The first deer was standing, unconcerned, on the edge of the highway near Holland as I drove past. It was the middle of the day.

Then there were a few more chowing down on the remains of a bale and a veritable conga line of them along the railway near Treherne.

The next day, in a field just below the Manitoba Escarpment, you would have sworn the landowner was farming deer.

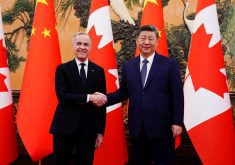

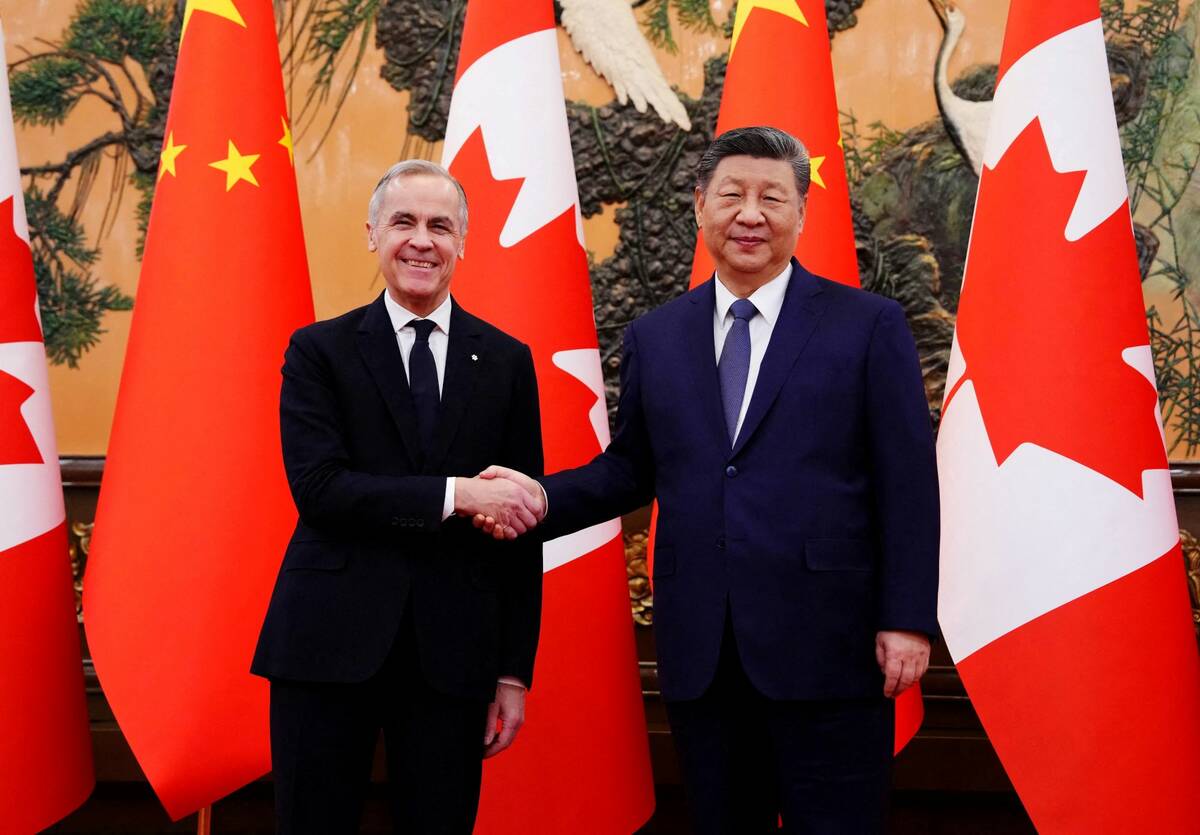

Read Also

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China is a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

It’s no surprise to see deer moving at this time of year but, according to recent media reports, it sure seems like there’s more of them in parts of the Prairies.

One recent article dissected what its sources call an out-of-control deer population in Saskatchewan. Farmers interviewed for the article cite dozens of sightings each night, plus feed losses, damage to yards and trees and an uptick in coyote problems.

They also highlight one of Manitoba’s newest diseases: chronic wasting disease (CWD).

It’s fatal to cervids and is of the same family as BSE, and has unfortunately dug a significant foothold in provinces to our west.

Saskatchewan’s CWD monitoring program, based largely on hunter submissions, found 644 positive cases out of 3,300 samples in the 2021-22 hunting season. Of those, 459 were mule deer, but 167 were white-tails and 16 were elk.

In Alberta in 2022, a similar program had 714 positives out of 4,517 tests, 575 of which were mule deer and 129 of which were white-tails. A handful of moose and elk samples also tested positive.

In terms of direct farm hits, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has found three CWD cases in domestic elk in Saskatchewan or Alberta so far this year. In 2022, six farms fell prey, making it a relatively good year compared to 13 domestic deer or elk herds infected in 2021 and 15 in 2020.

Manitoba does not want to get to that point.

We’re still in the beginning phases of our experience with CWD. The first cases showed up in late 2021.

To the province’s credit, those cases spurred official action. Control zones with more vigorous monitoring were introduced and population control measures were put in place.

Until that point, mule deer were a protected species and could not be hunted. They were on the table when the next time hunting season rolled around. Licence holders can now obtain three mule deer tags a year.

In December 2022, the province also announced a winter hunting season for mule deer in parts of the province. Hunting season 2022 also came with much more attention on Manitoba’s own CWD monitoring program and mandatory submission zones.

Despite all that, the future of CWD management in Manitoba looks like an uphill battle.

The inherent issues with managing disease in wild populations go without saying, particularly with the much higher levels of infection in the province next door.

And while efforts during the last hunting season were designed to detect infections and lay the groundwork for prevention in Manitoba, the number of samples overwhelmed the capacity of accredited labs to process them, according to the province’s CWD test result portal. The website warns tag-holders to expect delays of 16 to 20 weeks.

What does that mean for future years of CWD management?

Compared to Alberta or Saskatchewan, Manitoba’s numbers are still small, although the province saw its first cases in white-tailed deer this year. Those two cases, reported in early March, were found hundreds of kilometres apart, with one in the northwest near Roblin and the other in the southwest in the RM of Grassland.

Only 20 cases were found between late 2021 and the start of March this year.

But the overwhelmed labs this winter suggest another look at testing program logistics might be an order, especially if hunter submissions start to climb.

Manitoba’s elk industry has its own roles to set itself up for success. There has not been a CWD case in farmed animals in Manitoba, and the industry wants to keep it that way.

The Manitoba Elk Growers Association urges its members to sign on with the CFIA’s voluntary CWD Herd Certification Program, which includes a regimen of testing, record keeping and biosecurity.

The association has said certification is important for opening markets, but after changes in 2018, it’s also the only way for a producer to get any support from the CFIA, beyond disease traceability, should CWD be found on their farm. That includes orders to destroy animals or compensation for loss.

It may not be possible to close the lid on CWD, but if Manitoba waits until it has a big problem, that problem is here to stay.