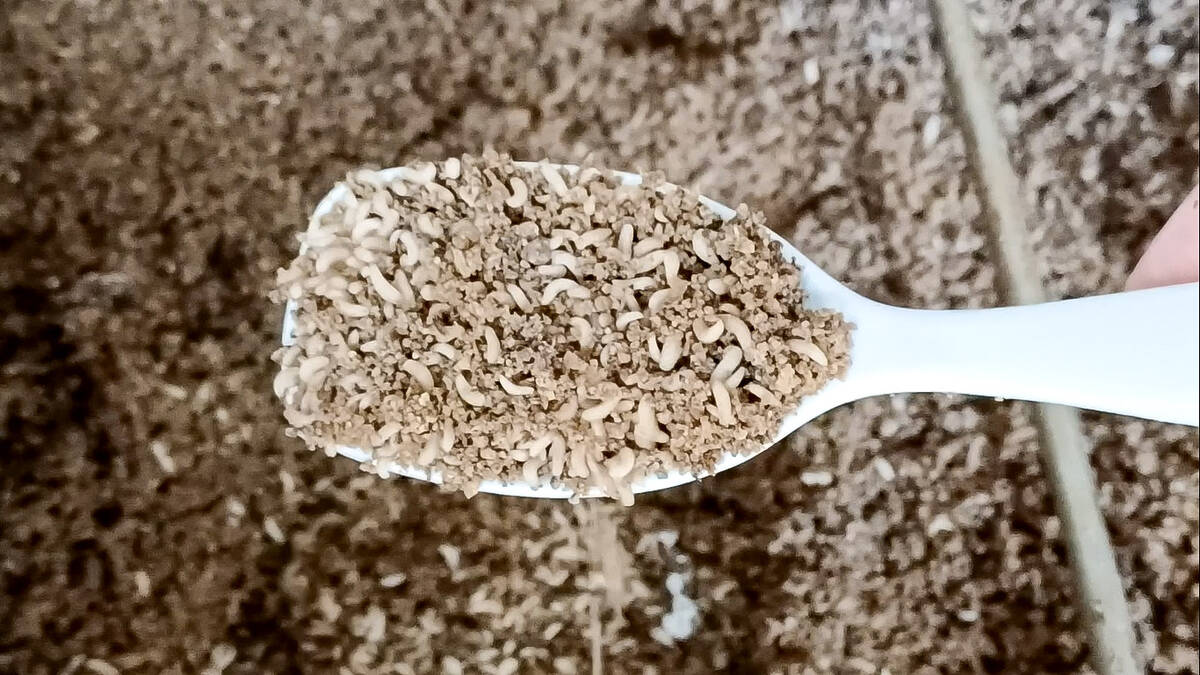

Ynsect, the world’s largest insect farming company, was recently put into receivership. It follows others around the world, including Aspire, an insect farm in London, Ont.

What’s happened to turn a sector with billions of dollars in investment to ruin?

As an alternative protein source, insects sounded good. They consume waste, grow plentifully and have a good protein profile and were thought to have a lower carbon footprint. And no, unlike various commentators have suggested, the politicians weren’t making humans eat them.

Read Also

Cabbage seed pod weevil the surprise top canola pest in Manitoba for 2025

Get set to scout this summer. After a few years of low profile in Manitoba, cabbage seed pod weevil populations, among a few other pests, boomed here in 2025.

Instead, insect farming was aimed at the bottom of the commodity protein market, feeding animals and fish.

A Rabobank AgResearch report in 2021 said that 40 per cent of all insect protein would go to the rapidly growing farmed fish segment. Much of the rest of it would go into pet or livestock feed.

Companies like Aspire, Ynsect and InnoFeed began rapidly scaling around the world, but most didn’t make it through the scaling phase. Insect production at a giant scale is difficult, it turns out.

When announced in 2020, the Aspire Food Group’s cricket plant in London was to be the largest in the world, producing 12,000 tonnes of crickets per year. The company struggled with scaling and never reached full capacity.

In May, Farm Credit Canada and other creditors put the company into receivership.

According to AgFunder, the buildings have been sold to Halali Group Holdings, which may use the facility for insect production again.

Ynsect was growing mealworms, also mostly headed for feed. But it turns out few people have worked with mealworms at a giant scale, and the fatty insects are pretty tough on equipment. There were delays.

Like most livestock, insects do better on an optimized diet. Just feeding them volumes of waste meant inefficient production.

Ynsect had raised about the equivalent of almost $1 billion. It had heavy subsidies from the French government. Despite all the money and research effort, insect protein remained too expensive.

I expect there will be niche insect protein producers who will remain in business, supplying a premium market at a smaller scale.

Maybe at some point the technical barriers will be solved. But the system will be more complicated at billion-cricket scale than the long-proved systems we have of raising poultry, pigs and cattle.

It’s a cautionary tale for lab-grown animal proteins. It’s thought they too will compete at the low end of the protein marketplace, but I expect they will be stuck at the top end of the cost structure.