As we near the mid-point of summer, and even though it hasn’t felt like it lately, we are heading into peak thunderstorm season.

Over the last month or so, I have discussed atmospheric stability and instability and how this can lead to the development of thunderstorms. We investigated what it takes for a regular thunderstorm to become severe and delved into the mechanisms behind different types of severe weather associated with thunderstorms, such as hail and high winds.

Then we looked at the most destructive yet awesome weather event associated with thunderstorms — tornadoes.

Read Also

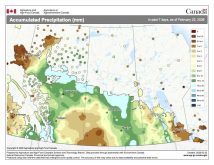

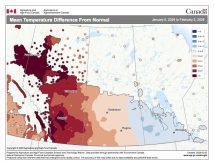

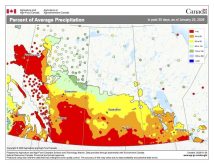

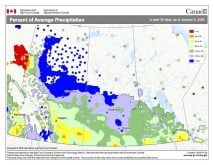

VIDEO: What climate change data gets wrong about the Prairies

Precipitation, not temperature, may be a better gauge of climate change impact on the Prairies, says director of the Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative.

As good as our technology is, we are still not 100 per cent sure how tornadoes come to be, so let’s look at:

- Supercell theory;

- Rear-flank downdraft theory;

- Tornado vortex theory; and

- Multiple vortex theory.

The birth of a tornado

The first two theories listed are kind of tied together, as they both involve supercell thunderstorms. To understand these two theories, we need to understand what a supercell thunderstorm is.

Thunderstorms are fueled by the presence of warm, moist air near the surface and colder air aloft. What makes a supercell thunderstorm different from a regular thunderstorm is the ability to sustain a rotating updraft. These storms can rotate due to wind shear, or the change in wind speed and direction with height.

As a supercell thunderstorm evolves and the updraft intensifies, it draws warm, moist air into the storm, which helps drive further development. With the right type of wind shear, the updraft becomes tilted, which does two things: It helps keep the updraft separate from the downdraft, allowing the storm to continue growing, and it starts to stretch and squeeze the rotating column of air vertically, making it spin faster.

This stretching and squeezing of the rising, rotating column of air is what scientists believe leads to development of tornadoes, but the exact mechanism is not fully understood.

This leads to the second theory of tornado formation: rear-flank downdraft.

As the supercell thunderstorm evolves, a region of cool, descending air develops on the back side of the storm. This is the downdraft that all storms have, but due to the wind shear tilting the storm, this downdraft does not come crashing down.

Instead, it can interact with the updraft by enhancing the low-level inflow and rotation, which in turn can be pulled into the updraft of the supercell, leading to increased likelihood of a tornado.

Tornado vortex theory

The tornado vortex theory is similar to the supercell theory. It simply builds (or rather, almost simplifies) that theory. It states that tornadoes form when horizontal spinning air in the storm updraft is tilted vertically by a strong updraft.

These updrafts can be moving very fast and, as the air rises, it stretches and tightens or contracts the rotating column of air, much like a figure skater pulling in their arms when spinning.

This causes an increase in spin rate due to conservation of angular momentum. This process is known as vortex stretching and the intensified spinning motion within the storm may lead to formation of a tornado.

Multiple vortex theory

As the name suggests, the main vortex within a thunderstorm contains multiple smaller vortices rotating within the main circulation. These can appear as satellite tornadoes or as sub-vortices within the primary tornado.

This phenomenon results in a tornado with a more intricate appearance, often displaying a spiral pattern of swirling winds within the main funnel.

According to the multiple vortex theory, the main column of rising, rotating air serves as the parent vortex and provides the circulation or rotation necessary for the formation of the tornado.

As the parent vortex intensifies, it can spawn smaller satellite vortices. These are typically found rotating around the main funnel cloud.

The interactions between these satellite vortices can create a complex pattern as the individual vortices merge, split and interact with each other. This can result in a rapid change in shape, size and intensity of the tornado. The chaotic behavior can help explain the erratic movement and characteristics we sometimes see in tornadoes.

How these satellite vortices are formed is still not known. If you remember the discussion on formation of low-pressure areas and how they can randomly spin up along a boundary of opposite moving air, picture the same thing happening on a much smaller scale and a much, much faster speed.

The constantly changing environment within the storm and the landscape over which the storm is travelling can cause these satellite vortices to spin up, grow larger, and then simply die away.

I think all the theories bring something to the table and, as with most complex systems, it is probably a combination that leads to formation of tornadoes. The one thing the theories have in common is the need for a strong, well-established thunderstorm that either has rotation or is in an environment where columns of air can gain rotation.

Hopefully, as technology gets better, research will lead to a definitive answer on the formation of tornadoes, in turn leading to better warnings.

Next on our list of severe summer weather is something that kills more people than any other severe weather event — heatwaves.