Farmers aren’t the only ones dealing with risk management dilemmas these days. Insurance costs are rising rapidly across the board.

One industry website recently suggested that car insurance rates in Ontario could climb by as much as 25 per cent, or about $600 per vehicle.

One reason is the inflated cost of cars, which obviously increases the size of the payout. But the single largest reason is auto thefts, which have reached epidemic proportions in parts of the country.

Read Also

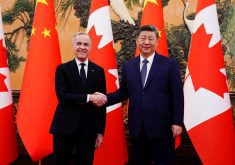

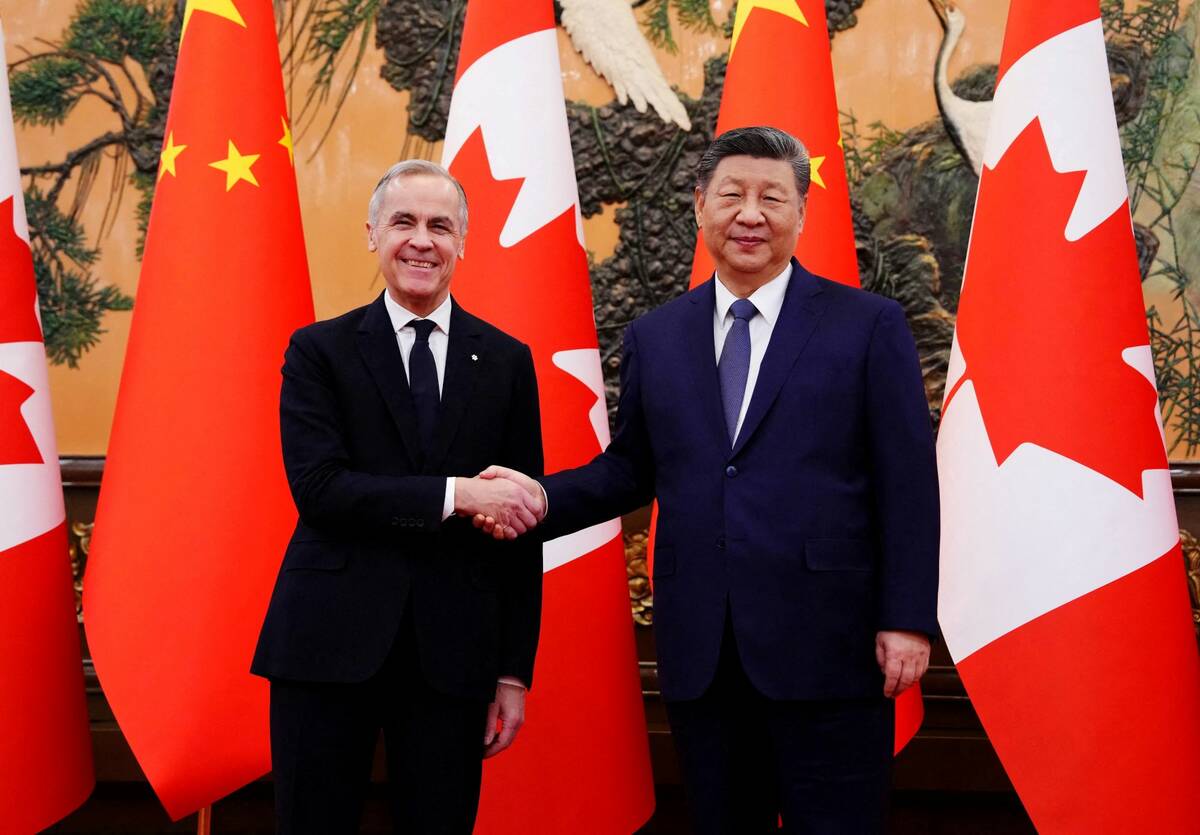

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China is a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

Some firms are adding a $500 surcharge to policies for vehicles that are commonly stolen. Eventually that could lead to cars that are uninsurable at any cost. It’s not like there isn’t historical precedent. I’m familiar with one from the U.K.

In the mid-1980s, Ford introduced the Ford Sierra RS Cosworth. It was a skunkworks design based on a boxy economy car. In conjunction with high-performance engine designer Cosworth, Ford jammed in a turbocharged, intercooled engine that gave it a top speed of nearly 160 miles an hour.

Unfortunately, the makers failed to realize it would be an attractive target for auto thieves and failed to upgrade the car’s security. Automotive journalist Richard Hammond summed it up as “a car with the performance of a supercar, and the locks of a shed.”

It was also faster than anything the U.K. police had on the road at the time, leading to numerous high-speed pursuits. Car thieves would reportedly see the Sierra RS on the street, follow it home and steal it later. It was especially prized by armed robbers looking for a quick getaway car.

In the end, a car that cost £7,000 to drive off the showroom floor cost twice as much to insure annually — if the buyer could even find coverage.

Real estate insurance costs are also rising. One survey suggests Canadians will, on average, see a 7.6 per cent increase in premiums in 2024. Several factors are weighing in — high claim costs and more expensive repairs and replacements, for example.

But the biggest single issue, according to surveyed insurers, is increased disaster claims that many link to climate change.

Some insurance firms are even exiting the highest-risk markets, and not just in far-flung parts of the globe. It’s happening here in Canada, albeit at a micro level. In the U.S., several insurance firms have pulled out of entire states, like low-lying hurricane-battered Louisiana. Here, it’s linked to more localized risks.

The Insurance Bureau of Canada in 2021 told CBC’s Marketplace that as many as 10 per cent of Canada’s homes were “uninsurable due to flooding.” An executive with the group noted that as risks from climate change increase, more Canadians could find themselves uninsurable.

Increased premiums are one thing but not being able to insure a home essentially means the owner can’t borrow against it either. The point is that the insurance business clearly has a threshold at which it is more than willing to walk away.

Which brings us to agriculture, quite probably the most weather-exposed industry in the world. The trend is clear. Crop insurance and disaster recovery payments are both rising.

In 2021, for example, more than $650 million in crop insurance payments were made in Manitoba, more than double the previous record. That same year, Alberta broke $1 billion in crop insurance payments.

Were crop insurance a product of the free market, rather than a cost-shared arrangement between the federal and provincial governments and farmers, I have no doubt premiums would be increasing rapidly.

In Manitoba, on most crops farmers cover 40 per cent of insurance premiums while the federal and provincial governments account for 36 and 24 per cent, respectively. Similar formulas are in play in other provinces.

That means keeping crop insurance on the “actuarily sound” footing under which it’s designed to function requires a lot of public dollars.

Most Canadians recognize farming is risky business, and weather risk is the one of the biggest issues the sector faces.

But if payouts continue to rise, there may come a time when programs like these become too expensive to be sustainable in their present form. Farmers and governments could be confronted with demands to reduce the public’s exposure to the production risks farmers face.

This is why the sector should embrace climate change adaptation where possible and fund research to enable it. Reducing the risk of losses is better than insurance after the fact.