Reynald Gauthier isn’t Western Canada’s average millet grower. The mouths he’s feeding are human.

Gauthier, founder of Millet King Foods, has been a champion for the ancient grain, as well as a major seed provider, since the early 2000s. Just over 600 acres of Proso red millet are seeded on his farm near St. Claude every year.

His work to develop millet-based foods spans more than a decade, has cost tens of thousands of dollars, and has included partnerships with the Food Development Centre in Portage la Prairie.

Read Also

Students push for Manitoba road upgrades

Manitoba’s lack of higher-rated RTAC roads creates irritating highway detours and weight restrictions for farmers, University of Manitoba students told KAP.

Why it matters: Although a staple in parts of the world, farmers in Western Canada aren’t lining up to grow millet as a commercial grain.

In the last 15 years, Gauthier appeared several times in the winner’s circle of the Great Manitoba Food Fight. In 2010, he was awarded $10,000 and second place for his Good Old Fashioned Millet Beer, which he hopes will eventually be the cornerstone of a craft brewery. A year later, he returned with Millet King Crunchies, a cereal that netted him the $5,000 third-place prize.

He has developed a waffle and pancake mix and mills some of his millet into flour, which he sells direct to consumers, along with seeds for human consumption.

But while Gauthier sees boundless potential in the food market, most of his seed customers still grow millet to feed cattle.

“Ninety-nine per cent of my farmers, it’s for swath grazing,” he said. “I’ve got a few that chop it for the [silage] pit and a few that wrap the bales and a few that bale it dry and we’ve got a few guys that put it in a silo, because we feed it to the dairy cows.”

This year was designated as the International Year of Millets by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. The family of grains is more friendly to arid climates with fewer inputs than other crops, the FAO says, and could be key in lowering reliance on imported food in vulnerable regions.

The FAO has tagged millets as a cost-effective source of iron, anti-oxidants, protein, fibre and other minerals, as well as a low-cost solution for those who suffer from celiac disease or diabetes, as the grains are gluten free.

There is also the matter of history. The crop has been “overshadowed by other grains over the last decades,” according to the FAO website, but was one of the first domesticated crops and is culturally significant in many regions of the world.

Little local use

The theme is not exactly geared to North America, where millet makes up a fraction of cereal production.

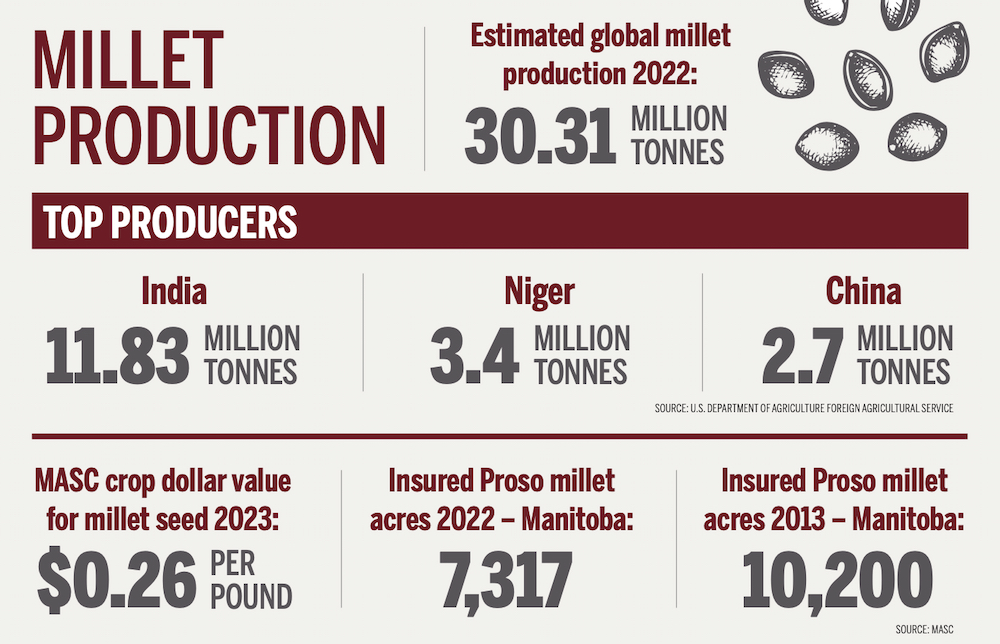

In 2022, the Manitoba Agricultural Services Corporation insured just over 7,300 acres of grain or seed millet, down from just over 11,000 acres the year before.

“It’s such a funny crop because it’s so important for people throughout the world. Except in Canada, you don’t hear about people eating it very often,” said Manitoba Agriculture cereal specialist Anne Kirk. “In Manitoba, we do typically hear about millet as a forage crop, typically a later season crop.”

Proso millet acres range from 3,000 to 5,000 acres annually, Kirk noted.

While millet is hardly an economic driver in Canadian agriculture, international attention has led Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada to highlight its work with the crop.

AAFC has described the lesser known cereal as “a nutritionist’s dream: rich with fibre, protein, antioxidants and minerals like zinc and iron,” while also pointing to its 80-day life cycle and general resilience.

“This nutritional powerhouse can be successfully grown in many areas of the world, including Canada. Unfortunately, despite the crop’s potential, little millet is among the least studied crops,” an early 2023 publication read.

A joint project between AAFC scientists in Saskatoon and researchers in India has yielded a genetic atlas to help fill that gap. It documents millet’s desirable food traits across its life cycle, with the hope that those traits could be enhanced as new varieties are developed.

Elsewhere, projects through Living Labs, a federal program that tests novel crop management, have tagged millet for use as a cover crop in Maritime potato production. Another project hopes to gauge the combination of pearl millet and sweet sorghum as a dual-use crop for biofuel and silage.

Uphill battle

Millet’s status as a warm season crop is a major reason it has more traction as a forage, Kirk noted. It thrives in hot, dry conditions that might hinder other feed options in a drought year.

As a grain crop, “it can do quite well in Manitoba, depending on the environmental conditions,” said Kirk, and has a planting and harvest window similar to corn.

It is often the last crop the farmer will plant, according to Gauthier.

“Millet doesn’t like to go in the cold ground. It needs to be room temperature before you can seed it or hotter, and then it comes up right away.”

As far as Gauthier is concerned, the late seeding date is both the crop’s nemesis and a chance to dig itself a niche in the grain sector. It could be a viable option in wet years, for example, when yield curves for more popular crops are already dipping by the time farmers get on the field.

Millet King’s seed business had a great season in early 2022 for that very reason.

“Last year we were busy,” Gauthier said. “I was in the hospital last July for a week and I was selling seed while I was in hospital.”

He estimates that he sold about 3,500 pounds of seed in that week alone, largely for forage production. Spring conditions also led to a surge of millet acres around his home region of St. Claude. Gauthier estimated that about 1,500 acres of millet were grown in the area.

The back end of the season presents another challenge.

Kirk noted that, given Manitoba’s temperamental autumn weather, a producer might plan to harvest in September but end up slogging through the field in November. That would lead to significant drying costs.

And millet is a bit fussy when it comes to drying, Gauthier said. Put the dryer on high and it will cook the grain.

He typically harvests his crop in late September or the first days of October.

Where’s the market?

Manitoba’s growth in corn and soybean acres proves that longer-season crops can gain a foothold in the province.

Part of millet’s problem can be traced to lack of markets. More millet is sold for birdseed than for human consumption.

Dan DeRuyck, whose Top of the Hill Farm near Treherne provides organic grain cleaning and milling, does a limited business in millet and his farm no longer grows it. DeRuyck said he might process around 12,000 pounds a year. The cleaned and de-hulled cereal from their operation is sold mostly to bakeries for use in multi-grain baking.

“It’s not one of our biggest sellers,” he said. “It was just something that we started pre-COVID, so we were still working on markets at that point.”

Those efforts hit another roadblock with inflation, he noted. Customers were less likely to reach for specialty ingredients with food inflation hitting double digits. Millet sales are below expectations as a result, he said, although trade has started to pick up.

Weather and weeds

Inconsistent yields may be another factor in the crop’s lack of popularity. MASC data shows average yields between 1,800 and 3,500 pounds per acre, lower than other warm season crops, according to Kirk.

In a good year, Gauthier expects to reap one million pounds but hasn’t met that bar in the last two seasons. He estimated that he took about half a crop in 2022, after flooding forced him to seed about 45 days late, even by millet standards. The crop froze before harvest.

The year before, drought also led to a 50 per cent crop.

Millet has a problem common to many niche crops: lack of production knowledge under Manitoba conditions. There may also be bias against a crop that producers still consider to be a weed. Its family includes foxtail millet, and Kirk noted volunteer millet could become a weed in future warm season crops.

However, DeRuyck said that in his experience, there are few weed issues within the millet itself.

That’s one reason Gauthier bumps his seeding rates to 50 pounds an acre.

“Nothing can grow between that. You’ve got very, very thick stubble,” he said. “Now I’m at the point where I’m seeding direct.”

Potential

If producers want to pick a year to grow millet, Gauthier suggested this year might be favourable, since prices for the birdseed market are 28 to 30 cents a pound.

“Usually it’s not that high. Usually it’s anywhere between 12 and 16.”

He also expects demand at Canadian dinner tables to expand in the next few years, creating stronger markets.

DeRuyck also believes there is room to grow. Millets may be a staple in other parts of the world, he noted, but it is still a novel food in Canada. The average consumer may not see it as an option or feel confident in using it.

Gauthier pointed to immigration from areas where millet is the norm, such as southeast Asia or Africa. That has created a potential customer base.

His own entrepreneurial endeavors may also play into market development, he said.

The same cereal that won accolades in the Great Manitoba Food Fight is in the final stages of commercialization, and he averages two sales of flour or food-use seed a week.

“It’s like anything else. When you drive your car on the highway, you go slow and you accelerate,” he said.