In 2017, then-provincial agriculture minister Ralph Eichler set an aspirational goal for Manitoba’s place in the cattle industry.

It was his intention to see as many cows on the landscape as there were before BSE devastated the market 15 years before.

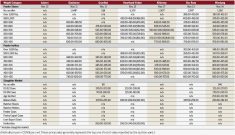

The day he uttered that objective, to a crowded auditorium at Ag Days in Brandon, the province was home to 387,200 beef cows, about half the number in the early 2000s.

Read Also

Farmer mental health support extended in Manitoba

The Manitoba Farmer Wellness Program is slated for $300,000 over the next two years for its farm mental health services

No one knew that Manitoba was on the edge of a years-long dry spell that would see two critically short feed years, spark widespread calls for aid and start an exodus of both livestock and producers from the heart of cattle country.

Rather than celebrating the rebound Eichler hoped for, the industry is now watching the sector wither.

Why it matters: It’s been year after year of hard knocks for the cattle sector and, despite efforts to maintain numbers, Manitoba’s herd size continues to slip and producers continue to tap out.

The dreaded “D” word was already being bandied about by mid-2017. In 2018, summer heat and no rain kept feed supplies tight for patches of the province. In 2019, things were dire enough that municipalities in the northwest and Interlake declared disaster. Producers pushed for government aid and feed shortages prompted the province to put forage insurance under the microscope.

Two years later, in 2021, and with little reprieve between, Manitoba was gripped by the worst drought since the 1980s. Again, the Interlake bore the brunt. Hay prices skyrocketed. Producers winnowed their herds, sometimes sending valued genetics to the sales ring. Fears rose about the number of producers possibly leaving the industry.

Then came spring 2022. Snowstorms and flooding plagued the calving season. Stock losses mounted.

Kirk Kiesman, manager of the Ashern Auction Mart, has a front row seat to the fallout. He estimated that the average producer in his region lost 15 to 20 per cent of the calf crop, three to four times the norm, to say nothing of lingering drought-related difficulties.

There is little doubt in Kiesman’s mind that the region will end the year with fewer cattle and fewer cattle producers.

“Just that high death loss after the drought, it sucked the wind out of a pile of the farmers,” he said.

On-the-ground industry members like Kiesman and organizations like the Manitoba Beef Producers have all reported a slow bleed of farmers giving up on the industry, despite programs meant to encourage them to rebuild.

Bred cattle sales are filling up at the Ashern Auction Mart this fall, Kiesman said. Already, every Saturday in December is booked, as is half of November.

“We’re looking at liquidations,” he said. “Guys don’t have to. The calf prices this fall are looking very strong on the yearlings and the calves, so this is not an ‘I have to sell.’ This is, ‘I’m done with cow-calf’.”

Those who are sticking with the industry are running fewer cattle, he added.

Rather than growing the herd to pre-BSE numbers, cattle in Manitoba have continued to slide. In July 2017, when the province pitched a resurgence, Manitoba boasted 1.14 million cattle, almost 1.1 million of which were on beef farms. By the same time in 2022, those numbers had dropped to 1.01 million, with the beef herd dropping to 928,500.

In the last three years alone, Manitoba had lost more than nine per cent of its beef cows, not counting replacement heifers.

Searching for a tourniquet

Manitoba Beef Producers president Tyler Fulton said it comes down to profitability.

“Let’s be honest, the last couple of years, the expense side of the ledger has had a whole bunch of new line items that we hadn’t really seen before, with all of the extra feed that was purchased or all of the precautions or actions that were taken to address the spring storm,” he said.

Beef producers are getting on in age, he admitted. The average age of Canadian farmers in general is 58, according to the 2021 census. That puts retirement on the table for those who have reached their last straw.

The demographics have certainly hindered industry growth, Fulton said, and with current feeder prices, producers who were considering retirement might think it’s time to bow out.

Still, he said, “if we get a scenario where market prices are consistently 20, 30 per cent above the previously five-year average, then I think we could see a sway back into building cattle numbers over the long run.”

Mapping the route to profitability is the crucial task in question.

Cattle are in tough competition with the grain industry, Fulton said in a September conversation with the . Even with local calf prices netting 30 to 50 cents per pound more than last year, cattle are a hard sell compared to potential income from using that same land for grain.

Fulton said it also comes back to the industry’s long-standing push for better business risk management. The current suite of tools is a poor fit for the livestock sector, both Fulton and Keystone Agricultural Producers president Bill Campbell said in a June article by the Co-operator.

When it comes to AgriStability, the beef sector’s slim margins make it hard to bank profitability year to year, Campbell noted at the time. AgriInvest, which Campbell singled out for its flexibility, has roused federal criticism for the amount of unused money sitting in those accounts.

Fulton has pointed to the disparity in business risk management options between livestock and grain operations. In particular, programs like livestock price insurance could smooth out market risk for producers, but unlike crop insurance, premiums are not cost-shared with government.

That has been a long-time sticking point for the cattle industry.

“We need to level the playing field with respect to business risk management products that can address the biggest risks that we, as farmers, incur. And for us in the beef sector, that’s largely a market price related factor,” Fulton said.

“For crop producers, it’s probably largely production risk. That is addressed by crop insurance. We don’t have something that addresses our largest risk that we’re exposed to.”

Program menu

Most of agro-Manitoba, except for the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border area and the eastern-most municipalities, will be eligible again this year for the federal livestock tax deferral, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada announced in late August.

That marks the fourth time in the last five years that Manitoba farmers have been widely eligible for the provision. It allows farmers to delay paying taxes on animals sold during a year when their region was hit by flood or drought.

The program is meant to lower the tax burden in tough years, with the idea that they will recover herd numbers once things improve.

In Manitoba, the third and final program to come out of AgriRecovery is aimed at herd recovery. The Herd Management Drought Assistance program promised $250 per head for breeding cows culled during the drought and later replaced from auctions or from the producer’s own replacement heifers.

It’s not yet clear how many producers will use the program, although Fulton said he’s heard of little uptake.

A spokesperson from the province said each applicant must be contacted before their participation is confirmed, so numbers are not yet unknown.

Kiesman suggested producers who want to recover their cattle numbers may find the program helpful.

“I think that’s going to be a tool and I think they’ll get some good cows because of it,” he said.

The federal and provincial governments promised $155 million in ad hoc AgriRecovery aid last year.

Crown land

Issues around Crown lands have done little to keep producers in the sector, industry says.

In 2019, the province unveiled new regulations for its modernized Crown lands system. The changes, which included a new market-based rental formula, auction system for allocating leases, shorter 15-year term length and the removal of unit transfers, enraged standing leaseholders.

The province said the new formula was necessary after years of frozen rates that were among the lowest in Western Canada. It was expected to raise rents by 350 per cent over two years, raising major complaints among producers.

They argue that the rent has directly fed into the number of farmers leaving the industry, as well as lack of reinvestment by those who intend to stay.

The Interlake and the Parkland had the most drought-ridden regions of the last three years and some of the most Crown land-reliant ranches in the province.

Dale Myhre, who farms near Crane River, is among producers who feel that double hit. He sees the trickle of producers leaving the sector, many of them young.

His land base is about 25 per cent smaller than it was two years ago, he said, because his farm was forced to give up some Crown land leases last year.

“We couldn’t afford to keep it,” he said.

There has been no investment on the Myhre ranch — no land improvements and no cattle bought — for the last several years.

“The government did give pretty good assistance, so that wasn’t the deciding factor for the people with a lot of Crown land,” Myhre said. “It’s the Crown land issue with the government. They’ve forced all these young people off.

“The old people had to stay on as long as they could. Some of them had to quit because of their age and health but (others) are hanging on because they’ve got 40 years of investment in it and they’re hoping that they don’t have to just give it all away.

“But the young people could leave, because they could go find jobs and they could have a future somewhere else and they don’t have as much of an investment.”

Rent increases tipped leased land (much of which is marshy, bushy, comes with predator problems or has little outside access) past what it could productively offer, Myhre said.

When rents were low, producers could justify the cost of running cattle on those parcels.

Rental costs aren’t the full story, he added. When it comes to long-term viability of the cattle sector in his region, where some farms owe most of their land base to Crown land leases, the lack of unit transfer is a serious problem.

Unit transfer, which allowed producers to transfer lease rights to a new owner if they sold their deeded land, was critical to the value of heavily Crown-land reliant ranches, says the Manitoba Crown Land Leaseholders Association. Without it, the cattle sector has little attraction for newcomers to the industry. Retirement plans for long-standing farmers, which relied on the value brought through unit transfer, have been upended.

The province has argued that unit transfers artificially inflated the value of ranches. However, it has offered rent relief over the next three years, a move it says is directly related to the financial issues brought by drought. Producers will have to pay half their current rental rates next year, followed by a 33 per cent drop from current levels in 2024 and a 15 per cent drop the following year.

The province has also reopened discussion around the Crown lands system that comprises publicly available consultation through EngageMB. In another earlier announcement, it promised help for projects that would increase productivity on leased land.

“The Agricultural Crown Lands program supports a vibrant and sustainable agricultural sector, and our government is committed to ensuring it continues to meet the needs of Manitoba’s livestock industry,” Johnson said in a Sept. 28 statement.

For producers like Myhre, however, the rent reduction gesture is appreciated but provides only a short-term reprieve.

“It’ll get us through next year. It’ll get us through to the next election,” he said.

“We’ve been so let down by the province that to think, ‘oh, they’re going to do something meaningful in the long term.’ No. It’s hard to take them at their word.”

The future

The future of the cattle sector in five years’ time will depend on unknowns, namely the weather and market prices, Fulton said.

“Really, what we’ve been working on is setting it up so that, if these other factors come into play, then there would be motivation to grow the herd, because the profit incentives would be there. At the end of the day, it’s only a sustainable industry if we have some profitability.”

For Crown land leaseholders, the future will depend on provincial government actions.

Myhre said there is a future for the sector in his area if rents are permanently rolled back and unit transfers are reinstated. Under the current scenario, things look bleak.

“If we knew today that that was going to happen, then even though I’m 67, I’d be better to just walk away, because for sure we’ll just get less and less viable,” he said.

Kiesman suggests that smaller, more efficient herds will become the norm, while more land will likely be used for annual crops, even though it is less suitable for grain production than livestock.

Producers approaching retirement have little incentive to keep running large herds, said Kiesman, and cow-calf production is a hard sell for the younger generation.

“I don’t know how many parents are encouraging their kids to take over the cow-calf. I mean, I’d love to see more young people in the cow-calf sector, but after five to seven years of losses, it’s hard to encourage your children to do something that’s losing money.”