New genomic research from Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (AAFC) could give agronomists a leg up in the fight against blackleg in canola.

Blackleg (Leptosphaeria maculans) is a severe fungal disease of canola plants, and with canola generating about one-quarter of all farm crop receipts in Canada, it is a serious threat to producers.

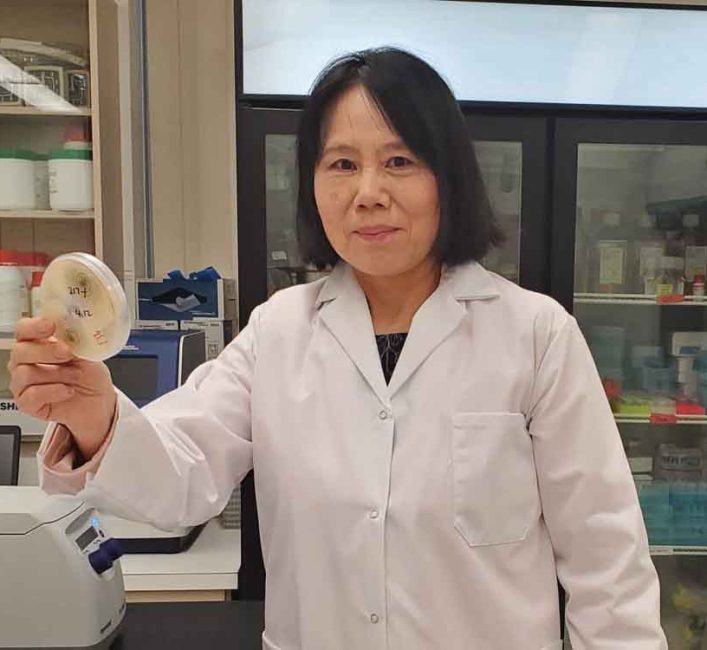

The new research was led by AAFC’s Dr. Fengqun Yu and her team of scientists at AAFC’s research and development centre in Saskatoon. The team recently completed the first large-scale resequencing of the blackleg pathogen.

Read Also

Can we trust the USDA crop data anymore?

Indications that farmers, analysts and traders have started to lose trust in data from the United States Department of Agriculture are hardly a surprise.

Blackleg was first discovered in northeast Saskatchewan in 1975. The first sequencing was done by French and Australian scientists more than a decade ago. But while those efforts created a useful reference genome, they focused only on islolates collected in France.

“Our work focuses on sequencing Canadian isolates,” says Yu. “We collected isolates from Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta over about two decades. We really wanted to look at the whole picture; at the genetic variation in the isolates across the Prairies.”

Canadian strains have been previously characterized by relatively few molecular markers, which has made it difficult to detect the variation responsible for the pathogen’s ability to adapt. But with the cost of DNA sequencing rapidly dropping, Yu’s team was able to select 162 strains taken from Western Canada. This allowed the team to get a clearer view of Canadian populations than ever before.

“It’s very exciting,” says Yu. “We found quite a few new variations and the isolates from Manitoba look highly diverse.”

The results showed the pathogen populations were composed of three distinct sub-groups — and that strains collected from 2012 to 2014 were more genetically diverse than those collected approximately five years earlier.

The sampled populations from Saskatchewan and Alberta were of similar genetic composition, while the Manitoba strains were highly diversified, which makes managing the disease more complicated. The difference in population structure among the provinces may be associated with precipitation, as fungal diseases like blackleg thrive in moist conditions.

Dane Froese, provincial oilseed specialist with Manitoba Agriculture, says he’s not surprised that genetic variation looks greater in Manitoba.

“We tend to have conditions that are more favourable for the disease,” he says. “Just based on our environmental patterns, we have a longer growing season, and we generally have more heat and more moisture – all things that favour disease development.”

That’s the kind of data that will lead to better management of the disease.

“This research is really exciting, because now we have the information we need to really understand the unique genetics and variations of blackleg-causing pathogen strains across Canada,” says Yu. “Armed with this knowledge, we can develop modern disease-resistant cultivars and discover new solutions to better help growers protect their crops from this serious disease.”

Froese agrees.

“For managing blackleg, it’s a positive step forward,” he says. “Understanding which gene populations are present and which ones are more dominant in different geographies in Manitoba makes breeding efforts more focused and more precise. A more precise tool is always what we need to manage a changing and ever-evolving disease.”

It’s also important research because blackleg is not easy to manage with fungicides, so developing resistant strains is an important way to combat the disease. Most strains available in Western Canada already have some level of blackleg resistance.

“Resistance is a combination of minor and major genes,” Froese says. “As pathogens shift, it becomes more and more critical for growers to be able to match their major resistance genes, in addition to their minor resistance genes, in their canola rotations.”

Yu says it is a constant battle between the pathogen and plant resistance, noting her research aims to be predictive and stay ahead of the disease. She says this new data is a major victory in the battle against blackleg.

“We are very excited to see it applied in the near future.”

However, farmers won’t see new resistant varieties for a while due to the way new discoveries wend their way through approval processes.

“My guess is the earliest some of these new findings will work their way into new crop breeding practices is five years down the road. It takes a year or two to make those crosses, to go through the co-op testing and then to hit registration,” he says. “But long term, it’s a positive story.”