I’ve done a lot of things with chicken in my life, mostly related to eating. But sharing a bus with one was a first.

When taking the bus in rural Malawi there’s no telling who you might be travelling with.

In a country where few can afford a car and one of the few luxuries is time, buses are how most people travel farther than a bicycle or walking will take them. You don’t just slip into the nearest market town for a bag of maize like we would go for milk. You stand on the roadside waiting to flag down a passing bus with enough room to stop.

Read Also

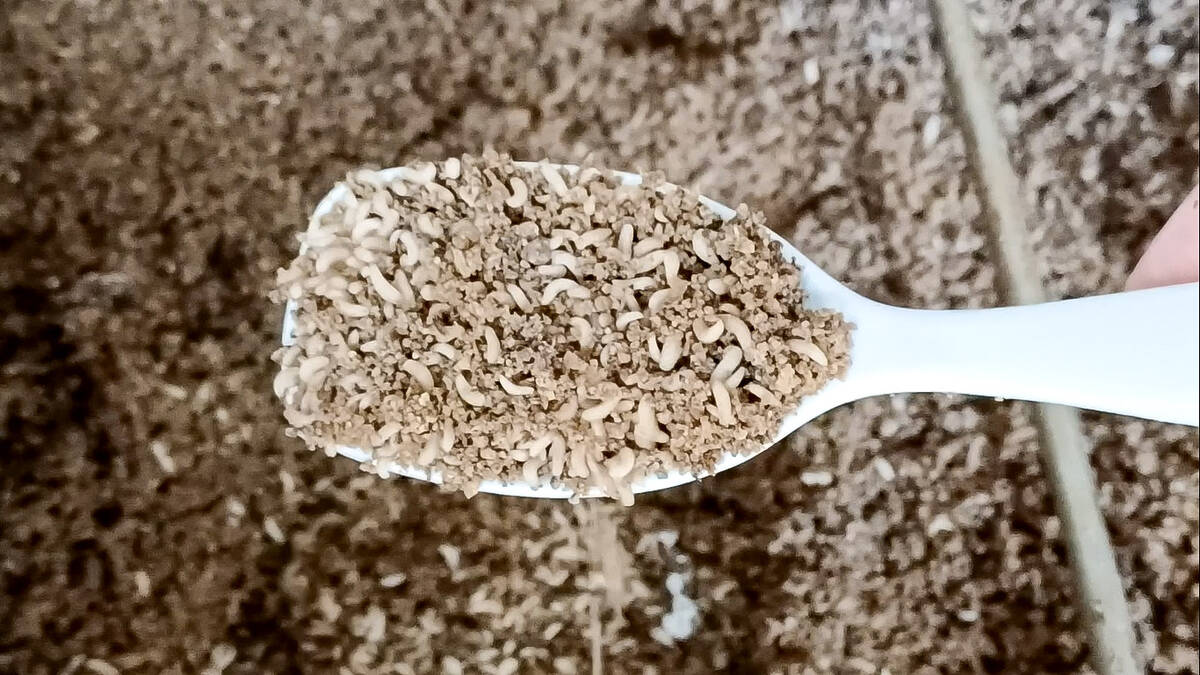

Bug farming has a scaling problem

Why hasn’t bug farming scaled despite huge investment and subsidies? A look at the technical, cost and market realities behind its struggle.

If you don’t mind waiting or sharing your personal space (too bad if you do), it is remarkably efficient and low cost. For under 10,000 Malawian kwacha or about US$20, you can go just about anywhere.

But be warned, local buses here are the antithesis of comfort coaches. Most of them are outdated, poorly maintained, fume-spewing back busters. We’ve hopped aboard several in the days since we left Lilongwe, Malawi’s capital. When we arrived at the bus station/market area, there were several buses headed for the same destination with the drivers raucously competing for passengers.

These so-called “local” buses don’t seem to run on any particular schedule. They leave when they are full — enough. However, in Malawi determining when a bus is full is relative, somewhat akin to asking, “How long is a piece of string?”

The bus we chose looked full enough to us. We boarded and clambered over people and suitcases to the last two open spots. There we sat for another hour in the sweltering humidity as still more people climbed aboard.

We were later told the drivers need a certain number of passengers to start their engines, which is generally one or two more than the available seats. We were also told it takes longer to fill buses during the “lean months” in Malawi, between January and April. For many families, last year’s stored maize has run out and the new crop is not yet ready. People don’t travel as much when they are hungry.

While we waited, vendors roamed up and down the rows of loaded buses carrying the Malawian version of fast food, trays of hard-boiled eggs, bananas, fried dough and cold drinks sloshing around in melting bags of ice.

Finally our bus was full — enough.

A group of men gathered around the back of the bus and started pushing with a rocking motion, before falling back with a cheer when it started to roll forward and the diesel engine sputtered to life. Taxis here are often parked facing downhill to operate on the same principle.

The bus was built for 20. We had 28 on board, not counting the chicken. Except for the occasional squawk, it sat comfortably cradled in its owner’s lap staring out the window like the rest of us as the bus puffed black smoke up the hills and chugged past lush fields of maize and groundnuts and sleek, well-fed cattle and goats.

There is a strange harmony to the chaotic flow along Malawian highways. It should be mayhem with motor vehicles travelling at high speeds whizzing past pedestrians and cyclists transporting everything from people to lumber to sacks of maize and even other bicycles on a ribbon of tarmac barely two lanes wide. Herds of goats, cattle, and yes, even chickens dare to cross, wings flapping and stretched out like, well, roadrunners.

The unspoken rule is that slow movers yield to the blaring horns of bigger, faster vehicles, unless it’s livestock, in which case, everything slows to a crawl.

Two hours later we disembarked in Salima to catch our next bus to Nhkotakota. As we started out with only nine on a 14-seater Toyota van, I thought, mistakenly, we got off easy this time. But my travelling companion warned rather ominously, “They will expect us to put four on this seat.” How right he was.

The driver soon picked up another customer. The Toyota’s sliding door actually popped off its rails at one point, just as passenger 26 climbed aboard. In addition to people and luggage, we were also carrying a bicycle and three bags of maize by then.

I cringed when I saw a man approaching our bus at one stop with a bunch of dead fish hanging on a string. Thankfully, he was selling, and no one bought. On our next bus, however, as we headed farther north into the high country of Mzuzu, we transported a big smelly tub of fish all the way to market.

Six hours after leaving Lilongwe, we pulled into our first night’s stop as the sun was setting, just in time to find lodging and something to eat before turning in for the night, huddled beneath our mosquito nets, and listening to the geckos chirp.