The federal government’s goal to reduce emissions from nitrogen fertilizer is at odds with plans to increase agricultural exports by 55 per cent, say agriculture and fertilizer groups.

“This 55 [per cent] increase is attainable; however, it is unlikely to be achieved by the shackling of grain, pulse and oilseed farmers through the reduced use of fertilizer,” wrote the Western Canadian Wheat Growers (WCWG) in a submission to the government, released Aug. 31

The federal government recently finished consultations with agriculture and industry groups on how to reduce emissions from fertilizer by 30 per cent by 2030.

Read Also

Ship’s turning for gene-edited crops

More and more countries have decided that gene-edited crops will be treated the same as conventional plant breeding.

It also has a goal to increase agricultural exports to $85 billion in 2025 from $55 billion in 2015.

The groups said the federal government’s emissions goal cannot be achieved without reducing fertilizer use, and its export goals could not be achieved without increasing use.

- [READ MORE] Examining the burning nitrogen questions

- [READ MORE] Canada can cut fertilizer emissions 14 per cent by 2030, industry groups say

They also worried that, despite assurances to the contrary, the federal government will eventually regulate fertilizer use.

The concern is, “what if we’re unable to move the needle close enough to that 30 per cent in, say, five years?” said Branden Leslie, manager of policy and government relations with Grain Growers of Canada.

The Canola Council of Canada (CCC) has set a goal to produce 26 million tonnes of canola and 52 bushels per acre by 2025, an increase of 6.5 million tonnes over 2020 levels.

Better fertility management will get it part way there, to the tune of three bushels per acre more, said canola council president Jim Everson in an interview with the Co-operator.

Agronomic research is also part of the plan, but Everson said gains will be made through use of nitrogen, although not everywhere and not on all fields.

“Emissions can be reduced through ongoing advances in technology. However, a 30 [per cent] reduction by 2030 would require an absolute reduction in fertilizer use,” the WCWG said.

“The tonnage of emissions coming out of our fields and farms is a direct function of the tonnage of inputs we push in,” wrote the National Farmers Union in its own submission.

“A continued commitment to increasing yield and output by increasing the use of inputs is a de facto commitment to increasing emissions.”

Up and down?

That needn’t be true, at least in the short-term, said Mario Tenuta, the Senior Industrial Research Chair in 4R Nutrient Management at the University of Manitoba.

“Thirty per cent is actually a very conservative amount,” Tenuta told the Co-operator in an August interview.

He and his research colleagues have found multiple ways to reduce emissions from nitrogen fertilizer without cutting back on nutrients. These include nitrification inhibitors, polymer-coated urea, split application of nitrogen and growing legumes.

Further down the road, it becomes more complicated, Tenuta said in a Sept. 6 interview.

The 30 per cent goal is based on 2020 levels. Based on current trends, in 2030 yields will be higher, and so will crops’ nitrogen needs.

With a business-as-usual approach, “you would quickly find that you’d [need] more than 30 per cent reduction in 2030,” he said.

To maintain emission reduction gains 30 years into the future could be even more challenging.

“We’ll probably have to bank on new technologies,” Tenuta said. “To me, the real task is the future, is the 10 years plus down the road. What are we doing now to prepare ourselves down the road?”

Intensity, not absolutes

All groups asked the federal government to empower farmers to increase nutrient management through the 4R program. They asked for a combination of more financial support, research and technological support, agronomic and agrologic support, and to improve methodology used to measure emissions.

The current National Inventory Report doesn’t take management practices into account when calculating emissions from nitrogen fertilizer. Updates are in the works but will take years, Tenuta said.

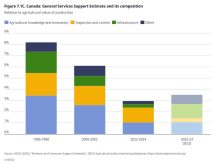

The GGC, WCWG, CCC and Fertilizer Canada asked the federal government to switch its goal from absolute emissions reduction to intensity reduction. In other words, lower emissions per bushel of crop produced.

“Focusing on absolute emissions from the sector will have severe consequences to the competitiveness of farmers and the fertilizer industry,” Fertilizer Canada wrote in its submission, released Sept. 7.

“Everyone wants to see emissions go down,” said Leslie. “We need to balance that short-term need for productivity increases against our need to lower emissions.”

An intensity goal would also be easier to hit, he added.

Fertilizer Canada said fertilizer emission intensity varies widely across Canada, with Saskatchewan, Manitoba and British Columbia among the lowest, and Quebec, Ontario and New Brunswick among the highest.

Applying 4R practices would therefore have a greater impact in higher-intensity regions of the country.

“A rational and achievable intensity-based target should be set that focuses on reducing the emissions it takes to produce a bushel of crop,” it said.

Fertilizer Canada did not say what that target should be. Leslie and Everson also declined to indicate an intensity reduction goal.

It should be noted that an intensity-based goal probably won’t reduce emissions in the long-term, said Tenuta and better technology will be needed to maintain reductions.

Not good enough?

While the NFU voiced support for 4R nutrient management, it said better management and technology would not be enough.

“Our efficiency levels and technological achievements are at historic highs, yet so too are the scale and menace of our problems,” the NFU wrote.

It argued that even if fertilizer is managed better, continuous increases in application in pursuit of higher yields will eventually undo progress.

“Transformative, foundational systemic change is needed,” the NFU wrote.

It said the federal government should broaden its focus from maximum output to maximizing farmers’ margins and incomes, as well as increasing the number of farmers.

“’Feeding the world’ is the last refuge of agribusiness profiteers and their confederates who want to maintain an atmosphere of food shortage, low supply and crisis in order to keep output and input-demand on ever-upward trajectories,” the NFU wrote. “Farmers need to step off the yield-and-output treadmill – the input-use treadmill.”

The NFU isn’t against increasing yields, said Darrin Qualman, NFU director of climate crisis policy and action. It’s against increasing yields by increasing harmful inputs.

Unintended consequences?

As many ag groups pointed out, yield reduction isn’t a good option. Neither is keeping production static, said Michael Von Massow, an associate professor in Food, Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of Guelph.

“Everything is connected to everything,” Von Massow said.

When Russia invaded Ukraine earlier this year, cutting off exports of grain and oilseed, customer countries suffered, Von Massow said, but prices rose everywhere.

Argentina set export controls on products like wheat to keep domestic prices down. Malaysia did the same for palm oil, he added.

“It’s sort of like dominos falling. You get one country starting to do it, then other countries start, and we exacerbate or worsen the issue around both pricing and availability of product.”

If Canada’s exports were static, world demand would continue to grow, Von Massow said. This would have a similar effect.

Reducing or capping exports might reduce emissions domestically, he added, but other countries might take up the slack.

“What happens if Brazil says, ‘well, we’re going to expand our production and continue to cut down a bunch of rainforests to expand our agricultural production?’”

Production shouldn’t be increased without a thought for emissions, Von Massow said. Serious conversations are needed about emissions, soil health and other sustainability issues.