On a scale of one to 10, how floppy are these wheat plants?

That’s not exactly how researchers define the canopy architecture of wheat, but “eyeballing it” has been a key part of the process. With better imaging technology though, the hope is those assessments can reduce much of that subjectivity.

TerraByte Labs at the University of Winnipeg is refining a tool that can create 3D renderings of wheat plants and give precise measurements of their structure, detecting characteristics much earlier.

Read Also

Dry bean breeding has paid off for farmers

Experts say they’ve seen the payoff in yield and farmer profit as better dry bean varieties have hit the scene in Manitoba and surrounding regions.

WHY IT MATTERS: The ability to create 3D scans of plants could speed up crop breeding through precise measurements and detection of minute differences in plant genotypes, potentially putting new, useful varieties in the hands of farmers faster.

That kind of plant architecture is one of the many genetic traits that crop breeders might select for when chasing a particular outcome. The angle at which wheat leaves grow is a good predictor of canopy structure — how floppy or erect the plants are — notes doctoral student Kalhari Manawasinghe. That in turn affects plant resilience to heat stress. More floppy plants equal less ability to shed heat and less airflow within the stand of wheat.

The imaging setup inside TerraByte Labs can precisely measure that leaf angle.

“You can imagine that breeders only need to grow their seedlings for one week, and then can predict what type of canopy architecture those plants will be,” said University of Saskatchewan plant science professor Karen Tanino. “That’s a big advantage.”

The making of an image

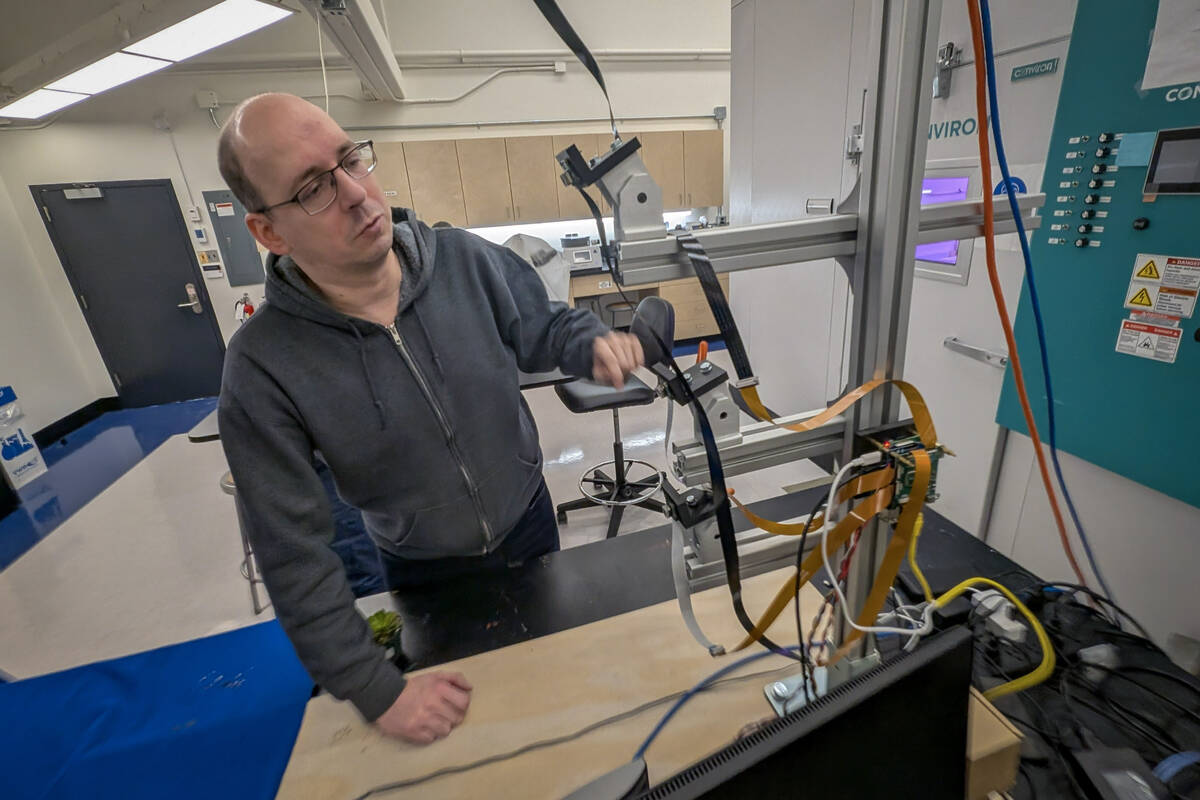

The setup is composed of a checkerboard-patterned turntable on a blue fabric backdrop. Four small cameras face the turntable at different angles.

Once fired up, a computer controls the turntable to spin a given plant, stop it at precise intervals, and take its picture. These photos become the basis of the plant’s 3D rendering, featuring precise metrics — like the height and radius of the plant, or the angle of the leaves.

“You take out that human bias out of these measurements,” said Michael Beck, assistant professor of applied computer science at the University of Winnipeg.

The process is called photogrammetry. It’s often used to create 2D or 3D models of buildings or bridges. Beck and his colleague, department of physics professor Chris Bidinosti, were inspired by museums that use photogrammetry to scan artifacts, a University of Winnipeg article says.

The turntable setup isn’t the only photography rig in the lab, but it’s the cheapest by an order of magnitude. It was built with relatively low-cost cameras and runs off an inexpensive Raspberry Pi single-board computer.

The whole setup cost about $2,000 — though Beck said they could do it cheaper. By comparison, the other rigs in the lab cost $70,000 and $20,000.

Wheat in 3D

It takes maybe 15 minutes to for the photogrammetry setup to take pictures of each plant. Rendering the 3D image takes a lot longer — though this can be done automatically by a computer overnight, said Beck.

Students are researching how to shorten the process. Even as it is though, the it could save plant breeders a lot of time.

Breeders may deal with hundreds of thousands of seedlings, Tanino said. There’s only so many people they can hire to help evaluate the structure of the plants. “Breeders are always looking for high throughput,” she noted.

Bits and (flea beetle) bites

At present, Manawasinghe sends seeds to Winnipeg to be grown and the plants photographed there, then compares results in the lab to plants she grows under high tunnels at the University of Saskatchewan.

The folks at TerraByte Labs are the experts in data extraction, Tanino said, so they leave that aspect of the research to the computer scientists.

Down the road, it may be feasible for the University of Saskatchewan to have its own photogrammetry setup. Bidinosti and Beck plan to develop more user-friendly software and to get the price of the rig down to around $1,000, the University of Winnipeg article says.

The setup can also be modified for other projects. One University of Manitoba student is working on a project that would scan wheat heads and detect each individual kernel. A similar system at the University of Manitoba is also being used to assess flea beetle damage.