Those suing the province in a class-action lawsuit driven by 2011 flooding around Lake Manitoba have got a possible dollar amount for their settlement — pending approval by the courts.

Why it matters: The 2011 flood may have been a decade ago, but a legal question around Lake Manitoba flooding that year is just now approaching the finish line.

On Nov. 18, Justice Joan McKelvey gave the nod to a pre-approval order for the 2011 Lake Manitoba Flood Class Action Settlement Agreement, in which the Government of Manitoba agreed to pay out $85.5 million, without any admission of wrongdoing.

Read Also

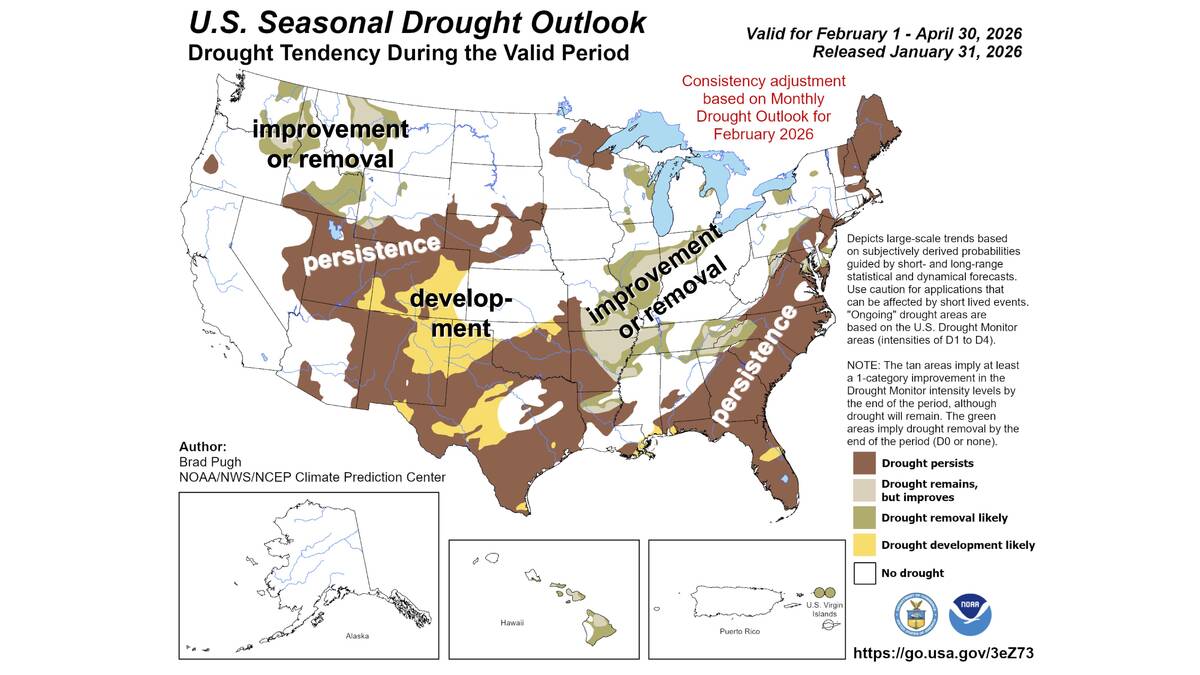

Neutral conditions drive 2026 weather as La Niña subsides

U.S. government meteorologist expects there will be neutral ENSO conditions for the 2026 farm growing season.

Claimants must now wait for final court approval of the settlement early next year. An approval hearing has been set for the morning of Jan. 13, 2022, to be held over video link.

The class-action suit covers anyone who had property within 30 kilometres of Lake Manitoba that was damaged due to the 2011 flood, with the exception of First Nation reserve land.

According to a notice put out by the province, damage or loss to any primary or secondary residence, business or farm (including equipment or vehicles, herd loss or crop production loss either in 2011 or since) is eligible under the settlement. That list also extends to the costs of repairing or mitigating the flood’s impact, loss of business, or costs of moving, storage or accommodation during the flood.

Background

The issue has been in the court system since March of 2013, when plaintiffs filed a suit claiming that the Government of Manitoba’s use of water control infrastructure during the 2011 flood directly caused the flooding in some areas around Lake Manitoba.

This year marked the 10-year anniversary of a flood that caused billions in damage and led to flood plan overhauls in the wake of the disaster.

Going into spring 2011, the province had already been fighting for months to prepare for a flood.

Water was already high on Lake Manitoba in 2010, thanks to rain. In the north end of the lake, the Fairford River Control Structure had been opened wide until November 2010 (and again in early 2011) in an effort to lower levels and make room for the anticipated spring glut.

Winter weather had also set the stage for deep snowpack, while wet weather the previous year had left little wiggle room for soil water infiltration.

By March 2011, the Shellmouth reservoir had been drawn down to historically low levels, while efforts to bolster the dike along the Assiniboine River near Portage la Prairie were undertaken that February.

Then came the snowmelt. Despite preparations, spring run-off overran the spillway at the Shellmouth dam. Exacerbating the problem, yet more water came in the form of significant rainfall through the spring and summer, eventually sparking concern that water would breach the dike along the Assiniboine River.

In response, the province turned to the Portage Diversion — and at one point, a controlled breach of the Hoop and Holler Bend that led to overland flooding in the surrounding area. Between April 1 and Aug. 5, 2011, the diversion drained over 4.7 million acre-feet of water into Lake Manitoba, according to background provided in the June 11 decision from McKelvey.

The 2011 flood eventually saw severe flooding around Lake Manitoba through most of the summer that year.

Taken to court

The lawsuit kicked off legal proceedings that have now stretched over 7-1/2 years.

A statement of claim, dated Aug. 7, 2014, plaintiffs Fred Pisclevish, John Howden, Stephen Moran, Shaun Moran, Alex McDermid, Keith McDermind, Sunshine Resort Ltd. and a numbered company 5904511 Manitoba Ltd., initially asked for $250 million as well as $10 million in aggravated damages.

On April 18, 2018, courts certified the lawsuit as a class action.

This year, the suit went to trial, presided over by McKelvey. The three-week trial spread from late February to early March 2021.

The decision from the bench, published June 11, ruled that the province’s actions did, in fact, cause flooding that “substantially interfered with the use and enjoyment of the real property interests of the class.”

“In all the circumstances, and particularly with a careful consideration of the evidence of the lay witnesses as to the devastation occasioned with each of their properties, I am satisfied that substantial interference has transpired,” McKelvey said, in part.

Settlement negotiations kicked off following that judgment, but “prior to any appeal,” according to a spokesperson from the province.

“The 2011 flood has cost Manitobans over $2 billion,” they added, also linking the issue to the Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin Channel project.

“This project is the final step in Manitoba’s long-term climate resiliency and flood mitigation plan and is essential to protecting all Manitobans,” the provincial spokesperson said.

That project would increase flow capacity between Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg through two new flood channels. Proponents argue that those structures would help speed the flow of excess water out of Lake Manitoba in the case of another flood like 2011. The project has also seen several regulatory delays, including issues with environmental approval, and some local push-back since being proposed.

Next steps

Anyone eligible under the class-action lawsuit has until the end of the year to submit any comments (including legal fee amounts) they would like considered at the Jan. 13 hearing. Comments must be submitted in writing to the law firm, DD West LLP.

The court must approve the settlement before any payments are made.