The degree of devastation across Canada in 2023 was difficult to comprehend.

It was not a pretty picture, given countless scenes of charred landscapes, scorched shells of former homes, and debris piles as evidence of powerful tempests, dried out riverbeds, and fields underwater as far as you could see.

Beautiful sunrises and sunsets belied the hazy yellow-orange sky that you often could smell and taste – not the pristine, fresh air that is so much part of the Canadian environment.

Read Also

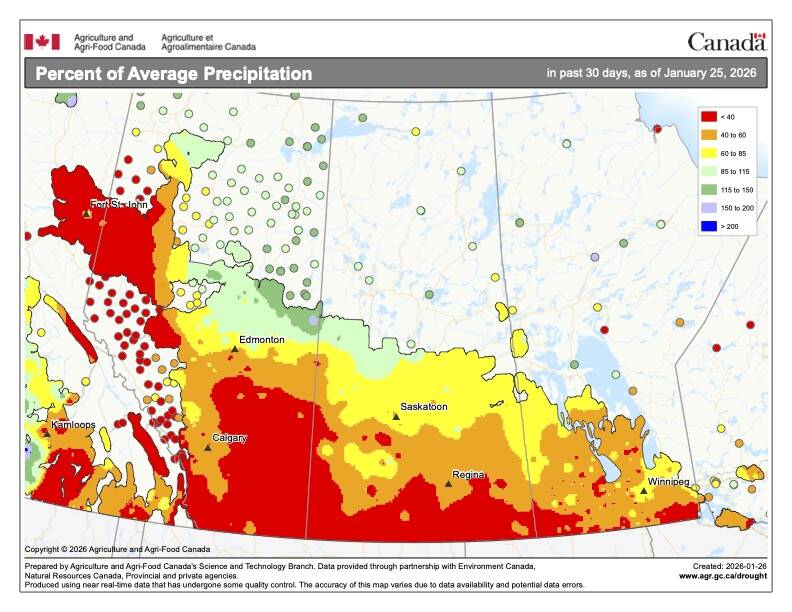

What’s the weather for last half of winter 2025-2026?

A last look at 2025 temperature and precipitation on the Prairies, plus what weather forecasters expect through to spring 2026.

The extremes we saw in 2023 were devastating in many ways, but this is what climate change looks and feels like. We had a preview of what the future could bring if emissions of greenhouse gases are not rapidly curtailed.

As the climate continues to warm, one can expect increasing wildfires, more intense droughts and hurricanes and more intense heat waves.

Not in 28 years of compiling the top annual weather events has there been a more obvious number one story than record wildfires in 2023. In fact, it could have represented four stories in one this year: record area burned, continuation of multi-year drought, torrid heat and foul smoky skies for months on end.

At times, out-of-control fires burned in nearly every province and territory. It was a story that captured international attention for much of the year.

Fighting wildfires across Canada was a national preoccupation over three seasons, not the usual summer-long activity. In the end, 2023 was the worst wildfire year on record – at least twice the previous worst year and seven times the 10-year average of forests consumed by fires. Entire cities and several Indigenous communities were emptied by the threat of wildfires.

Unbelievably, the area burned by wildfires stretched over 18 million hectares. One expert said that more than half the countries in the world could fit their geography into the total area burned this year in Canada.

The Earth’s average temperature this summer was one for the record books. Moreover, 2023 is very likely to be the warmest year in possibly 125,000 years.

For Canada, it was the warmest summer in 76 years, dating back to the start of national record-keeping in 1948. Even more noteworthy, if you include May and September, each province and territory recorded their warmest five months on record, with the exception of Atlantic Canada.

Warm coastal waters resulted in the hottest ever marine heat wave in Canadian waters. Parts of the Prairie provinces went from slush in late April to sweat in early May, practically making spring a no-show. In Eastern Canada, it was the longest “hot season” on record with days above 30 C for the first time in April and October.

In late January and February, a lobe of the polar vortex dipped southward, pushing from the north to west to east. Across the West, temperatures averaged five to 15 degrees colder than normal for some of the lowest temperature departures in a generation.

With biting winds, temperatures felt as low as -59 C with wind chill in northern Québec. Hydro utilities struggled to keep up with power demands, leading to record consumption. Even ski resorts reduced hours of operation because it was just too cold to ski.

It was a year when Western Canada had too little precipitation – unable to get a drop of rain to squelch wildfires or relieve drought, and the East had too much precipitation – just too wet for too long and too often.

Before the Easter weekend, a powerful late-season storm moved into the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence region, bringing widespread freezing rain, ice pellets, hail and heavy rains. Power outages affected over one million customers in Québec and Ontario.

Flooding was another big story this year, including the new age flood of an urban kind in Prairie cities such as Calgary, Edmonton, Regina, Winnipeg, and two- or three-times in Eastern cities like Québec City, Ottawa and Montréal.

Outside of Halifax, six weeks after fast-moving wildfires burned through the western half of the province, the region was hit by torrential downpours resulting in the devastating loss of four people, including two young children. Floods also caused unimaginable damage to personal property and infrastructure.

Initial forecasts predicted a quieter start to the Atlantic hurricane season compared to the past six years but unseasonably warm Atlantic Ocean waters led to another very active tropical storm season.

Canada was touched by the remains of two major hurricanes: Franklin and Lee. Lee was the most powerful hurricane to affect Canada, but it was no Fiona.

On Sept. 16, post-tropical Lee lashed the region with strong winds and heavy rains. Power outages from wind gusts topping 117 km/h in Nova Scotia and around the Bay of Fundy in New Brunswick grew storm surges with a peak wave of 16 metres that destroyed precious beach and park properties along exposed shorelines. In total, the Atlantic basin had 19 named storms, including seven hurricanes, three of them major.

It is challenging to obtain an accurate count of tornadoes, as they are difficult to confirm and may go undetected in rural areas. The estimate in 2023 is around 82 tornadoes in Canada. Of significance, a Canada Day tornado in Alberta ranked EF4 with strongest estimated wind speed of 275 km/h. It was said to be the most powerful Alberta twister since Edmonton’s major tornado in 1987.

Based on preliminary estimates compiled by Catastrophe Indices and Quantification Inc., there were 27 major weather events from December 2022 to November 2023, each with insured cost losses of at least $30 million and with an aggregate loss approaching $3.5 billion.

It will be months before the insurance industry tallies final figures, and it will be only a fraction of the actual cost to properties, businesses and infrastructure, and emotional costs to affected Canadians.