Regenerative agriculture has spent years digging roots into the mainstream for farmers. Champions and policy makers have touted it as a win-win for the industry: good for the environment, good for carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions, good for land productivity, good for livestock producers who raise their public image — done properly, good for the farmer’s profit.

For Indigenous farmers though, the relatively new regenerative agriculture movement looks a lot like old knowledge.

WHY IT MATTERS: Many lessons being pushed at grazing workshops and regenerative agriculture events dovetail with traditional Indigenous goals for land management.

Read Also

Ship’s turning for gene-edited crops

More and more countries have decided that gene-edited crops will be treated the same as conventional plant breeding.

Like mainstream regenerative agriculture, Indigenous traditions prioritize learning from and working with natural cycles. Intercropping is a long-held food tradition, as is keeping large ruminants on grasslands.

“Regenerative agriculture is kind of a new term,” said Jennifer Bogdan, project agronomist at Bridge to Land Water Sky Living Lab at the Indigenous Farm and Food Fest at Batoche, Sask., earlier this year.

“So, it’s not really a system. It’s more just an approach to farming, and more of a holistic view, and it really focuses on soil health, and with the objective of, if you can improve the soil, then there are many other benefits that will follow.”

She listed improvements to things like biodiversity, water management and infiltration, organic matter and air quality.

Today, there are funding programs listing those practices and goals in the same breath as farm resiliency — being better able to absorb adverse weather conditions such as drought or flooding with less financial crisis — and overall farm profitability through reduced input cost, greater productivity and (although still in progress) the potential for market premiums.

Adding on regenerative agriculture

Bogdan believes many farmers are already incorporating regenerative ag practices and it wouldn’t be difficult to branch out further and incorporate more. Some are more common than others, like minimum tillage, variable rate fertilizer and bale grazing, while others are less adopted like:

- intercropping;

- cover crops;

- livestock integration;

- leaving pollinator areas; and

- respecting riparian and marginal areas.

Melissa Arcand, an associate professor in soil science and instructor in the Kanawayihetaytan Askiy program at the University of Saskatchewan, likened these practices as a “full circle conversation”. Many of them are not Indigenous practices themselves, but they connect to Indigenous cultural and agricultural ideas like listening to the land, having balance with the land, and having plants help each other.

“I think the modern regenerative ag movement takes a lot of principles that probably emerged out of what we’d consider to have been traditional agriculture and even traditional ecological knowledge,” she said.

Arcand added that these principles can be integrated in small scale or large scale operations to mitigate native plant loss, improve diversity, and benefit producers.

Full-scale farming practices

While there is more ease in adopting these ideas at a small scale, Arcand views adoption as a broad spectrum seeing small-scale, fully regenerative on one end and large-scale commercial and conventional on the other with the ability to find a balance so operations can blend concepts.

“These sort of ecological relationships can help to improve overall,” she said.

“Like, not only productivity in terms of yield output, but also like efficiency of using of resources and improvements towards ecological and environmental outcomes so can we mitigate the risk of runoff that causes eutrophication because of too much nutrient loading.”

In the discussion of regenerative practices, Bogdan gave the example of unproductive, marginal land equating it to an open cow or poorly laying chicken, saying those animals wouldn’t be kept so why keep farming that saline corner of a field?

“You’re putting so many dollars per acre of inputs in there, and still, you’re not going to be able to harvest a crop out of it.”

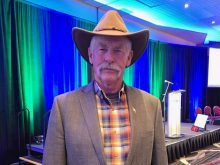

Tom Harrison, a rancher and member of the Saskatchewan Stock Growers Foundation, shared the perspective of the livestock sector, saying ideas of diversity are generally more accepted in the livestock world and that there is more of a “work with what you have” approach.

“They work with diversity,” he said. “They work with making sure that their pastures have multiple species of grass in there. You know, basically (staying) green all year long. They work on margins, which means that it’s kind of low input. Manage your margin and look at how to lower your inputs into that.”

To blend practices, he suggested the strategy of cattle and grain producers forming a partnership. There is benefit for the land and for operation improvement, and the partnership combats the recognized challenge of diversifying and becoming a mixed farm today.

Making connections

Using what you have is a main principle, Arcand said.

She gave the example of analyzing crop land, seeing marginal areas, and converting it back to grasses and forages. While it’s not necessarily an Indigenous practice in and of itself, knowledge and reading the land is.

“It’s kind of a principle of knowing and understanding that the land is telling us what it can do, rather than to kind of force it to do something and bend to our will,” she said. “Working with what the land is able to provide and respecting that, at least in principle, is very much a sort of Indigenous or Cree way of thinking.”

Another key idea is intercropping and companion cropping, with the traditional ‘three sisters’ system.

That refers to corn, beans, and squash that when planted in the traditional fashion, they compliment and assist each other as they grow. Corn provides a pole for beans to grow on, beans are a nitrogen fixer and squash retains moisture as a ground cover.

But this idea can transfer to commercial crops, as is seen with pairings like peas and canola or oats.

“Those same sorts of benefits can apply where there’s this sort of synergistic use of resources,” Arcand said.

It can also apply to varying root depths with different plants as they tap in to different levels of nutrients, resources, and moisture, that can be pulled up for their sister plant.

Growing knowledge

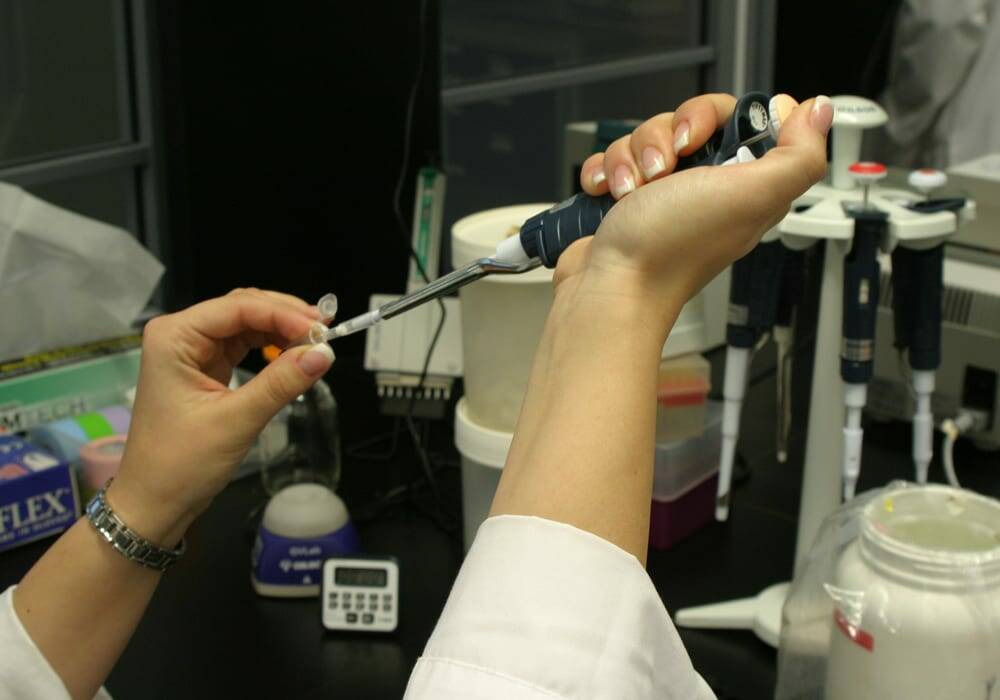

In recent decades, these concepts have been studied to identify what further benefits practices like intercrops, respecting biodiversity zones, and livestock integration can bring to the table. These are ideas that were understood and utilized for generations, but were lost along the way. Now, the science is catching up.

Projects at the University of Saskatchewan, University of Manitoba, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada are diving into work like corn-forage intercrops for grazing and cover crop benefits on grain land. And as ideas are trialled and become science-backed, more farmers are willing to give them a try. Like Lance Walker, a grain farmer near Borden, Sask. who integrated livestock to his operation and has seen improvement to the land like better water retention and reduction of synthetic fertilizer use.

“We’re just now applying other tools to advance it more quickly, or to be more selective,” said Arcand on the research. “But the actual like, doing of the thing, those practices may have been around for centuries, millennia.”