Researchers are exploring whether resistance genes already present in cereals could help farmers manage bacterial leaf streak (BLS), a disease with limited control options and linked to major yield losses.

The trials at the Ian M. Morrison Research Station in Carman, Man., come at a critical time. BLS isn’t new to Canada, but infections are being reported with increasing regularity across the Prairies.

Read Also

Canada’s cereal breeding system is failing. Who fills the gap?

Agriculture Canada breeds 80 per cent of Canada’s wheat varieties. A new report says that system in no longer sustainable — and without a transition, some crops could quietly disappear from Prairie fields.

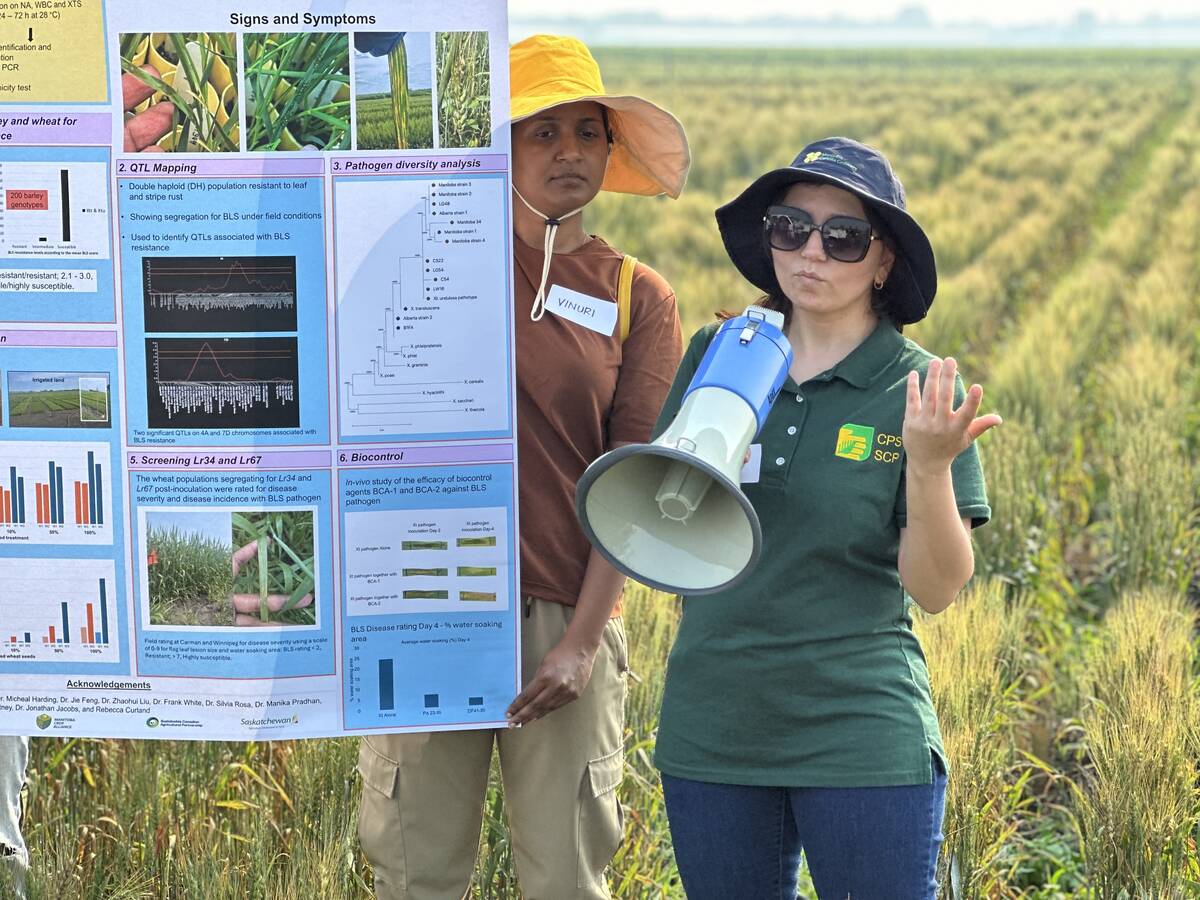

“Bacterial leaf streak has been detected in Canada since the 1920s but we are seeing the re-emergence of it. And it’s worsening rapidly,” said Shaheen Bibi, a plant pathologist and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Manitoba in Dilantha Fernando’s lab. Fernando and his BLS team lead the Carman trials.

WHY IT MATTERS: Bacterial leaf streak limits photosynthesis and, therefore, yield in cereal crops.

Fernando’s BLS team is running controlled trials with inoculated seed and irrigation to create conditions for infection. The aim is to better understand how much seed infestation translates into seedling infection, how moisture drives spread and whether genetic resistance is possible.

One project is characterizing Canadian isolates of the bacterium — collecting strains from different provinces to see how diverse they are and how that diversity affects disease severity. Another is mapping quantitative trait loci (QTLs), regions of DNA linked to traits such as disease resistance that breeders might eventually use. The team is also testing biocontrols that have shown promise in the greenhouse.

Most notably, they’re looking at cereal genes already known to confer disease resistance. The Manitoba team is focusing on two in particular — Lr34 and Lr67 — named for the leaf rust (Lr) resistance they provide. Both are broad-spectrum, meaning they protect against more than one disease. Lr67, for example, has shown some resistance to fusarium head blight and is most effective in mature plants.

Early trial results suggest Lr67 lines may show more resistance than Lr34. It’s too early to call, but the work could point to varieties with at least partial protection against bacterial leaf streak.

“What we want to see is whether there are any lines showing resistance to BLS that could be used in breeding programs in the future,” said Bibi.

Hard to identify

BLS often goes unreported because it mimics other cereal leaf diseases. Farmers may mistake it for tan spot or, in later stages, confuse necrotic lesions with natural senescence. Accurate diagnosis often requires lab expertise or a trained eye. That diagnostic challenge makes scouting all the more important during the growing season.

The disease is caused by Xanthomonas translucens, a bacterium with two pathovars of concern in Prairie cereals: pv. undulosa, which infects both wheat and barley, and pv. translucens, which primarily infects barley.

On leaves, the disease shows up as long, translucent streaks — hence the name translucens — that begin as small water-soaked lesions. Under wet conditions, lesions may exude a milky or yellow ooze — a key diagnostic feature that separates BLS from fungal leaf spots such as tan spot. As lesions mature, leaves lose photosynthetic area, and the flag leaf in particular, the part of the plant that contributes the most to grain fill, can be severely damaged.

The potential for loss is especially high because damage peaks at the flag-leaf stage. Severe infections destroy photosynthetic tissue, and anecdotal reports suggest yield reductions of up to 50 per cent.

But yield isn’t the only economic concern. The same bacterium can also infect heads, causing a symptom known as black chaff, which can reduce marketability by downgrading grain due to discoloration. Infected seed may also carry the pathogen, creating problems for seed use and resale.

Black chaff appears as dark streaks or bands across glumes and awns, sometimes alternating with healthy green tissue in awned varieties. In severe cases, glumes may turn completely black, and exudates can give heads a water-soaked appearance.

Conditions matter

BLS thrives during warm days, cool nights and in moist environments. Wetter years tend to bring more problems than drier ones, and areas that are naturally arid are less prone to outbreaks.

Moisture also drives how the disease moves within fields. Rain splash, wind-driven rain, irrigation and even mechanical activities can help spread bacteria from plant to plant. On the Prairies, irrigation is a particular concern.

The bacterium is primarily seed-borne but can also survive in crop residue, volunteers and perennial grasses. Because it is bacterial, standard fungicides, whether seed treatments or foliar sprays, are ineffective.

With no resistant varieties thus far in Canada, and no chemical options, growers are left with cultural practices and careful scouting to reduce risk. A group of Prairie cereal organizations, including SaskWheat, SaskBarley, Alberta Wheat, Alberta Barley and the Manitoba Crop Alliance, released a joint fact sheet in 2023 outlining key practices and scouting strategies to reduce inoculum levels and slow the spread of BLS.

Start with clean seed. Infected seed is the main source of inoculum. If BLS is suspected in a field, especially when black chaff is visible, harvested grain should not be used for seed. Certified seed is not routinely screened for Xanthomonas translucens in Canada, so growers are encouraged to ask about testing or send samples to independent labs.

Stretch the rotation. Extending the break between cereal crops to more than two years helps reduce inoculum in residue. Volunteers and grassy weeds should be controlled to cut down on secondary hosts.

Scout carefully. Begin at herbicide timing and continue through senescence, with extra passes after storms that might wound plants. The best time to distinguish BLS is at the flag-leaf stage, when translucent streaks are most visible. Avoid walking fields in wet conditions, since the disease can spread on boots and clothing.

Manage irrigation. In irrigated areas, water management can reduce risk. Practices such as irrigating in the evening when the canopy is already wet with dew, letting the canopy dry between sets, and avoiding unnecessary irrigation can shorten the hours of leaf wetness that favour bacterial spread.

Assume susceptibility. No Prairie varieties are currently rated for resistance to BLS. Some U.S. wheats (Glenn, Faller, Prosper, Bolles) and barleys (AAC Connect, AAC Synergy) have shown partial resistance, but local screening is still underway. For now, farmers should plan as though their chosen variety is susceptible.