Fertilizer prices have fallen significantly from their highs a year ago — but there is still a lot of uncertainty in the market.

Josh Linville, vice president of fertilizer for StoneX Group, said many market forces brought agriculture to this precarious spot. He traces it back to August 2020, when a high-intensity wind storm hit the United States’ Midwest. Corn prices began to skyrocket after that storm.

Read Also

MANITOBA AG DAYS: Unmoved China tariffs worrying for Manitoba pork

Manitoba pork producers and Agriculture Minister Ron Kostyshyn have both noted lack of progress on Chinese tariffs on pork.

“Our demand for fertilizer went from non-existent to phenomenal; it was the biggest single turnaround we have seen in the history of fertilizer,” said Linville.

Then, in February 2021, there was a cold snap in Texas that saw natural gas prices shoot up, causing fertilizer manufacturers to shut down production and sell their contracts back to the open market.

“Inventories were already tight and got tighter just before spring,” said Linville.

Then, in August of the same year, Hurricane Ida hit the Gulf Coast as the most powerful Category 4 hurricane since Katrina.

“Fortunately, we didn’t see the devastation we had with Katrina,” said Linville, “but it wiped out the electrical grid.”

The nitrogen plants in the area were unscathed, but without electricity, no one was producing fertilizer. So, inventories got tighter still.

In February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. Russia was economically shunned.

“We had lost one of the most important fertilizer exporters in the world as far as phosphate, potash and nitrogen,” said Linville. This once again forced prices up.

Expectations for the upcoming crop were high in early 2022.

“Heading into spring, we were expecting a tremendous amount of demand across all products,” said Linville. The US was expecting to plant 95 million acres of corn. And that’s when the fertilizer markets reached their record highs in (March–April).

But this was also when the wheels started to fall off.

“We didn’t plant 95 million acres,” said Linville. “I think the final number that came out was 88.6 because of the terrible weather situation.”

Demand went down even further when it became clear that Russia’s fertilizer wasn’t off the market at all. While Canada did put a tariff on Russian fertilizer, they were pretty much alone. Russia offered a guaranteed supply at a discount, and many nations took them up on their offer.

“Everyone else said, ‘Morals aside, I’ll take the money,’” said Linville. “And Russian exports were phenomenal.”

But that wasn’t the end of the story.

“European natural gas all of a sudden became the big thing,” said Linville. “Russia started saying if you’re going to continue to support (Ukraine), we are going to back off our natural gas shipments.”

Natural gas prices, which were normally $5–$6 per BTU, had risen to more than $100 by August.

“You cannot produce fertilizer to make money at those values,” said Linville. “European fertilizer production dropped to between 15 and 30 per cent of capacity.”

Then, in September, the sabotage of the Nord Stream pipeline from Russia to Germany solidified the natural gas shortage. It’s hard to repair it, so that continues to put pressure on European prices.

But the EU began shopping for other natural gas suppliers, and as those new sources reached its shores, the price started coming down. Europe also had a relatively mild winter.

“This has brought a significant proportion of EU fertilizer production back on line and is a big reason we’re seeing nitrogen prices fall to where they are today,” says Linville.

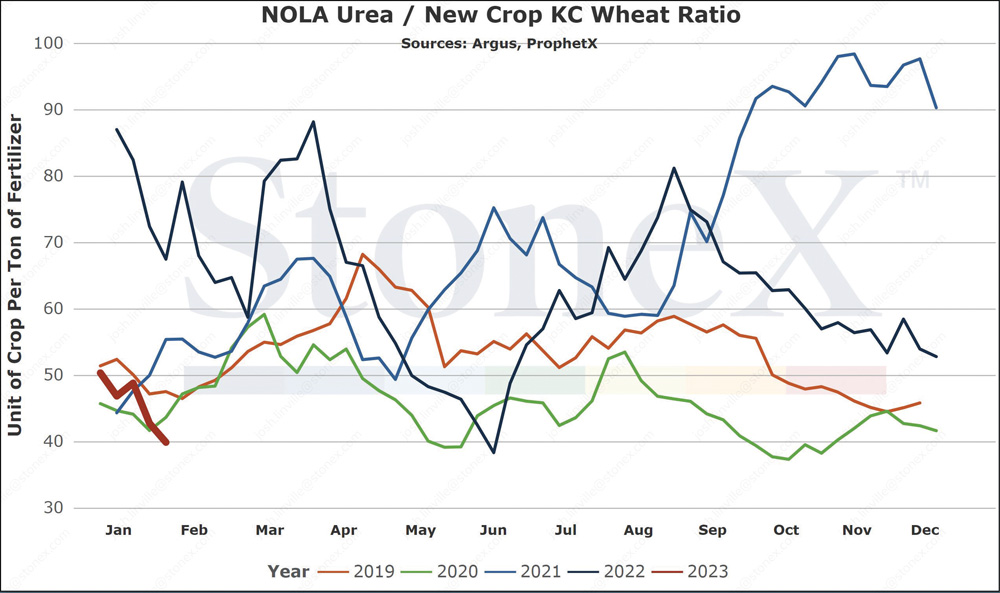

Linville says that in order to navigate through these volatile times, farmers need to shift the way they look at the price of their fertilizer inputs.

“Farming is no more than manufacturing, and we make it overly complicated,” he explains.

“I don’t care if you’re making widgets, iPads, shirts, or whatever, a manufacturer is looking at two things: what are the costs of my inputs and what are the costs of my goods?”

Linville adds that farmers should look at their production similarly.

“I know the flat price is going to lie to me; that’s the emotional pull,” said Linville. Instead of looking solely at the price of grain or inputs, he considers how many bushels of grain pay for one tonne of fertilizer.

Using the ratio of bushels per tonne of fertilizer, a farmer can see the bottom line more clearly. So, even if fertilizer prices remain high and commodity prices also remain high, a reasonable profit can still be made.

To illustrate this, Linville points to the current price of corn and compares using urea (currently the cheapest form of nitrogen available to farmers) at different times over the past year.

“Would you rather spend 140 bushels of your hard-earned, produced corn to pay for one ton of urea (the current ratio)? Or would you rather spend 50-55 bushels (the ratio one year earlier)?”

That “ratio” can also be used to compare different fertilizer options.

So, that’s where the sector is today. What does the future hold?

Linville said the dip in demand was expected and it was clear the high prices from a year ago couldn’t hold, but he says he’s surprised that demand hasn’t come back on line yet.

Speaking in late January, he said that he hadn’t anticipated getting that far through the winter without demand having begun to assert itself again.

Linville said he thinks buyers are holding off to see how low the market will go.

“For the first time since the summer of 2020, buyers smell blood in the water, and they like it,” Linville said. “The buyer finally has some power at the negotiation table, and they want their pound of flesh.”

But unless there’s another horrible spring like last year, demand will come back.

Linville broke down the market forces farmers should keep an eye on that could impact the major fertilizer input prices (urea, UAN, anhydrous, phosphate and potash) in the near future.

Urea

“If European production continues to suffer or even drops more than where it is today, prices are going up,” Linville said. He also said that if urea starts to see more demand because it’s so cheap compared to other inputs, that demand could also drive prices up.

“The flipside is if European production continues to rise and natural gas prices continue to fall, it’s going to scare every trader in the world, and they will want to sell,” Linville said. “The more China and Russia continue to push out product, the lower the prices go,” he said.

“On the bullish side, if European production falters and North American producers sold farther into the future than we think, prices are going up,” said Linville. Another factor that could raise prices is if the expected drop in demand from buyers switching to cheaper urea doesn’t materialize.

Of course, if that demand does drop as expected or even more, prices will drop. Similarly, if Europe ramps up production, prices will drop. Linville said he expects there could be some carryover inventory from last year that could also weaken demand.

Anhydrous ammonia

Linville said he’s fairly bearish on anhydrous ammonia. He doesn’t expect European production to falter. And the expected recession on the horizon will cut industrial demand for the product. And prices could be driven down even further if Russian exports are allowed to return.

Phosphates

The biggest factor affecting the price of phosphates will be whether the Chinese government stops exports again (prices rise), or if they continue to gain steam (prices drop). Also, if the ratio of bushels per tonne of phosphate improves, demand could rise.

Potash

Since early April 2022, potash prices have been in free fall. So the question is when they’ll hit rock bottom. Belarus is the second-largest producer of potash (Canada is the first), and exports from the landlocked nation were blocked by Lithuania when Russia invaded Ukraine. While he said it’s unlikely, should Lithuania reopen that Baltic trade route, it could lower prices further. But Linville thinks demand is improving because of the ratio of bushels of grain per tonne of product, and if Belarus remains off-line, prices could begin to rise again.