I recently sat down at my computer to see a message from a proudly Canadian crop chem company, announcing its plan to seek an expanded label for a nematicide to cover soybean cyst nematode (SCN) for the 2026 growing season.

That got my attention — because ready or not, SCN has made it to the Prairies. It made its first appearance in Manitoba in 2019 and, as of 2024, was found to be present in soy fields in five municipalitiess (Thompson, Norfolk-Treherne, Rhineland, Emerson-Franklin and Montcalm).

The pest has already become a significant problem for soy growers in the U.S. and Ontario and has already beaten some varieties developed for SCN resistance.

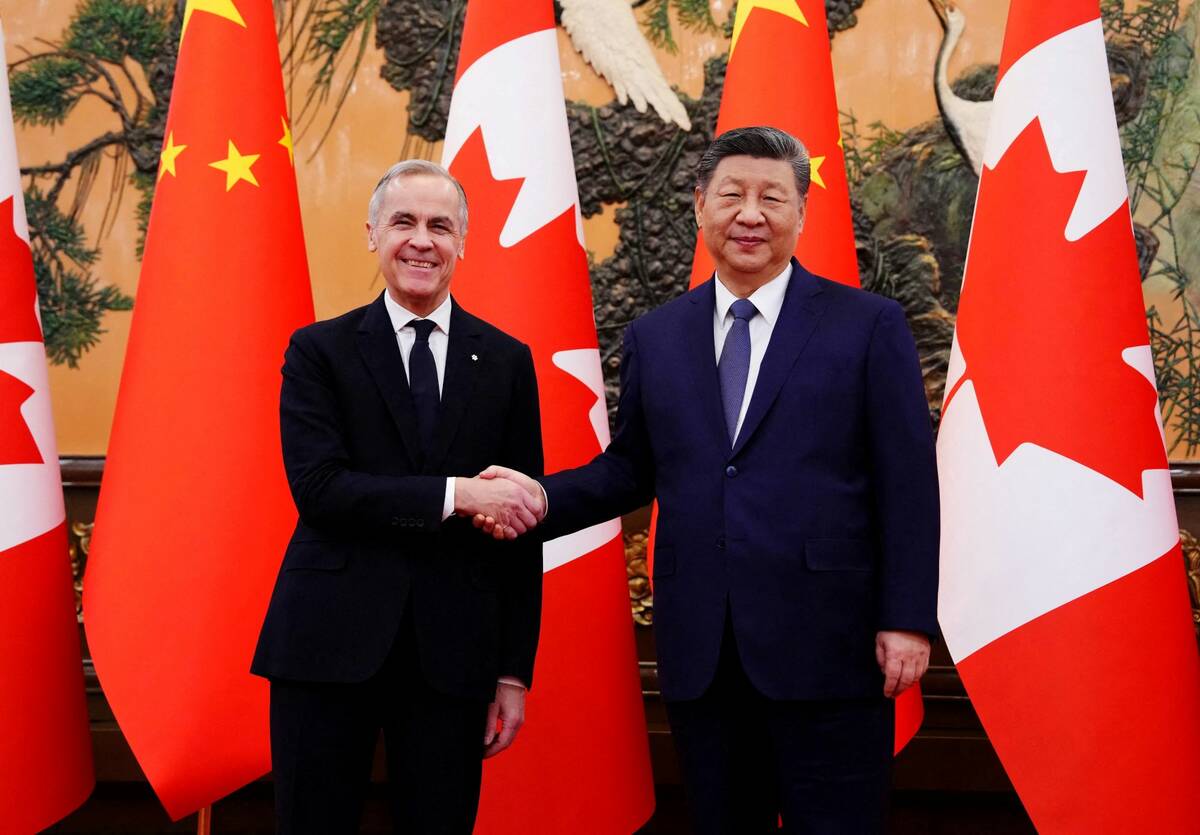

Read Also

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China is a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

A soil-borne roundworm, SCN infects soybean roots and can cause yield losses of up to 30 per cent by the time symptoms are visible to the soy grower. Once it’s taken up residence in a field, it can’t be completely eradicated. Much like with clubroot — the subject of our cover story this week — a farmer’s first defense is to prevent it from ever reaching a field. That means cleaning equipment, vehicles, tools, clothes and shoes before moving on from one field to the next, especially if those items come in from areas where it’s already been detected.

It also means choosing SCN-resistant soybean seed, not to mention rotating through different resistant traits. It also means rotating your fields to include non-host plants, making sure to keep potential host weeds in check.

So, an in-furrow nematicide registered against SCN, such as Mississauga-based Vive Crop Protection now proposes its Averland FC brand could be, would be another significant prong in that multi-pronged approach. Surely a made-in-Canada product would be a boon for Prairie soy growers before SCN gets any further foothold up here, right?

Well, no. This announcement was that Vive is seeking approval — from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — to expand the Averland label for 2026. I optimistically asked whether Vive has a timeline to seek PMRA approval for same, and was quickly informed the company “do(es) not have plans to register Averland FC in Canada.”

This wasn’t a surprise. Our colleague Robert Arnason at The Western Producer has spoken to Vive previously about its current business model, which focuses almost exclusively on the U.S. market. Today Vive has just one product registered in Canada (AZteroid FC, a fungicide for potato crops) compared to seven in the U.S.

It’s not that Vive considers Canada to be small-potatoes, so to speak. Rather, it’s found Canada’s regulatory process increasingly unpredictable and slow. The U.S. path to registration for novel crop tech such as Vive’s is still complex — but is at least clear as to what tests must be done, what information the company must provide and how long the process will take. And other companies and critics have complained that the Canadian process has become more political in nature — so in the interest of being seen to be transparent about the process, it’s now bogged down in what Conservative ag critic John Barlow called “death by consultation.”

By themselves, those concerns aren’t very new, and so far they haven’t forced Vive to haul up stakes and move their entire operation to the U.S. More recently, last fall, federal, provincial and territorial (FPT) government experts’ working group on pesticide management noted there appear to be “regulatory barriers to registering products in Canada that do not exist elsewhere” and that “initiatives to support smaller applicants, such as pre-submission consultations, were not seen as effective in addressing this perception.”

Moreover, the working group “voiced concerns about a growing technology gap in crop protection products between Canada and the U.S. that could put Canadian agriculture producers at a competitive disadvantage in the marketplace” — and “recommends that federal government departments and agencies explore ways to make Canada a more attractive market to register new pest control products, notably biopesticides.”

We’re not suggesting here that Canada adopt a regime of copy-pasting and rubber-stamping U.S. crop protection approvals for the Canadian market. It’s also now possible our neighbour’s administration won’t be as forthcoming on matters of regulatory co-operation and harmonization as we once hoped.

But given Canada’s interest in encouraging new registrations, farmers’ need for diverse chemistries, and crop chem companies’ interest in making money, if not at least more quickly recovering their R&D costs, there’s a case to be made for the regulators and regulated to meet each other halfway — or at least somewhere on a scale between government accepting the value of submissions to U.S. regulators at par, and companies not even bothering to seek Canada’s approval at all.