It’s been a different time for the Manitoba Association of Watersheds.

The organization, whose network of 14 districts is only four years past its transition from the former conservation district system, is used to running conservation and water management projects.

But it recently branched into being the vehicle for government programs, many of which come with a distinct agricultural flavour.

Read Also

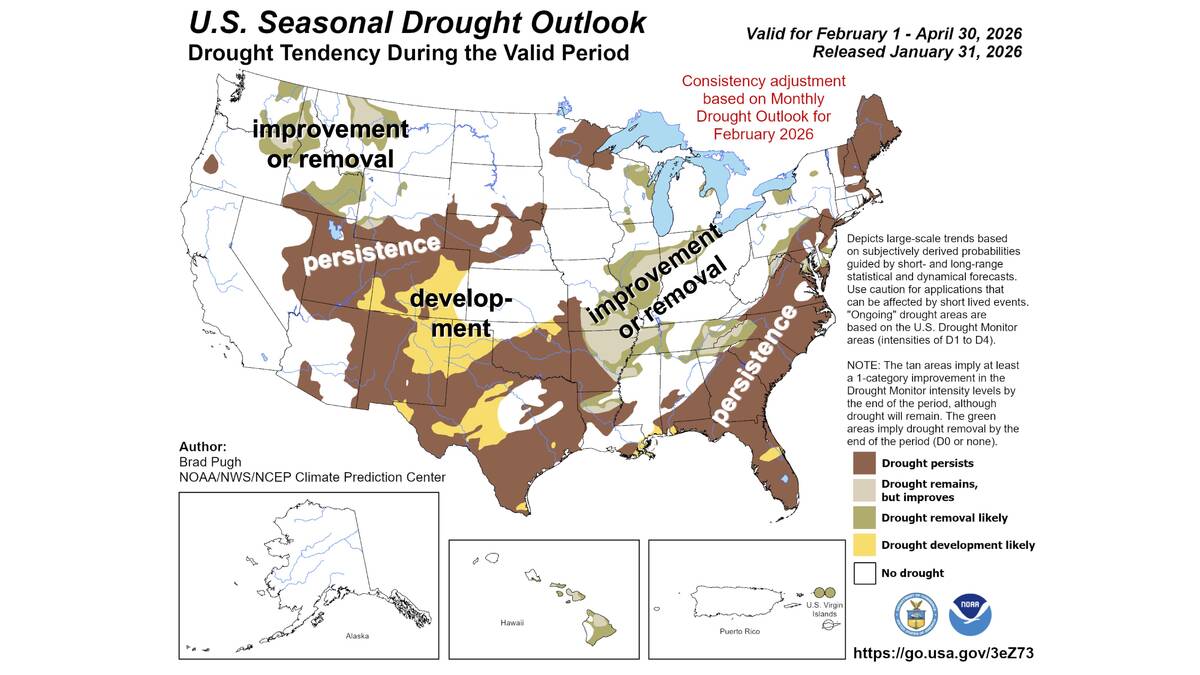

Neutral conditions drive 2026 weather as La Niña subsides

U.S. government meteorologist expects there will be neutral ENSO conditions for the 2026 farm growing season.

“There was always talk about funding and funding watershed districts, but what we’re doing now is we’re working as a delivery agent for government programs,” said MAW chair Garry Wasylowski.

“So, it is a different step. But what we’ve done as an organization, as individual watershed districts, is that we’ve stepped up our programming, stepped up our staffing.”

Why it matters: The shift to delivering specific government programs rather than operating under general funding has been a learning experience for Manitoba’s watershed districts.

In 2022, the association was selected by the federal government to deliver the Prairie Climate Watersheds Program (PCWP) in both Manitoba and Saskatchewan. That program, offered under the umbrella of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s On-Farm Climate Action Fund, came with up to $40 million and is slated to run between February 2022 and the end of March next year.

The idea was to fund farm-specific projects that aligned with three broad categories of beneficial management practice, all with the goal of sustainability and emissions reduction.

Farmers could, for example, get funding to buy into rotational grazing, which might involve new fencing or watering systems, the costs of creating a grazing plan or adding legumes to pasture.

Cover cropping included things like establishing cover crops in the spring or fall shoulder seasons, planting a full-season or perennial cover, or planning and assessment costs.

A third stream, nitrogen management, covered a long list of practices ranging from the cost of soil mapping and testing to adding legumes, updating equipment for lower-loss application and incorporation, opting for split application or switching to options like polymer coated urea, added inhibitors or manure/compost.

Speaking at the Manitoba Forage and Grassland Association’s regenerative agriculture conference in Brandon in November, MAW program manager Dan Cox noted that nitrogen management projects were particularly popular.

Cox said the program handed out $15.6 million to farmers across both provinces in its first year. A total 1,411 farmers participated. In Manitoba, 731 farmers got projects funded, to the tune of $7.46 million.

Cox further noted that some districts are already creating waiting lists for the next round of funding. Manitoba’s portion for 2023-2024 is expected to grow to $9.8 million, while MAW expects that it will hand out $19.7 million between Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

“What it does is it shows government that we are capable of delivering other programs for them,” Wasylowski said. “I see that as the way that we are going to go.”

PCWP has also been a bridge between the watershed districts and producers, representatives from some districts said during MAW’s conference in Brandon in early December.

Conservation districts and, later, watershed districts, have not always been popular with farmers, who may resent the perceived criticism of their practices or worry about clashes between conservation and agricultural priorities.

“I used to say that the watershed districts were the best kept secret in Manitoba,” Wasylowski said. “Certainly this program has gotten us better known.”

PCWP funds are not the only government dollars MAW members distribute. The association delivers funds from the province’s GROW Trust, established in 2020 to set out conservation funding “in perpetuity” and available in those areas covered by a watershed district.

That trust is administered by the Manitoba Habitat Conservancy.

MAW has also been one of the driving partners in the now wrapped up Living Labs Eastern Prairies initiative, which looked to bring together producers, researchers and other stakeholders to test novel ag practices.

The successor to that initiative, Living Labs Manitoba, was announced Nov. 15 and has been earmarked for $9.2 million in funding over the next five years.

That initiative “will develop and test BMPs [beneficial management practices] for nutrient management, natural and agricultural landscapes, water retention, agroforestry, crop and livestock integration, grazing management, rhizome microbiome, soil organic matter growth and soil health, as well as facilitating better use of resources,” according to AAFC.

MAW will play a major part in the development and roll out of the initiative.