It’s an icy, wind-whipped day. The brand new Parrish & Heimbecker (P&H) grain elevator outside Dugald towers above the snow-covered fields like its iconic ‘Prairie sentinel’ ancestors.

It’s big, modern, full service, and importantly — perfectly upright.

On the wall inside the main office hangs a photo of the elevator’s predecessor at Transcona, which operated successfully for over a century.

It was built in 1912 for the Canadian Pacific Railway. In 1913, operators filled the silos on only one side of the elevator. The full silos sank into the earth and the elevator tilted at an angle of nearly 29 degrees, the Manitoba Historical Society says.

By digging out the opposite side, CPR was able to right the elevator, albeit now sitting 20 feet lower than before, P&H construction engineer Zach Harrison told the Co-operator.

The incident is a well-known, geotechnical engineering case study, he added.

P&H bought the elevator in 1970, according to the Manitoba Historical Society, and operated until the new site was ready this summer.

Modern elevators are loaded corner to corner, and this one was given time to settle before ramping up to full swing.

“You’re safe. It won’t tip,” Harrison said.

The terminal includes a 25,000-tonne elevator, 150-car loop track on a Canadian National rail line, 6,000-tonne dry fertilizer shed, chemical shed, and seed treatment facility. The Co-operator toured the site on November 17.

“Because a good portion of our customer base is east of the city as well as northeast and southeast, we decided to make a commitment to the agricultural producers… and build a brand new terminal out here,” said general manager David Yarycky.

Safety — food safety, and for the people who work there — is a significant part of the elevator’s features.

As farmers will know well, the grain is probed before it actually reaches the elevator and samples are checked for out-of-condition grain, insects and contaminants.

“I’m sure if you poured yourself a bowl of cereal, you wouldn’t like to see a small pellet of fertilizer come out,” Yarycky said.

The system funnels the sample to the far end of the terminal’s office where staff can analyze it. The sampling system can call samples from either of the elevators’ two ‘legs’ (grain-elevating systems), the truck probe, and an unload pit.

The unload pit is used for dumping rail cars if a contaminant is found in them, and also if grain is brought by rail to be transported elsewhere. The site has done this with American corn this year.

Samples from each truck are kept for a year. Then, if a customer finds an issue with the grain, P&H can trace it back to the elevator, load and producer.

One thing about the new elevator, Yarycky said, it sure is clean. It has extensive dust control measures in place. For instance, the conveyor that brings the grain from the truck is enclosed along its length to keep dust from blowing everywhere.

Read Also

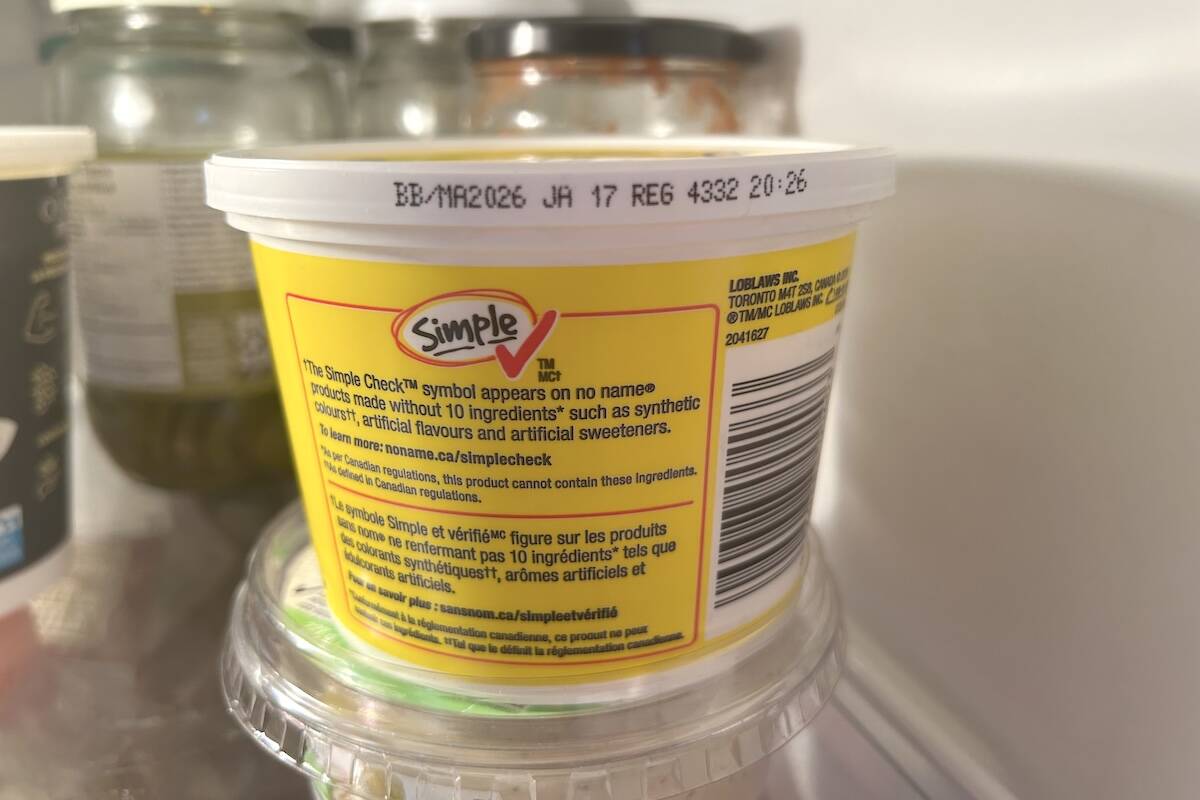

Best before doesn’t mean bad after

Best before dates are not expiry dates, and the confusion often leads to plenty of food waste.

There are also dust-collection systems along the conveyor.

“Dust can especially be a problem because: (a) for breathing in, and (b) some forms of grain dust, especially corn and oats, can be on the explosive side,” Yarycky said.

That’s no joke. In 2018, for instance, dust ignited at an elevator at Crystal City, Man. The explosion sent one employee to the hospital with second-degree burns. The fire levelled the elevator and spread to town businesses, destroying a hardware store, according to a 2018 CBC report.

At the P&H elevator, sensors throughout the conveyors and other machinery, monitor belts and bearings for any sign they’re heating up. They’ll automatically shut machinery down if they spot a problem.

Yarycky said he was particularly impressed with the ‘boot,’ or basement enclosing the bottom of the terminal’s bucket elevators.

“It’s massive,” he said, explaining that in old elevators the space can be so cramped it’s difficult to move, never mind deal with mechanical issues or spilled grain.

The space is large enough to not be considered a “confined space,” which would by law require many additional safety measures. In case of a medical emergency, a stretcher could be lowered in. An injured person wouldn’t need to be hauled out by rope.

“If you had to ask me what the best safety feature of the new elevators is, I would say this,” Yarycky said.

It’s also waterproofed.

Harrison and Yarycky explained that in older elevators, because the boot was so confined, workers were reluctant to go down to clean up spilled grain. The boot might fill with grain and muck, making it difficult to monitor the machinery inside.

“Grain would get over top of your bearings, and if you ever had a bearing heated up, then it would start a fire,” Yarycky said.

He’s sometimes flabbergasted how clean it is, he added.

Across the yard, the 6,000-tonne fertilizer shed holds all the essentials, along with options for micronutrient coatings.

Bulk fertilizer is dumped from a conveyor into its appropriate bin — wood lined, because fertilizer is incredibly corrosive and would eat through any mild steel. Harrison and Yarycky were keen to note the shed holds only non-combustible fertilizer. That too won’t blow up.

A front-end loader dumps fertilizer from the bins into hoppers, which each sit on load cells (scales, essentially) so when an employee punches in the required blend of nutrients, the system metes it out precisely.

Quickly too, Harrison assured the Co-operator. The system is capable of loading 300 tonnes per hour.

“Farmers are in and out… it’s very efficient,” he said.