The Canadian Foodgrains Bank is asking its supporters to write to federal finance minister Chrystia Freeland and ask her to include more money for international aid in the 2023 budget.

“We want her to know Canadians care about doing more to support small-scale farmers in building climate resilient food systems,” wrote policy advisor Andrew Defor in a Feb. 21 email to supporters.

Hunger has been increasing since 2019 or 2020, said Paul Hagerman, director of public policy at the foodgrains bank. Economic shocks from the pandemic, combined with conflicts throughout the world and the effects of climate change, have increased food insecurity.

Read Also

Canada’s import ban on Avix bird control system ruffles feathers

Canadian producers’ access to Bird Control Group’s Avix laser system remains blocked despite efficacy studies and certifications, as avian flu deaths rise.

The number of people in crisis — meaning those who are selling tools, livestock and land or pulling kids from school in order to make money to buy food — has nearly doubled in the last five years, Hagerman said.

Canada increased international aid funding during the pandemic but Hagerman said it appears that was a one-time bump.

“We’re saying this is not the time to drop back down to old levels,” he told the Co-operator.

“It’s time to take a big step and invest more in food systems that are resilient to climate change, and also food systems that support gender equality.”

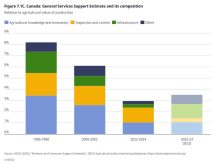

He said the Liberal government has been increasing aid funding, and in 2021 doubled Canada’s commitment to help countries adapt to climate change. However, support for food systems, including agriculture, markets, processing and infrastructure, hasn’t grown.

In a recent visit to projects in Africa, Hagerman said he saw how resilient food systems can make a difference. In Zimbabwe, a multi-year drought prevented farmers from producing enough food so they were reliant on food aid.

Foodgrains bank partners are supporting farmers to implement conservation agriculture principles, and these have led to higher yields for producers. They may still need some food aid, Hagerman said, but the need has lessened.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, many people are affected by conflict. In the eastern region he visited, there are few jobs and many young men have joined armed groups that take resources by force.

A foodgrains bank partner organization is working to convince these men to return to village life and take up farming.

Canada’s aid can reduce poverty and conflict and contribute to peace and stability that ultimately makes the world a better place, Hagerman said.