After a brutal few months of being unable to meet the shipping demands of grain companies, the two major railways have largely caught up.

“Over the last two or three weeks, it’s got a little bit better,” said Mark Hemmes, of Quorum Corp., Canada’s grain monitor.

“We probably have less grain left to ship now, than I can ever remember having left to ship this time of year,” he said.

The StatsCan stocks estimate for March 31 was just over 12 million tonnes.

Read Also

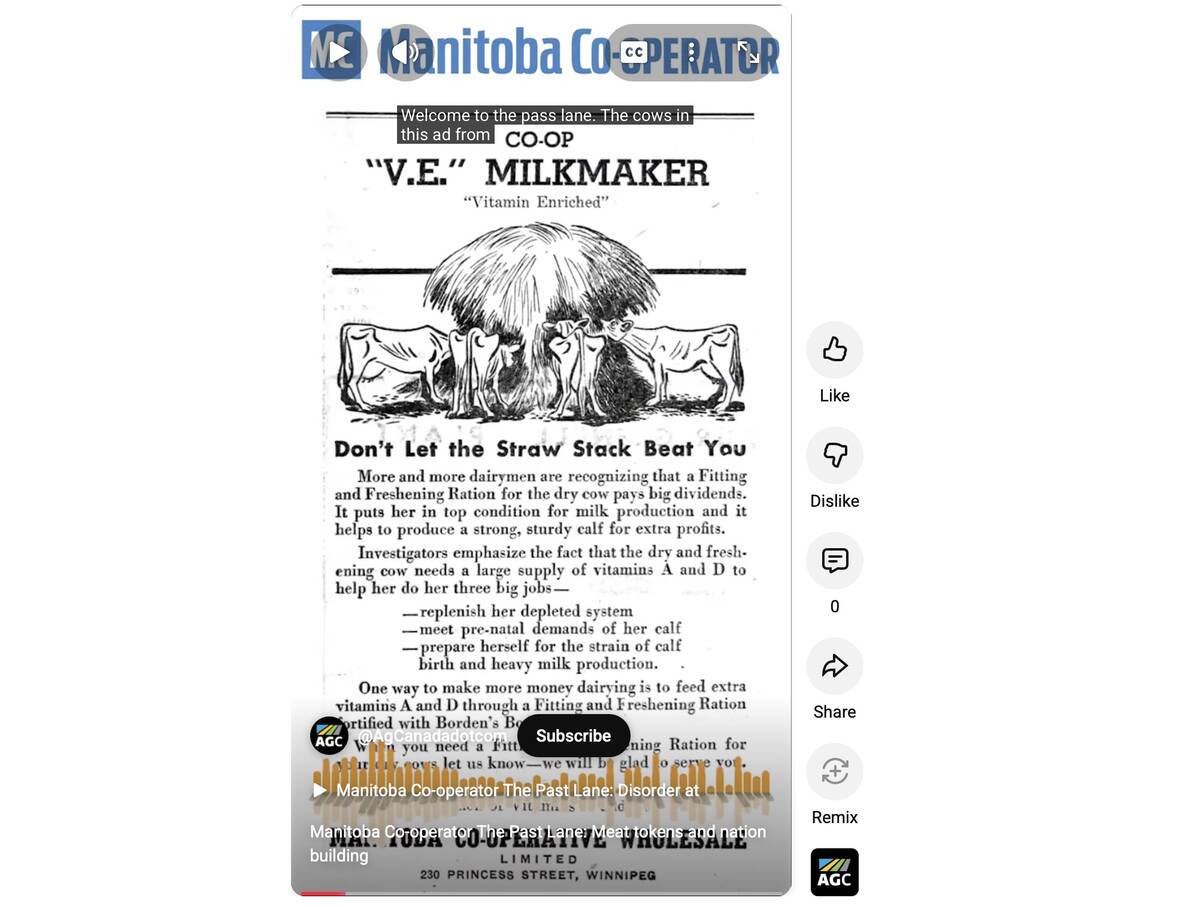

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

“Normally, at this time of year, we’d probably have almost 30 million tonnes,” Hemmes said. “Given the late seeding that’s ultimately going to happen, whatever crop comes off this year, we’re not going to see it until September, so this volume of grain has basically got to keep us going until the end of August.”

While Hemmes doesn’t expect there will be any problems with moving the grain that’s left to move, he’s not saying the crisis is over.

“If we have what equates to a normal crop this fall, there are a lot of people concerned that the railways won’t be prepared to move it,” he said. “And I think that the people have got a right to be concerned.”

Grain shippers say the recent transport backlog isn’t a passing thing, but emblematic of a systemic shortfall.

The problem, says Hemmes, is that the situation on the ground is unprecedented, so it’s very difficult to speculate.

“I’ve been in this business for 45 years. I’ve been doing this job as a grain monitor for the last 21 or 22 years. There is nothing that matches what we’re going through this year. So comparing this to something else – there’s just no point in it.”

One of the issues that is thought to have exacerbated the situation was that CN laid off workers in anticipation of last year’s small crop. And to date, CN hasn’t talked about this issue.

“Everybody knows that there’s an issue with rail service. Everybody is vocalizing that concern, and while CP has been a lot more up front about what it plans to do and how it’s dealing with it, we haven’t heard anything from CN yet,” Hemmes said.

For their part, while they didn’t comment specifically on the layoffs, in an emailed statement, CN indicated it is gearing up for business as usual for the 2022-23 grain year.

“In CN’s latest quarterly results call, our executive leadership reiterated their commitment to moving grain as well as the importance of being ready for a return to normal crop production levels. Our 2022-23 grain plan will reflect that commitment and provide details about how we will move that crop,” their statement read.

Wade Sobkowich, executive director of the Western Grain Elevator Association (WGEA) is skeptical, pointing out that CN’s grain plan last year said that they would provide 5,350 rail cars per week. Shipper demand for the week of February 13 to 20 was only 1,240 rail cars.

“CN provided in that week just 550 rail cars — just a fraction of what CN said it was going to do,” Sobkowich said.

While the details of the rail companies’ 2022–23 grain plans remain to be seen, Hemmes thinks the problem could be too big for the rail companies to recover from.

“The global container system is totally out of sync. It’s lost its ability to have a consistent cycle,” he said.

The problem for the railways, as Hemmes explains it, is that there is a fixed number of container rail cars in the North American fleet.

“So what each railway had at the beginning of 2020 is what they’ve got now. So what they’re trying to do is move a phenomenally higher volume of containers with the same resources that they had in 2020, and that’s problematic,” says Hemmes. “The only way that they can achieve that additional capacity is by moving faster. And everything that’s happened to the railway since November basically flies in the face of any kind of attempt that they can make to move faster. And that’s largely why we’re not digging out of this.”

From Sobkowich’s perspective, he thinks the problem is baked into the system.

The WGEA wrote the Canadian Transportation Agency (CTA) in March and told the regulator that the issues that grain shippers have been experiencing are systemic.

“If this was a normal year from across volume point of view, it would have been an absolute catastrophe,” Sobkowich said. “So what does that mean for the fall? What does that mean for next winter? And so we asked (the CTA) to do what is called an ‘own motion investigation’ which is the agency’s ability to take it upon itself to investigate systemic issues. The agency declined to do that. So, we’re not sure what the next step is here.”

But Sobkowich does know that if the problem isn’t addressed, it will be a disaster.

“We’re looking at severe costs, reputational damage to the grain industry and in our inability to deliver on sales made during the peak price periods, which is in the fall and winter.”

To a great extent, Sobkowich says the railways aren’t to blame.

“The railways are only behaving in a predictable way under the current regulatory and competitive environment,” he said. And because of the nature of the grain industry, farmers are more negatively affected by this regulatory environment than other sectors.

“If you’re a coal mine and you’re not getting good rail service, you can turn back the taps on production,” Sobkowich said. “When you turn back the taps on production that represents less potential volume. So there’s a threat of loss of business for a railway.” In the grain industry, the producer of the grain and the shipper of the grain are different parties. Farmers are the producers and they grow a crop every year and that crop sits and waits to be moved.

“It’s not as though we can turn back the taps of production,” Sobkowich said. “The railways know that and they know that, that crop is there and they will get to it eventually. And so they can put us at the back of the line when it comes to setting shipping priority.”

In the end Sobkowich said it amounts to shippers fighting over the size of pie pieces from a pie that’s too small.

“The railways should be obligated to put on enough capacity so that all sectors that require shipping get what they need,” he said.

However, any systemic changes appear to be somewhere in the distant future. And for now, the situation is tenuous.

“As farmers head out into the fields and they’re starting their seeding right now, one has to wonder what we’re going to be looking at when it comes to the fall,” Hemmes said. “Will the railways have enough people back in position in order to man trains and get the capacity back to where it was two years ago?”