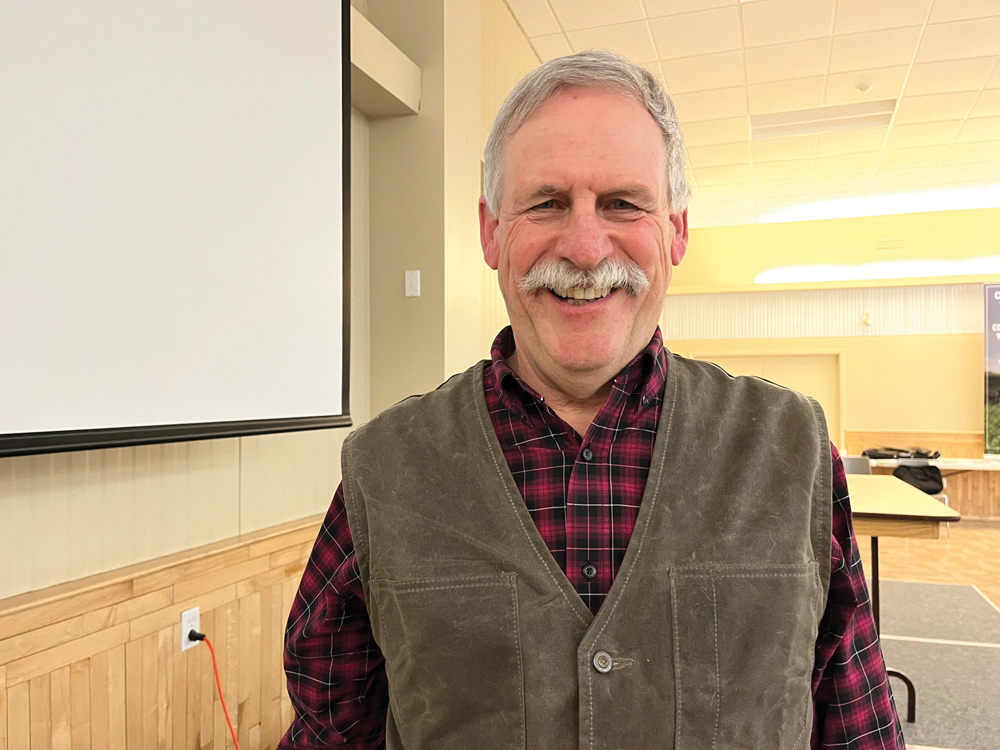

Michael Thiele wants farmers to design their cover crops for whatever they don’t have in their system.

The soil health presenter said during an early January workshop in Minnedosa that for some farmers, that might be soil carbon. For others, it might be nitrogen or soil structure or other soil health traits.

On the business end of things, it’s about making money or feeding cattle. Whatever the priority, a farm-specific plan and thoughtful species mix should be a cornerstone of the practice, said Thiele.

Read Also

Manitoba sunflower plant gets local owners

Scoular’s sunflower and bird feed plant in Winkler, Man., bought by Orenda Commodity Services Ltd. out of Ste. Agathe.

Why it matters: Experts say a deliberate cover crop plan is often the difference between reaping the purported benefits and walking away in disappointment.

A successful mix should check off a range of boxes, including biodiversity. Thiele is a vocal advocate of pushing biodiversity, arguing that it contributes to long-term resilience and profitability of the farm.

“You need two spreadsheets, one that keeps track of money, which is a thing, of course. But you also maybe need to keep a sheet — much harder to put numbers to — that has all the other stuff, like soil biology or organic matter or water infiltration, that may not pay off this year, but may pay off next year.”

Thiele said profit is the main driver among those he knows who have embraced regenerative agriculture and biodiversity practices.

Too diverse?

Bart Lardner, professor and applied researcher in beef and forage systems with the University of Saskatchewan, is less enamoured with cover crop mix lists that might include 15 species or more.

“If you’ve got 12 species in there, I need to justify the characteristics of each species and how it’s going to benefit you,” he said. “Is it going to fix N (nitrogen)? Is it yield for my animals to graze? Maybe it’s a good rooting system. Is it going to germinate? All of these things. And what level (of each) am I going to have?”

Maturity rates are another factor. Lardner said a three or four species mix is easier to time for feed utilization than a more complex blend.

His work has involved cover crops in one way or another since the 1990s, although back then, the practice was more about suppressing weed pressure and gleaning return during the first year of perennial forage establishment.

His cover crop work has been focused through the lens of grazing and forage rather than crops, first through the Western Beef Development Centre and more recently at that site’s successor, the Livestock and Forage Centre of Excellence.

In one such project, Lardner compared an annual forage system of straight barley with a mix of forage peas, hairy vetch, crimson clover, Italian ryegrass, sorghum, millet, turnip and turnip kale over two years in 2017-18.

The straight cereal crop yielded about 20 more feed days per acre and cost about $38 an acre less, which Lardner linked partially to weed control limitations in the polycrop. Cattle used more of the barley in a winter grazing situation.

Digging down

Beneath the soil, it was a different story. Root biomass in the polycrop far outstripped the barley acres, thanks to the mix of different species with different rooting depths and traits, said Lardner.

That affected soil carbon levels by the end of the trial. Soil tests taken from upslope parts of the field, in particular, showed a decrease in total soil organic carbon in the top 20 centimetres of soil where straight barley was grown. Polycrop plots showed increases from around two megagrams per hectare (the top five cm) to eight (from five to 20 cm down).

The polycrop also beat the barley’s carbon test results downslope at deeper depths, although to a lesser degree. All systems at all depths saw at least some carbon gain in downslope samples.

Lardner said there is opportunity to increase short-term soil carbon with polycropping, particularly in low carbon areas, although producers would have to consider the cost trade-offs.

“If you’re putting a legume in there, put a hardy legume that’s going to do some nitrogen fixation. Put a pulse in there, it’s going to give you some good protein, put that cereal in there at whatever level you can justify for oats and barley,” he said.

“But to me…if I’m going to maybe have to lose a little money grazing cover crop compared to my conventional oat swath graze program, I need to make up the difference.”

That might be where funding programs come in.

Topping it off

Public dollars have been earmarked to push cover crop integration at the farm level. Manitoba’s iteration of the outgoing Canadian Agricultural Partnership included cover crop establishment on the list of cost-shared beneficial management practices.

Likewise, the practice is among the pillars of the Prairie Watersheds Climate Program now administered by the Manitoba Association of Watersheds through to 2024. Practices to reduce nitrogen fertilizer use and improve grazing management are also covered under that program.

Those programs have a role in covering farmer risk that might otherwise curb interest in the practice, Thiele said.

‘Be smart’

In other cover crop philosophies, a long species list is an easy way to hedge against a wreck.

Mixtures of warm and cool season crops, or those that belong to the same classification but prefer different growing conditions (such as a dry-loving and a moisture-loving pulse), have been cited by cover crop advocates as a means to ensure a robust stand regardless of season.

“You have to be smart about it,” Thiele said. “Don’t blow the budget to have this super diverse mix and not really get a return for it… but we know that there’s power in diversity. To argue over whether it’s three or four or 15 (species), I guess I’m thinking it’s not really a useful argument.”

Instead, on-farm testing will be more useful in determining the best practice for that individual farmer, Thiele said. The other part of success is education.

A farm already heavy on canola in the rotation, for example, should go easy on brassicas in the cover crop. Lardner gave the same advice, citing potential feed quality concerns for grazing.

Thiele said a silage mix can have a multitude of diversity while still short-changing the producer on cover crop benefits. He used the example of a multi-species mix that contained mostly grasses and was notably short on nitrogen-fixing potential.

Having too much oat or other competitive crop that overwhelms the rest of the mix is another potential pitfall.

“There are details,” he said. “You go out and you’re going to do a cover crop and then you don’t really think it through and throw it in the ground and you’re unhappy with it. You can’t blame the cover crop. Understanding is important.”