It isn’t a setup you’d see any machinery company advise.

The black-and-white photo, circa 1943, shows Murray and Archie Dickson atop their family’s Nichols & Shepherd Red River Special.

The pull-type combine is hitched to a small, metal-wheeled tractor. There’s a long shaft with universal joints linking the tractor’s steering wheel to the one on the combine’s platform. A rope appears to work a lever mounted just behind the belt pulley, which probably works the clutch. Two ropes drop under the steering shaft, possibly to open and close the throttle and operate the kill switch.

Read Also

The sneak peek of Manitoba Ag Days 2026

Canada’s largest indoor farm show, Manitoba Ag Days, returns to Brandon’s Keystone Centre Jan. 20-22, 2026. Here’s what to expect this year.

The jury-rigged setup allowed both combine and tractor to be operated by one person and was the brainchild of the family’s patriarch, W.G. Dickson.

That one person would first start the tractor and combine engines, put the threshing body in motion, tie back one rope to engage the clutch, climb to the tractor and put it in gear, climb back to the combine and then let out the clutch rope. Only then could the outfit begin threshing.

Why it matters: Rural areas in Manitoba have spent decades trying to revitalize their communities, even as Manitoba’s population becomes more urban.

In a 2019 article, the Manitoba Agricultural Museum gave its best theory as to why the elder Dickson devised such a unit.

The Second World War was raging at the time the image was taken, and labour was short on the Prairies. The self-propelled combine was still in its infancy. Two of Dickson’s sons were in the air force. Archie appears in the photo because he was on leave at the time. The youngest was still in school.

Dickson had to find a way to bring in the crop alone.

In the two decades following the photo, mechanization would rapidly change the farming sector and, by extension, the Manitoban countryside.

The proportion of Manitobans living in rural areas began to decrease year over year starting after the Second World War.

Concern over the shrinking farm population eventually made its way to Manitoba’s legislature. The late-1960s and ‘70s government of Edward Schreyer became worried about the financial impacts to Manitoba’s highly agricultural economy. It led the government to implement the Stay Option, a policy of investment in agriculture and rural communities that purported to stem the tide of rural migration.

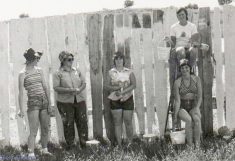

This included a youth summer work program in the mid-‘70s, dubbed the STEP program. It employed teams of rural high school students on local projects in their home communities under the supervision of post-secondary students. (For more on the STEP program, see the first story of our series, “How do you keep a kid on the farm?”)

Statistics over the following decades show little change in the rural population outflow.

As of the 2021 Census of Agriculture, the number of Manitoba farms had dropped just under 55 per cent compared to 1976, and rural Manitoba accounted for about a quarter of the province’s population.

Making it big

It is unlikely that today’s farmers would envy the way their parents or grandparents ran their operations.

Mechanization, along with the agrichemical advances and varietal development of the Green Revolution, saw production spike to unheard of levels as the 20th century wore on. Farmers today harvest more, harvest faster and use technological integration and know-how that previous generations would likely have described as science fiction.

Two years before W.G. Dickson rigged his combine to operate solo, there was one tractor for every 2.5 Prairie farms and one combine for every 11 farms. By 1976, there were about two tractors and “nearly one” combine per farm, author Gerald Friesen wrote in his book The Canadian Prairies: a History.

A farmer from 1940 wouldn’t understand the technology, crops or inputs that underpinned farming 40 years later, Friesen said. Increased mechanization and crop technology allowed individual farmers to handle larger acreages than ever before — and if they could, they did.

Farms began to consolidate. Between 1940 and 1980, the number of farms on the Prairies reduced by half. Land values rose dramatically.

Farm operating expenses, meanwhile, rose by a factor of five between 1956 and 1976. Farms were also making more money. Farm income tripled in the same window.

“Because the modern farm was likely to have been expanded recently, the interest payments on the price of the additional quarter-section would have to be met,” Friesen wrote.

Thus, he added, “the farmer of the 1980s worked with financial calculations on a daily basis where his predecessor would rarely have bothered, except in spring and fall.”

Farming became a large, capital-intensive business that “operated on a line of credit and relied on Mother Nature to produce satisfactory earnings,” Friesen said.

Farmers also became greater consumers, shopping in similar stores and sending kids to similar schools as the urban population. The farm was no longer a “self-sufficient garrison” from which “the family could surmount the vagaries of world prices changes and even of the weather.”

The modern farmer was tied into world markets, big business savvy and had big machinery to match. At the same time, those big machines and big farms needed fewer people to operate.

Fast travel

Other factors affecting rural Manitoba’s population drain may have had nothing to do with agricultural practice.

Gordon Goldsborough, a Manitoba author, historian and head researcher for the Manitoba Historical Society, noted the start of the depopulation slide dovetails with the period in which travel became easier.

“If I was pressed, I would say [rural depopulation began] sometime in the late 1940s, early 1950s, because that’s when the provincial government began putting resources into road construction in rural Manitoba,” he said.

Rural electrification also began near that time, he noted, and telephone service was advancing.

As the rural road system improved, residents had more freedom to move around and were no longer at the mercy of the train. They could drive to the nearest big town for groceries or haul grain to a more distant elevator for a better price.

In the 1960s, Goldsborough recalled, his grandparents would regularly drive from Ferndale, southwest of Winnipeg, to a downtown grocery store.

“That would have been unthinkable even probably a decade earlier, because the highway that they would have to take to get there wouldn’t have been passable for much of the year.”

In other words, rural people started leaving the countryside because they could, and the farm was just a telephone call or a drive away.

A tectonic shift

In 1941, 60 per cent of the Prairie population was rural. By 1981, only 30 per cent was rural and only 11 per cent lived on farms, wrote Friesen.

“In contrast to the golden days of rural life, the countryside was empty. And without people to participate and observe, the schools, churches, ball teams and sports days ceased to exist,” he said.

By the ‘70s, the archetype of the kid leaving the farm to make their way in the big city was well established.

Kim McConnell, who joined a STEP crew as a teenager, wanted to stay on the farm.

“That was my ultimate desire,” he said.

His parents had a rule: He could come home to farm, but he had to get an education first.

After university and a stint employed at a company selling crop inputs, he spent a year farming rented land. Then he lost that land base, and it didn’t feel right to “weasel in” on his mom and dad’s farm, he said.

McConnell returned to agribusiness, moved to Calgary, and got into marketing and communications. In 1984, he and his wife set up a marketing communications firm in their basement. Today, that firm is AdFarm, one of the largest agricultural marketing and communications firms in North America.

Close to home

Not all former rural STEP kids left their homes and farms. Robert Schwaluk, a team supervisor in 1973, still farms about a mile east of Shoal Lake, where he was born and raised.

Likewise, Margie Brincheski grew up in Point du Bois and boarded at Lac du Bonnet while she worked in the program. She had a summer romance with a local boy who eventually became her husband. They still farm together today.

– This series will continue in the Jan. 11 edition of the Manitoba Co-operator.