U.S. agricultural imports now exceed exports and the deficit is expected to worsen, according to a study from the University of Illinois.

“For most of recent history, the U.S. was a net agricultural exporter. But in the last couple of years, that has reversed,” said lead author William Ridley in an Oct. 7 news release.

“Current projections estimate that the agricultural trade deficit will reach (US)$49 billion by the end of 2025.”

Read Also

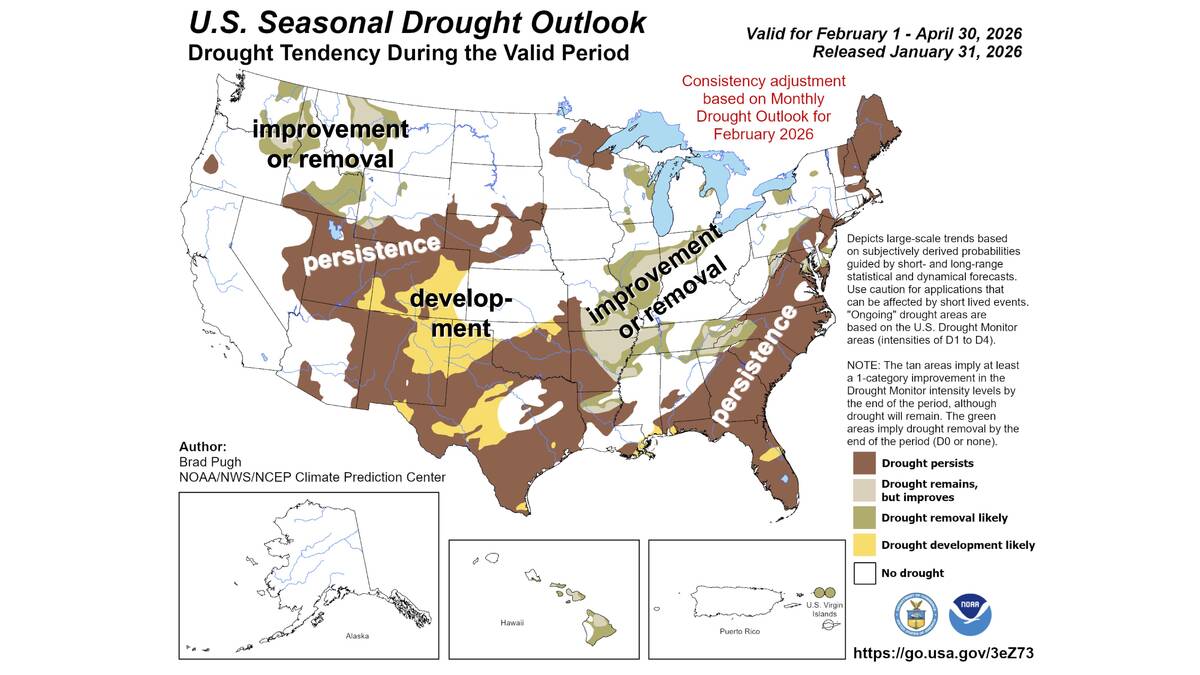

Neutral conditions drive 2026 weather as La Niña subsides

U.S. government meteorologist expects there will be neutral ENSO conditions for the 2026 farm growing season.

WHY IT MATTERS: U.S. trade policy, including agricultural trade, has taken a more adversarial tone since U.S. President Donald Trump took office.

Ridley is an associate professor from the University of Illinois department of agricultural and consumer economics. He conducted the study with Stephen Devadoss, professor of agricultural and applied economics at Texas Tech University.

The study found that the U.S. continues to be a major producer of commodities like corn, soybeans and cotton, but exports are stagnant or declining. Markets are shifting as trade conflicts create uncertainty and instability — case in point, the ongoing trade disputes with China.

2018 trade war fallout

“Arguably, the most impactful events for the U.S. agricultural sector in recent years were the numerous conflicts initiated in 2018,” the study says, “including (but not limited to) the U.S.-China trade war.”

In early 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump approved a series of tariffs on products including solar panels and washing machines that targeted China; and imported steel and aluminum, which covered imports from all countries (Canada included), but heavily affected China.

China retaliated, including levies on U.S. soybeans, corn, wheat, pork and sorghum. Most agricultural exports to China faced tariffs of up to 25 per cent, the report says.

Between 2017 and 2018, U.S.-China soybean export values declined by 73 per cent, or US$9 billion (C$12.6 billion). Wheat exports fell by 67 per cent, or $431.7 million (C$604.3 million). There was a drop of 61 per cent, or $92.6 million (C$129.6 million) for corn. All told, the U.S. lost some $14 billion in agricultural exports.

China reallocated many of its imports to non-U.S. sources. Brazil, Australia and Ukraine are among countries that have expanded more into the Chinese market to fill the gap.

“The Phase One trade deal that was negotiated in 2020 briefly increased Chinese agricultural imports from the U.S., but trade quickly collapsed again,” the news release further said. “China has effectively stopped buying soybeans, corn, cotton, and sorghum from the U.S., after finding trade partners elsewhere.”

Other countries also retaliated against U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs and, while some retaliatory duties were rescinded relatively quickly (as was the case with Canada and Mexico), others lingered. India’s duties on U.S. chickpeas and lentils were only dropped in June 2023.

Compromised competitiveness

Meanwhile, the U.S. is also losing its global competitive edge to other big grain producers like Brazil, Canada, Australia and Ukraine, the study found.

Ridley and Devadoss estimated the comparative advantage of major crop producing countries as part of their research. Factors like productivity growth, export and trade infrastructure, and government support were all weighed.

U.S. agricultural productivity has been relatively stable, they noted, but other countries are catching up.

Brazil’s soybean production has rapidly evolved and it has surpassed the U.S. as the top exporter of soybeans, buoyed in part by large increases in farmland area. Between 2003 and 2023, Brazil’s harvested soybean area grew to 44.4 million hectares (109.7 million acres), up from 18.5 million hectares (45.7 million acres).

U.S. soybean and corn acres marginally increased in that time, the study found, and acres of crops like wheat, barley and sorghum declined.

Brazil’s productivity also improved with soy yields up 22 per cent for soybeans between 2002 and 2022, and corn yields rose by nearly 59 per cent.

“While U.S. yields also increased over the same period, the increases were, with the exception of soybeans, generally smaller than those achieved in Brazil,” the report said.

Brazil’s investment into infrastructure have also paid dividends.

Stalled agricultural productivity has also been a conversation in Canada. In 2023, a Farm Credit Canada study noted that, while growing, the pace of average total factor productivity growth in Canadian agriculture — defined as the combined impact of new technology and improvements to efficiency — had dropped from around two per cent year-over-year in previous decades to 1.4 per cent in the 2010’s. It was expected to further drop to one per cent in the current decade.

Shifting trade

China, meanwhile, has increasingly opted to buy soybeans from Brazil and other South American countries.

This year, as Trump renewed his trade war with China, China has steered clear of U.S. soybeans.

“U.S. row crop exports are trending in a negative direction, and forecasts predict the downward trend will continue,” Ridley said. “Producers may look to other markets, but there’s only one China, and they’re not coming back tomorrow. Even if you pulled these tariffs back right now, sales would not resume. And other markets have barriers to trade; for example, the EU has tight restrictions on imports of genetically modified crops.”

Other factors that have eroded U.S. agricultural trade include lack of recent progress in securing new trade concessions in import markets and changing dynamics in trade between other countries, the researchers said.

For example, in 2023, Brazil and China agreed to cut out the exchange role played by the U.S. dollar and conduct trade in their respective currencies (the Chinese yuan and Brazilian real).

“The de-dollarization of the $150 billion Brazil–China trading relationship promises to further strengthen the countries’ economic ties, which is likely to have ramifications for U.S.–China exports,” the report said.

Also, since the Trump administration abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement in 2017, the U.S. hasn’t done much to secure new trade deals—aside, perhaps, from the Trump administration’s tariff negotiations in the past year.

By contrast, other other countries in Trans-Pacific Partnership (including Canada) went on to form the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), to the general welcome of export-reliant Canadian farm groups.

Canada’s subsequent wheat exports to CPTPP countries increased to $5.4 billion (C$7.58 billion) from $3.8 billion between 2017 and 2023, and Canada’s governments have tagged the region for potential agri-food trade expansion. Meanwhile, U.S. wheat exports to CPTPP countries fell to $3.3 billion from $4.6 billion.