Digital agriculture. Precision agriculture. Smart agriculture. E-agriculture.

These buzzwords currently circulating in the industry point to a new development in farming: using digital technology to collect, store and analyze data from producers’ fields in order to improve production on their farms.

The process isn’t entirely new. For some time, farmers have been using hardware and software systems for yield mapping, GPS guidance, variable-rate applications and other practices.

But while these tools collect large amounts of data, they don’t organize that data in one convenient place where farmers can visualize it and make decisions from it to benefit their farm operations.

Read Also

VIDEO: CornerStone planter pitches easy operation for farmers

Award-winning row unit by Precision Planting leans on its flexible design, ease of use and on-farm mainenance

Now a new digital tool from ag-tech companies does just that. It represents the latest wave in the ongoing digitization of agriculture. Some call it a revolution in farm technology.

“A lot of farmers have been collecting data over the years,” says Ron Makowsky, a digital integration specialist with Bayer Corporation which markets a digital platform called Climate FieldView.

“They’ve applied it through monitors across their farm operations. But in the past there hasn’t been a way to review that information easily throughout the course of the season because it’s been stuck in that monitor. What digital technology now is doing is taking that data — spraying herbicides, fertilizer placement — and viewing those different layers as producers watch their crops grow so they can see the effect of what they’ve done in those applications.”

In effect, says Makowsky, farmers are taking the data they already have and moving it up one step to watch their crops develop in real-time imagery throughout the growing season.

Tracking developing images (called data layers) can help farmers catch something happening — e.g. an insect outbreak or a disease issue — and act on them quickly, Makowsky says.

But the real benefit of the technology is that it enables farmers to spend less time sorting through data and more time making decisions to help them in the future, says Makowsky.

“Why I really like digital tools is that they help farmers visualize and compare at the end of the season to see for themselves through their harvest and yield information which is the better product so they can make better decisions moving forward for the next season and seasons beyond.”

Better insight

Another advantage is that the technology generates more information than one can get by scouting fields and collecting data based only on vision, says Easton Sellers, a farm management instructor with the University of Manitoba agriculture diploma program.

The tools provide a visual representation of variabilities within a field, as well as real-time field maps to show where input rates can be fine-tuned for maximum benefit, says Sellers.

“You can see on a screen where to put down inputs where they’re useful and not waste them on poorer areas,” he says.

Producers can also go back to maps collected in previous years to see how particular fields performed over time, Sellers adds.

But perhaps the biggest advantage is that the technology is not as daunting to use as one might think, Sellers says.

“So far it’s been a really positive experience for students,” says Sellers. “They don’t find it hard to learn how to use these things and they have access to support teams which help them stay comfortable with the hardware and software and troubleshoot things throughout the season.”

The U of M offered a course titled “Agricultural Technologies for Farm Management Decision Making” for the first time as a pilot project during 2021. Sellers, who has a U-pick fruit operation and orchard near Teulon, was part of the instructional team.

The course focused on data-based agronomic tools used on grain, oilseeds and specialty field crop operations. It hopes eventually to expand into the livestock sector, Sellers said.

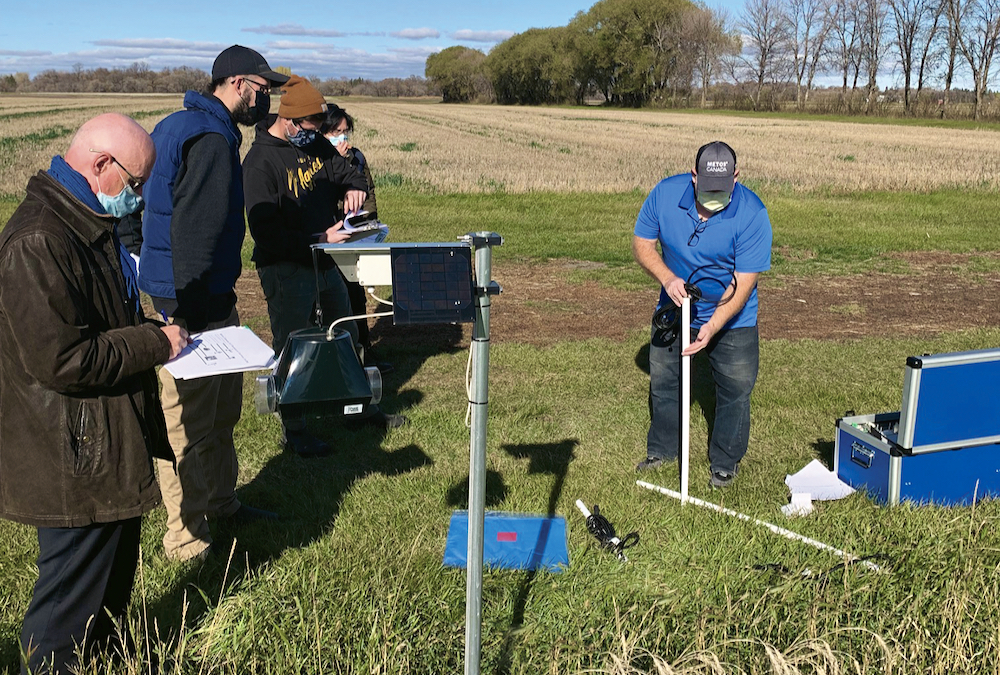

In offering the course, the U of M partnered with four ag-tech companies — Bayer, Farmers Edge, Enns Brothers and Metos Canada/Pessl Instruments — that supplied the technology for the course and gave a seminar for students in the field at the U of M’s Carman research farm.

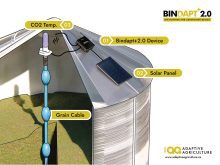

Sensory tools deployed for the project included a full weather station, deep-probe soil moisture stations (root zone soil moisture), surface soil monitoring stations for crop-specific models, the iScout insect monitoring tool, the CropView monitoring platform for crop development imagery and the LoRain platform that tracks rainfall, actual temperature and relative humidity enabling field-specific disease-risk modelling.

Guy Ash, global training head for Metos, said the course and instrumentation project was a good example of how the technology and its data-gathering abilities have been greatly simplified in recent years.

He describes the internet-enabled instruments as “transforming” how farmers manage their farm in every aspect, including fertility, seeding, spraying, disease management and harvest and storage.

The digital tools have become simpler to use and incorporate, and are a powerful form of risk management.

They give farm operators better information, in a more timely fashion, that lets them make better decisions, he said.

“These tools shave off traditional risks,” Ash said. “They provide exact information for production decisions.”

Farmer experience

Michael Reutter, who farms with his family near Grunthal, was one of eight students who took the course. He partnered with Bayer in using Climate FieldView for his project. Reutter says before taking the agricultural technology course, he had practically no experience with the program.

“Before taking the course, we were collecting all the data we collect today but we never gathered it consistently. So we had all the data but we never brought it all together to make any use of it,” says Reutter.

He says the family already had some of the hardware and software the course required. They bought some more FieldView drives and adaptive equipment and downloaded two program apps.

Reutter then set up FieldView in an air seeder, a corn planter, a sprayer and combines, and watched the data roll in.

“It was really helpful for our farm to have a visual of our field data. Saying the field averaged 76 bushels an acre of wheat is very nice but in variable soils some areas will yield around 100 bushels while other areas will be around 50. I think this will eventually give us an opportunity for variable rates,” Reutter says.

“It was also handy for running variety and fertilizer test trials. FieldView would keep track of all the different variables along with their locations in a field. It was just a lot less for us to worry about.”

The fact that field maps progress with the growing season is also very useful, Reutter continues. A new layer of data gets added for each activity. There’s a seeding layer at the start of the season, followed later by a sprayer layer, then a harvest layer at combining.

Reutter says it was also helpful to see on a map what fields were yielding in real time. This made it more comfortable to market some of the crops straight off the combine “because we felt we had a better idea of what the fields would actually yield based on what we were seeing and what we knew about the fields.” It also helped the family predict how much bin storage would be needed.

In addition, each year produces a new set of data, so a producer can compare maps to see how a field performed over time.

Reutter says elevation maps came in unexpectedly handy for a quarter section on which the family wanted to reroute the drainage. While the elevations were not in fine enough increments to show where ditches should go, they did reveal two feet of slope across the field, indicating where the water would want to flow.

Best of all, FieldView sharply reduces the need for paperwork. Reutter says the family used to record everything manually in a book: seeding dates, varieties used, spraying dates and rates, etc. FieldView does all that automatically, bringing everything together.

Lose the paper

The Reutters’ experience is a perfect example of why farmers should use digital technology, says Makowsky.

“They want a better system for record-keeping. They want to get away from pens, notebooks and binders of information. Having it in a digital solution means that it’s there. The information is all stored within a cloud. It’s always there and it’s accessible.”

Surveys show the average Canadian farmer is in his or her late 50s and getting older all the time. Some might wonder if this advanced level of digital technology might be too difficult for older farmers to handle. Reutter has a simple answer: Don’t worry. It’s user friendly. It’s easy to learn and use.

As an example, Reutter points to his Opa (grandfather) who is in his 70s, and used FieldView for the first time this year and aced it.

“He said, ‘This is almost too easy.’”

Nor is the technology prohibitively expensive. In the case of FieldView, Reutter says a farm needs only one annual subscription at a cost of $149. For each machine running FieldView, a drive costs $329 and an iPad mounting kit is $70. Add all three together and the total for one machine comes to $548 plus taxes.

At that rate, it doesn’t take long for the system to pay for itself, says Sellers.

“If you’re paying a couple hundred bucks for a piece of hardware and an annual subscription fee, that’s pennies compared to what you could do on a quarter section by reducing your input waste.”