It has happened only three times in the last seven or eight years of surveying canola fields for infections.

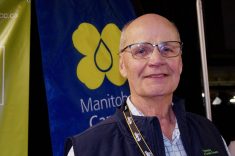

Manitoba Agriculture plant pathologist David Kaminski went into a field to gather data for the 2023 Canola Disease Survey and found clubroot.

“It’s kind of like looking for a needle in a haystack,” he said during a Crop Talk webinar hosted by the province Sept. 6. “It’s often just happenstance that we find a field with clubroot through our general survey. Most of the fields with symptomatic plants are only brought to our attention by agronomists or by growers themselves.”

Read Also

Can we trust the USDA crop data anymore?

Indications that farmers, analysts and traders have started to lose trust in data from the United States Department of Agriculture are hardly a surprise.

Why it matters: The annual survey indicates disease threats and tracks emerging problems like clubroot.

In this case, the clubroot finding wasn’t totally unexpected to the grower. A previous soil test had shown elevated spore counts.

The field was in the RM of Roblin, one of 11 municipalities where symptomatic fields (or fields with spore counts over 80,000 per gram of soil) had already been found, shown in last year’s provincial clubroot distribution map.

Of bigger note was severity of the infection. Among the plants plucked from the field, 20 per cent showed symptoms. Of those, most were “as bad as they can be,” Kaminski said.

The field rated a 2.5 severity rating out of three. A rating of one denotes “just the faintest evidence of symptoms, maybe on a secondary root,” Kaminski said.

Plants rating two to three face serious deformation and galling on the roots.

It’s an example of how tricky the disease can be to catch if growers aren’t looking for it. In this new case, the plants weren’t throwing many red flags above ground. The field was prematurely ripening and had stunted patches, but there was little serious sign of infection.

Move over, sclerotinia

The clubroot finding was one of several takeaways from the survey’s initial numbers.

Blackleg findings were no surprise. The pathogen is historically one of the most common in the province, and 2023 was no exception. This year, 86 per cent of surveyed fields had a blackleg infection and the number of infected plants averaged 11 per cent. Infections rated a 1.18 severity on a scale of five.

That’s in line with previous surveys, with Kaminski noting that “1.2 is pretty much the standard we’ve been seeing for five years now.”

Sclerotinia, typically also among the top two canola diseases, slid to almost insignificant levels. Only seven per cent of fields were found with the disease, with an incidence rate of less than half a per cent and severity of 0.16.

Manitobans can thank the dry year for that, said Kaminski. Last year, sclerotinia was found in 41 per cent of fields, at an incidence of three per cent and severity of 1.2.

This year, verticillium took the second-place slot. Infected plants were found in a quarter of surveyed fields, although incidence was low at 0.7 per cent.

No severity numbers were provided. Verticillium is a relative newcomer, Kaminski noted, and there isn’t a scale with which surveyors are confident.

Those numbers are down from last year, however. While verticillium did not overtake sclerotinia in 2022, it was found in 38 per cent of surveyed fields.

This year’s findings were unexpected, Kaminski said. Until now, verticillium has been on a steady rise.

The 2018 canola disease survey registered verticillium in less than 10 per cent of fields. By 2019, it had climbed to 18 per cent and during the next two years reached 30 per cent.

The disease earned a special mention from the Canola Council of Canada earlier this summer. The industry group put out a resource outlining identification tips.

Wrong kind of yellow

This year also saw a resurgence of aster yellows. Initial numbers showed 20 per cent of surveyed fields with symptoms. Last year, the disease registered in only four per cent of fields.

Since 2018, the highest infection rates topped out at 10 per cent, in 2021.

Field pathologists were forewarned that there might be a problem this year after seeing a significant number of aster leafhoppers, a vector for the disease.

Infected plants typically stand higher than the rest of the crop due to their limited seed set, according to the Canola Council of Canada. Producers will see malformed, bladder-ish leaf structures and greenish flowers.

Kaminski warned that, with the pink or purple discolouration on the edge of leaves also indicative of the disease, producers can easily mistake it for sulphur deficiency at the early stages.