Although snow in the third week of April suggests otherwise, Manitoba is only weeks away from gardening season. And while the large farm garden is an institution in rural areas, the memory of soaring lettuce prices and food costs in general may have Manitobans everywhere looking for a little extra from their growing space.

Why it matters: Food inflation dropped from double-digit numbers seen in previous months, but grocery stores across Canada still charged 9.7 per cent more in March compared to March 2022.

Soil, water and sunlight are the foundation of any garden, and those starting a new garden area shouldn’t forget those fundamentals, said Getty Stewart, a home economist and author.

Read Also

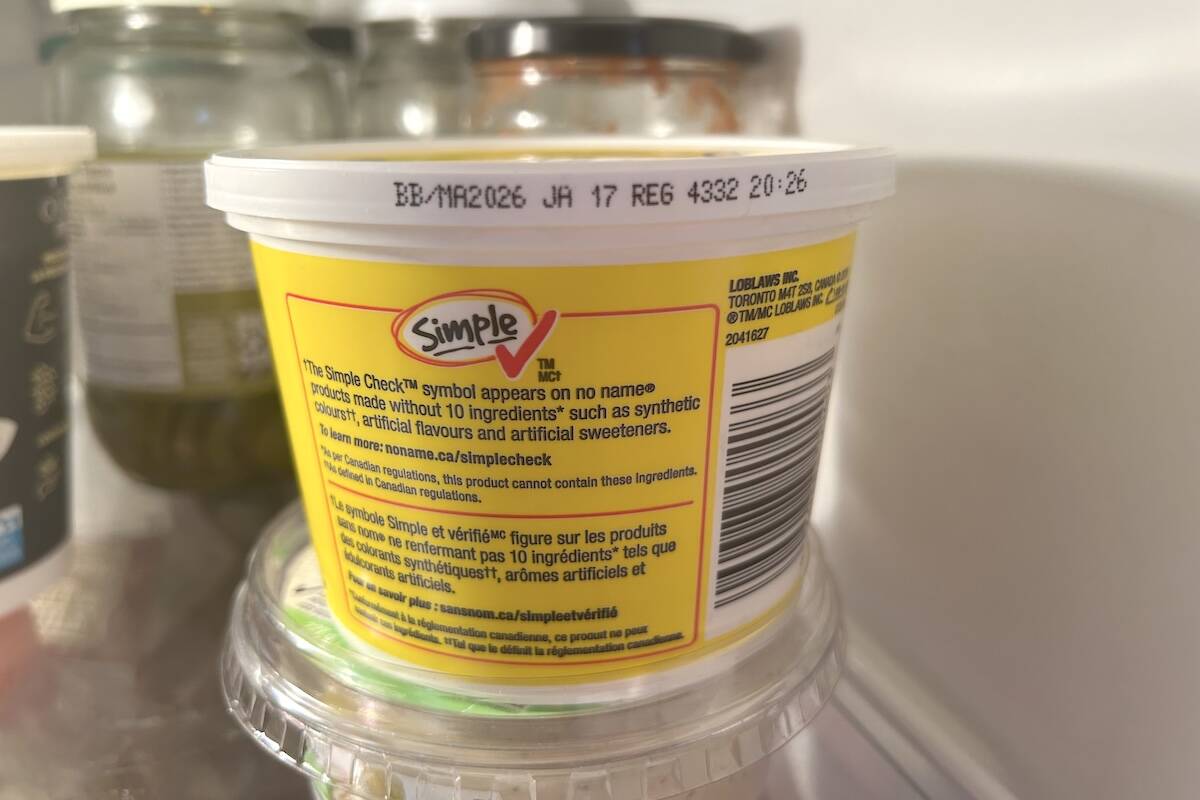

Best before doesn’t mean bad after

Best before dates are not expiry dates, and the confusion often leads to plenty of food waste.

“Just go for it,” she said. “But do remember that you’re working with Mother Nature. Know that you’ll have some ups and downs. Don’t take it personally, and don’t let it stop you from trying again because every year is different.”

Plan the water source and how it will get to the garden, she advised. A plot’s level of direct sunlight will be key for production.

Soil creates many of the same considerations as field crops grown at scale. Soil texture will help determine which crops will do well in the garden, and inform the gardener on how to plan their garden and prepare ground to optimize yields.

Root crops like carrots, for example, can have trouble pushing through stickier soils, Stewart said.

Best bang for buck

With the foundation laid, gardeners can turn to layout.

The square-foot method works well in raised beds and other small gardens, said Don Kinzler, a horticulture extension specialist at North Dakota State University.

It divides the garden into one-foot squares, then determines the optimal number of plants to occupy each square, Kinzler said. For instance, around 16 radishes can grow in a square foot, whereas a tomato plant would need four square feet.

If it’s an in-ground garden, he cautioned, gardeners must remember to add walkways to their plan. These should be mulched to conserve moisture and suppress weeds.

“The idea is to give each type of vegetable exactly the amount of space it needs to thrive, but no more and no less,” he said.

If plants are too close, they struggle to compete for resources. If they’re too far apart, they waste space. When spacing is right, plants shade the ground, reducing evaporation and weeds.

Guidelines for square-foot gardening can be found via Google search, Kinzler added.

Going vertical is another technique to conserve space. Beans, cucumbers and peas like to be off the ground, Stewart noted. It also makes them easier to pick and helps manage pests and disease.

Seeding times for crops like peas, spinach and lettuce can also be staggered to stretch harvest and availability of fresh produce, said Stewart.

In the same vein, crops like lettuce, radishes, peas and beets can be harvested and replanted for a second, later harvest, Kinzler added.

The right roster

Crop choice can maximize a garden’s output. For one thing, there’s variation in space.

“Pumpkins, they could take over your entire garden,” Kinzler noted, adding that space-hogs like squash, melons and cucumbers often have bush varieties that are more compact.

There is also the question of how much time a gardener can commit to maintenance and their level of expertise. The best plant choice for a veteran gardener who is retired, for example, may not match with a working-age newcomer.

Cabbage and cauliflower require close attention due to pests like flea beetles and cabbage moths, said Stewart.

“For a new gardener, I wouldn’t recommend that.”

Master gardener Jeannette Adams agreed, saying she avoids the brassica plant family, which includes cabbage, cauliflower and brussels sprouts, because of their vulnerability to pests.

There’s a similar difficulty spectrum when it comes to greens. Beginner or casual gardeners might gravitate toward salad greens like butterhead and leaf lettuce rather than the more difficult romaine or head lettuce, Adams said.

If space is at a premium, Stewart encouraged gardeners to choose crops where garden-fresh flavour makes a difference — tomatoes, for instance, or specialty varieties like delicata squash that are hard to find in the store. Corn, in contrast, requires a lot of space and can be readily bought in-season.

Adams reminded gardeners to buy good seed from reputable brands. Recognizable names from a garden centre give better odds than generic seeds bought from a dollar store.

“You don’t know how old those seeds are,” she said. “If you’re going to go to the expense and effort, then you want it to grow.”

She recommended tried and true varieties, likely labeled as bestsellers, customer favourites or award winners.

Finally, don’t go overboard. If you get a good crop of vegetables like cucumbers, Adams said, they’ll produce “like crazy.” Then you’ll either have to eat a lot, share, or find time to pickle or preserve them.

Minimizing waste

When it comes down to it, gardeners should grow what they want to eat, the three experts agreed.

“(There’s) no sense trying a bunch of new and trendy things and then you find out you don’t want them,” Adams said.

Stewart urged gardeners to think ahead about processing and storage. For instance, potatoes need cold storage, but not too cold, she said. The fridge is too cold. An insulated basement is probably too warm.

Processed potatoes don’t freeze well, she said. They’d need to be pressure canned due to their low acid content.

Expected maturity windows after seeding, plainly printed on seed packages, can also be a blueprint for strategic harvest and processing. For instance, if beans will be ready mid-July, you may not want to take two weeks of holiday at that time, or you could make arrangements for friends or family to take care of them.

If planning to make salsa, tomato sauce or other preserves, gardeners should follow proven recipes, Adams said. Marketing boards, home economists and canning equipment companies are all reliable sources.

“Grandma’s recipe may not work in today’s world,” she said.

Modern tomatoes may be lower in acid than the tomatoes of yesteryear. Recipes will compensate by adding acid, which is important for food safety when canning.

Finally, there’s always composting. Set up a system to convert plants and uneaten produce into useful compost and “at least it’s going back into the soil,” Adams said.

Fertilizer and soil health

NDSU recommends getting soil tested to set a fertility baseline.

“Adding fertilizer without knowing the soil test is kind of like adding salt to a soup without tasting it first,” Kinzler said. “There are real consequences for over-fertilizing.”

Too much nitrogen can result in an overabundance of leafy growth at the expense of fruit production. Too much phosphorus and potassium can burn plants.

If you can’t get a soil test, but want to add nutrients, organic fertilizers like manure and compost are safer bets, Kinzler said. They’re less concentrated and more gradual to take effect.

Organic and synthetic fertilizers have pros and cons, Kinzler added. Organics are slow acting but can last longer and add beneficial material to the soil. Synthetic fertilizers act faster but don’t last as long and don’t build the soil.

Adding compost or mulch can loosen and improve soils that are compacted or composed of heavy clay, Adams added. In her experience, adding these can reduce the need to till or turn the soil and is thus good for worms and microorganisms important to soil health.