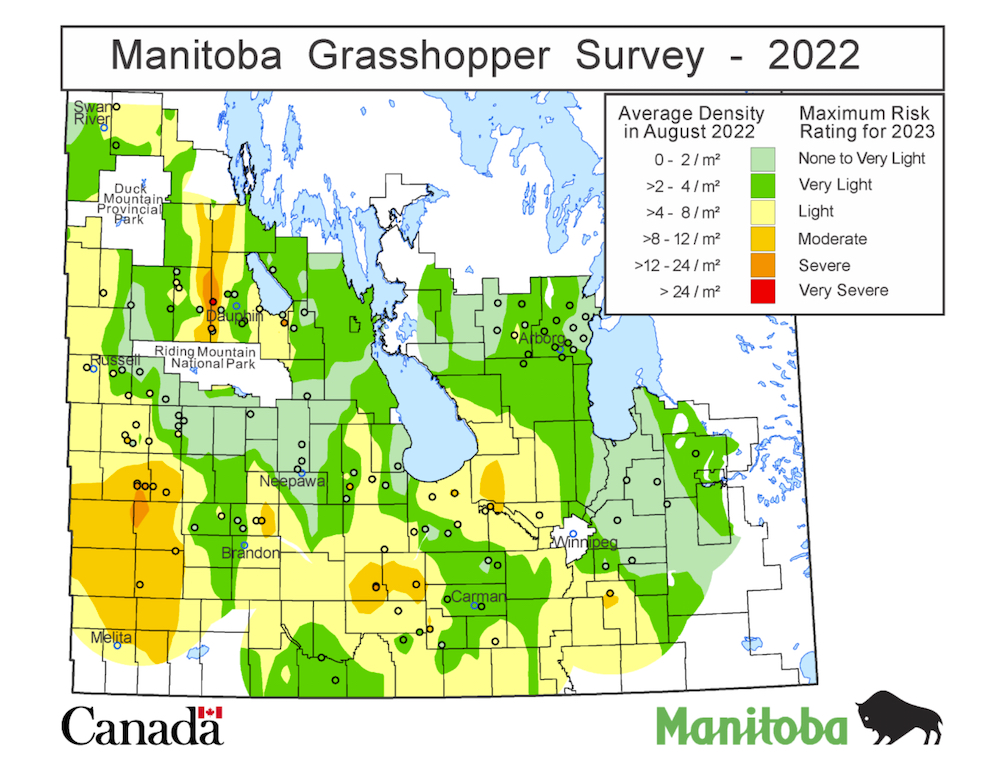

According to the forecast map, those areas appear to be centred in the western portion of the province. The grasshopper forecast is based on insect counts in August, weather data and recent trends.

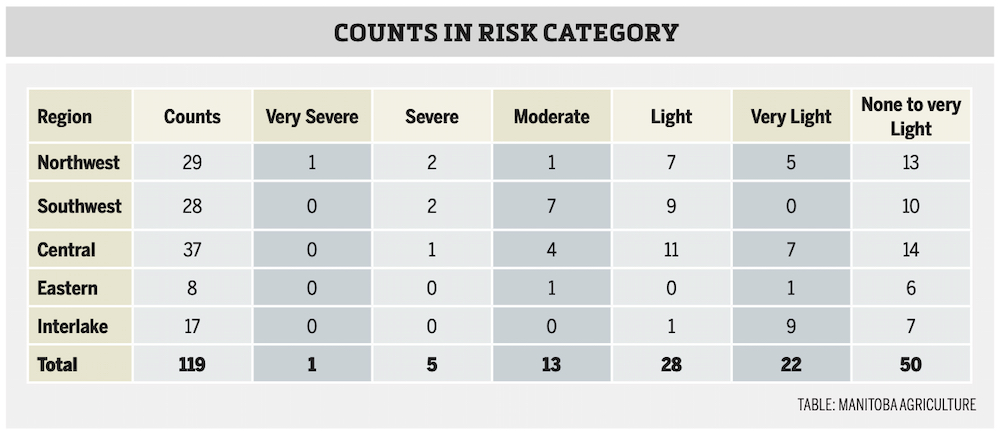

About 60 per cent of the counts were in the very low- or no-risk categories. Roughly one quarter were in the moderate-risk category. Grasshoppers are likely to be the biggest concern in western Manitoba, where five counts were in the severe risk category. One count in the northwest region, near Ashville, was in the very severe risk category.

[RELATED] The year in pest insects on Manitoba fields

The two-striped grasshopper was the most abundant species in 31 of 32 locations across the province. In the central region, the clear-winged grasshopper was dominant.

Rising risk

Grasshopper counts have been on a fairly steady increase since 2018, when the entire map showed very low or no risk. This could mean a more severe outbreak is around the corner. Grasshopper outbreaks usually develop after a few years of conditions favourable for the pests, usually hot and dry.

“Hot-dry can lead to more eggs being laid and potentially fewer pathogens in the population. Especially when you get consecutive years of hot-dry, it does help build the population.”

Everyone remembers last year’s wet spring. Is it possible that moisture has put a damper on the apparent trajectory of grasshopper populations?

Apparently not, says Gavloski.

“One of the misconceptions that is often out there is that if we get a lot of rain in the spring, you will kill the grasshopper eggs. But that won’t happen,” he says. “It’s the nymphs that will get killed by excess moisture. If they’re still in the egg stage, the fields can be flooded for days and the eggs will survive.”

Gavloski says that since the excess moisture occurred early, there wasn’t a lot of nymph mortality.

Even so, that doesn’t mean a severe outbreak is imminent. Moisture isn’t the only downward pressure on grasshopper numbers.

“There are also natural enemies that regulate the population,” says Gavloski. “When the grasshopper populations start getting higher, some of the natural enemy populations — sometimes it takes a year or two — will start building in response to there being more grasshoppers.”

The good news is that he’s seeing some of those natural enemies in the surveys.

“We’re seeing evidence that populations of some of the egg predators have really increased.”

One of those is the blister beetle. Their larvae feed specifically on grasshopper eggs. The grasshopper bee fly larvae also feed exclusively on grasshopper eggs, and Gavloski says he saw many last year.

[RELATED] Weird pest phenomena a boon for farmers

Moisture last spring didn’t do much to kill the nymphs, but Gavloski says there was more summit disease, a fungal ailment that infects grasshoppers in warm, wet conditions.

“The grasshoppers would have been infected early and spent their summer being infected. And we saw the remnants of the dead grasshoppers up on the plants late in the season. One of the outcomes of summit disease is that grasshoppers die while clinging to the tops of plants.”

Managing outbreaks

Gavloski says Manitoba Agriculture encourages farmers and agronomists to spray only when the risk reaches the economic threshold, in order to protect beneficial insects.

“If you’re using a broad-spectrum insecticide, you’re taking out the good with the bad,” he says, but there are options available that selectively kill grasshoppers and don’t affect the beneficials.

“We encourage growers to consider those if it’s practical and affordable, because that will help preserve that natural bio-control.”

With that delicate balance at play, it’s helpful to look at how the organic sector manages grasshoppers.

Martin Entz, professor of Cropping Systems and Natural Systems Agriculture at the University of Manitoba, recently gave a lecture on the subject.

Plant diversity

Entz says pest problems are less likely in a complex farm ecosystem where there is more diversity of plant structure.

“One of those examples is intercropping and cover cropping, which definitely can help reduce insect problems,” he says.

In research Entz did in the early 2000s, he used pitfall traps to trap carabid beetles (who dine on grasshopper eggs), which were sorted and identified.

“In the study that we had, we had three organic systems: a grain only organic system, one that had green manures in the rotation, and one that had alfalfa mixed with grain crops.”

The study concluded that different crop rotations resulted in different beetle populations.

“What was interesting is that the greatest diversity of plant populations resulted in the most diverse and the greatest number of beetles,” says Entz. “So, a diversity of plants means the diversity of these beneficial insects.”

Another benefit of greater plant diversity as it relates to insect control is that it can boost natural resistance.

“Plants actually talk to each other with their volatiles,” explains Entz. “They release chemicals, and those chemicals float in the air, and other plants will respond to them.”

“A neighbouring plant is going to sense those and turn on some of its self-defence mechanisms. It doesn’t absolutely make the plant immune to that insect, but it certainly increases its resistance.”

Entz also points to studies that show population density of plant-eating insects in polyculture fields (like intercropping) is lower than in monoculture fields. In contrast, the population density of natural enemies, especially parasitoids, is found to be lower in monoculture, “so the pest itself is higher in monoculture, while its enemies are lower.”

Push-pull systems

A push-pull system literally pushes away pests and pulls them to another place. For example, grasshoppers do not like certain pea varieties, so peas can be planted as guard strips around more preferred crops, like flax. That’s the push part of the equation.

An example of the “pull” side is perennial strips.

“We put a perennial strip around the field because we know the grasshoppers like to lay their eggs in those perennial planting strips, and then we can till them to kill the eggs or kill the nymphs,” Entz says.

Grazing Systems

Research has shown that in pastures, twice-over grazing systems result in fewer grasshopper outbreaks than season-long grazing.

“The reason for that is that it reduced the quality of the habitat for the grasshopper,” Entz says. “Grasshoppers need to have their temperature regulated, and if you have areas in the field where you’ve got inconsistent temperature regulation, you can make the grasshopper less happy.”

Disturbance

Grasshoppers prefer undisturbed areas to lay their eggs, which is why they often lay them in ditches. As a result, tilling in fall to make it less desirable for egg laying is an age-old practices.

“Of course, there is a trade-off there between soil health,” Entz says. “In the Conservation Reserve Program in Texas, they talked about shredding the perennials so you’re not having to till them.”

Entz suggests mowing ditches could achieve similar results.

“The dead plant material is less attractive to grasshoppers, so anything that increases the disturbance of the soil will reduce the grasshopper.”

Landscape diversity

Many grasshopper species live on the Prairies, but only four are harmful to agriculture.

“Landscape diversity is very important,” says Entz. “Things like wetlands allow the other 180 species of grasshoppers to thrive, and when you have greater diversity, you’re going to have fewer of the pests.”

However, he admits the effectiveness of some grasshopper control techniques is limited if an outbreak gets out of hand.

“The challenge with grasshoppers is that when they get into really high numbers, they move so quickly that some of these strategies may not make that much of a difference.”