I recently received a simple question and thought I had a quick answer. But once I started to look at it, the answer was more complex than I thought. I went back through the articles I have written over the years and to my surprise, I have never directly discussed this.

The question is: what causes areas of high and low pressure to form?

Before we look at this topic, the global temperature analysis for May has come out and the planet recorded another record warm month. This makes 12 months in a row with record-breaking global temperatures, with 11 of those more than 1.5 C above the preindustrial average temperature.

Read Also

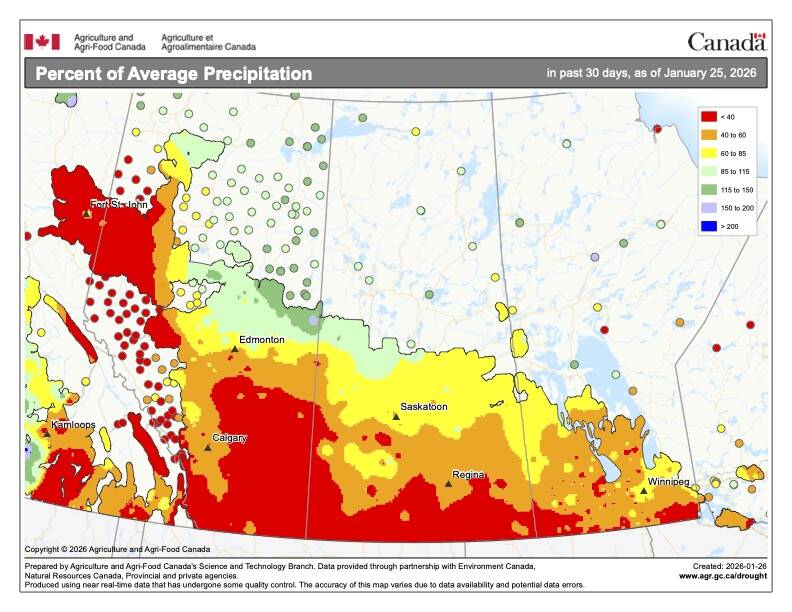

What’s the weather for last half of winter 2025-2026?

A last look at 2025 temperature and precipitation on the Prairies, plus what weather forecasters expect through to spring 2026.

May’s global average temperature was 1.52 C above the preindustrial average (1850-1900) or 0.65 C warmer than the 1991-2020 average. The average global temperature over the last 12 months was 1.65 C above the preindustrial average, or 0.75 C warmer than the 1991-2020 average.

Compared to average, global temperatures have been cooling slightly over the last three months but remain well above record averages. With development of La Nina conditions, global temperatures are expected to continue to cool, but to what extent is uncertain.

Now to our question. Why do we have areas of high and low pressure and what causes them?

First we need to look at the big picture and work our way to more regional reasons. We know that strong sunshine along equatorial regions results in warm air, which wants to rise. When it rises, there is less air pushing down over that region. Since air pressure is basically a measure of the mass of air pushing down over an area, this region has low pressure – at leastlower than the region around it.

This is known as a thermally created area of low pressure. We see the same thing happen at the poles but opposite. The low amount of sunshine results in cold heavy air, which sinks and results in an area of high pressure. This is known as a thermally created high.

If the Earth didn’t rotate, our understanding of high and low pressure and what creates it would end. But as the planet rotates, it creates all sorts of complex interactions.

The rotation of Earth causes winds to be deflected to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. So, on a simplified Earth, the air moving downward in the region of high pressure over the poles would hit the ground and begin to flow toward the equator.

In the Northern Hemisphere, this flow would be deflected to the west, eventually resulting in all the winds blowing from east to west. Conversely, rising air along the equator means that air flows in from the poles to replace it. This air is also deflected to the right in the Northern Hemisphere, creating the easterly trade winds.

If you live in the arctic or the tropics, you would have no problems with this picture, because in these regions the prevailing winds are easterly. In our neck of the woods, we have to scratch our heads, because our winds don’t seem to follow this simple scenario. Our prevailing winds blow from west to east.

Obviously, something more is going on with the atmosphere. Our Earth isn’t a simple place, and this pretty much holds true no matter where you look. The atmosphere is no exception.

Our simple picture of thermally induced low pressure at the equator and high pressure at the poles is augmented by a couple more regions of low and high pressure. These regions are known as dynamically induced areas of high and low pressure.

Dynamic high- and low-pressure regions are created not by intense heating or cooling, but by mechanically forcing air to either rise or sink. The first of these are the subtropical highs, the desert regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

As warm air rises at the equator, it spreads out as it encounters the top of the atmosphere. As it flows northward and southward, it is also pushed downward. This is due to two factors; the air is cooling; and it is converging or bunching up as the large amount of air rising over the equator moves into a smaller and smaller area as it works its way toward the poles.

As this air is pushed downward, it is compressed, heating up the air. Once this air reaches the ground, it spreads out once again. Some turns toward the equator and some heads north toward the poles. It is this northerly flow that gives us our westerly winds.

The second dynamically induced region is an area of low pressure known as the sub polar low. This region of general low pressure is around 60 degrees latitude. Much like the sub-tropical high, this area is formed when the air flowing northward from the sub-tropical high (the westerly winds) bumps up against the southward flowing polar air.

This forces the air upward, which lessens the downward push and creates an area of low pressure.

Things get even more complex when we look at converging and diverging air, and the curvature of air flow and how it can develop areas of high or low pressure. Just remember that high pressure means air moving toward the surface of the earth and low pressure means air is moving away from the surface.