Conditions weren’t ideal for verticillium stripe this year but the Canola Council of Canada says growers should stay alert when it comes to the disease.

“Verticillium stripe is a soil-borne pathogen and it overwinters in the soil,” said Courtney Boyachek, agronomy specialist and verticillium stripe lead with the council. “Last year was a bad year for infection, and the inoculum is still there. It’s something that we’re keeping in mind for this year, even though conditions are better.”

Why it matters: Harvest is the best time to scout for the disease, which hit problematic levels in parts of Saskatchewan and Manitoba in 2022.

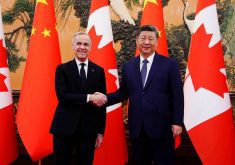

Read Also

Tie vote derails canola tariff compensation resolution at MCGA

Manitoba Canola Growers Association members were split on whether to push Ottawa for compensation for losses due to Chinese tariffs.

Verticillium stripe was first detected in Manitoba in 2014, the first North American case of the disease in an oilseed crop. Since then, it has been rising to yield-damaging levels in Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan and is now found in all growing regions across the Prairies.

“Over the last couple of years, infection levels have been high,” Boyachek said. “But last year was kind of the perfect storm for verticillium. So, it was pretty widespread across Manitoba and started to creep into Saskatchewan.”

READ MORE: Verticillium strip symptoms

Last year, cases were especially bad in the southwestern corner of Manitoba and southeastern Saskatchewan. Since the fungus is soil-borne, farmers in those areas started the year with potential for a severe outbreak.

Fortunately, 2023 weather may have mitigated the issue. Verticillium stripe flourishes in hot, wet conditions and infects plants during flowering.

“We did have adequate moisture in the spring, but we didn’t see any excess moisture,” Boyachek noted. “It did get hot, but it got hot before flowering. We saw a cooler flowering period…”

She says it’s too soon to know infection rates this year.

“We start to see it at 60 per cent seed colour change, so we’re still a little bit early to be noticing any symptoms.”

Harvest is the ideal time to scout for verticillium stripe because symptoms are most obvious.

The canola council’s messaging has ramped up in recent weeks so farmers will think about verticillium stripe as they prepare to take crop off the field. It has put out scouting tips and identification and symptom guides to help farmers distinguish it from blackleg and sclerotinia. Misdiagnosis is a common problem between the three diseases, and the same field can be infected by more than one of the three at a time.

Manitoba Canola Growers members who think they may have discovered verticillium stripe can get free testing through the Pest Surveillance Initiative, which uses DNA-based tools to single out the race or pathotype of detected diseases.

No answers

If testing does confirm the disease, there are no easy solutions. No fungicide or soil treatment has proven effective on verticillium stripe and no resistant variants have yet been developed.

“Once verticillium is there, there’s really nothing that you can do,” said Boyachek.

Accurate identification is all about managing infections in the future and avoiding spread.

That could require steps to keep the soil, and therefore the pathogen, in place. The canola council website recommends two- or three-year breaks between canola crops as good disease management in general, but warns that verticillium microsclerotia can remain viable for many years.

There is no good data that correlates infection rates with yield loss and profitability.

“We’re still not 100 per cent sure of the yield impacts of verticillium. We just don’t know those numbers quite yet,” said Boyachek.