After the worst year yet for the disease, verticillium stripe has moved from being a background concern to a standing agenda item at Prairie agronomy meetings.

AgDays in Brandon, Man., was no exception where the disease was the focus of a high-level panel discussion. However, it also surfaced repeatedly in technical sessions, hallway conversations and grower questions throughout the three-day show.

WHY IT MATTERS: With limited tools and slow progress on resistance, verticillium stripe is becoming a rising challenge for canola growers.

Read Also

Ship’s turning for gene-edited crops

More and more countries have decided that gene-edited crops will be treated the same as conventional plant breeding.

The disease was a key topic of Steven Smith’s presentation on the major issues facing western Manitoba farmers.

‘Verticillium Alley’

For Smith, an agronomist from Minnedosa, Man., verticillium stripe is anything but abstract. His region was one of the areas hardest hit by the disease last year, and he refers to a stretch of highway that cuts through his region as “Verticillium Alley.”

“In my area, I had fields where we had a 90 per cent infection rate on verticillium,” Smith said.

“Nine out of 10 stalks had severe symptoms. We had a corridor along Highway 16 from Minnedosa to Gladstone where it was sickening to drive. You could see it getting worse every day.”

Verticillium stripe is a soil-borne canola disease that causes stem striping, premature ripening and, in severe cases, lodging and yield loss. Although the pathogen has been present on the Prairies for more than a decade, the severity of the 2025 outbreak has pushed it into sharper focus.

The disease first took hold in Manitoba and remains most severe there, but provincial surveys now show it is established in Saskatchewan and continuing to move west.

Measuring yield impact

One of the biggest challenges for growers is understanding how verticillium stripe translates into yield loss.

Researchers speaking during a panel discussion at AgDays said the disease can cause severe damage at the individual plant level, but those effects do not always scale up neatly to the field level.

Stephen Fox, a plant breeder with DL Seeds, told the AgDays audience that the nature of the disease complicates efforts to measure yield loss. Traditional approaches, such as comparing sprayed and unsprayed fields, do not work for verticillium stripe.

“We don’t have any pesticides to do that job,” Fox said.

Complicating factors

His co-panellist, University of Manitoba plant pathologist Harmeet Singh Chawla, said environmental stress, uneven infection and interactions with other diseases all appear to influence how verticillium stripe expresses itself. As a result, symptom severity alone has proven to be an unreliable predictor of yield loss, adding to grower frustration.

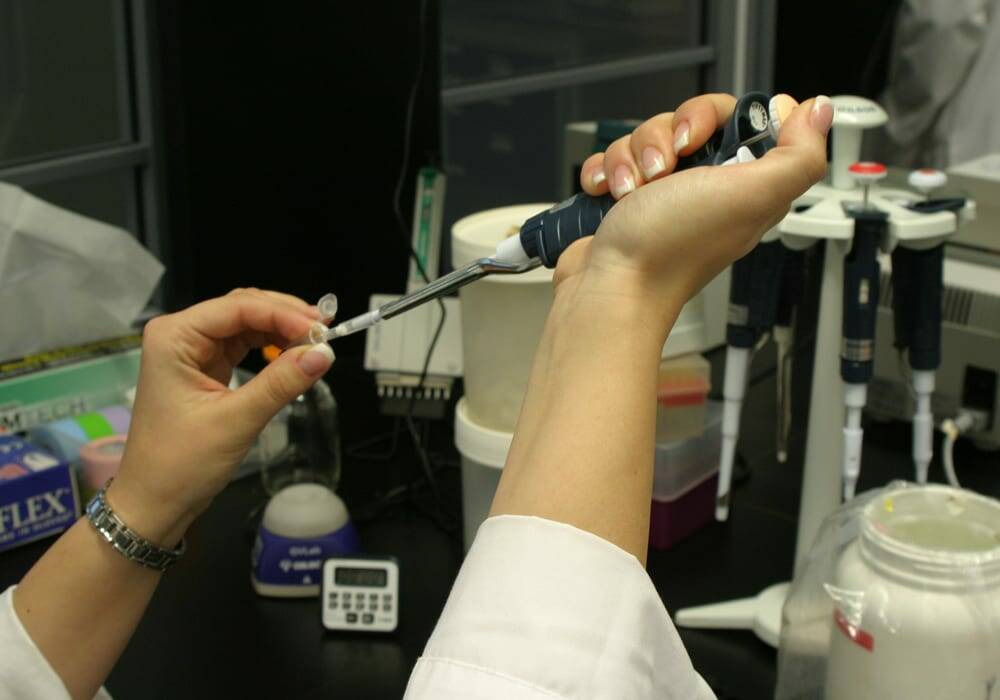

In addition to complicating yield data, emerging research hints that disease interactions could be even more concerning. University of Manitoba researchers have found evidence suggesting verticillium could be impacting blackleg resistance in canola.

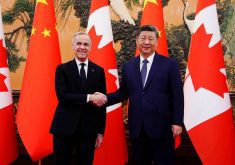

Chris Manchur, agronomy specialist with the Canola Council of Canada, addressed that question at St. Jean Farm Days in St. Jean Baptiste, Man., saying the interaction deserves close attention but cautioned that its full impact is not yet understood.

“It is too early to tell how significant of an impact this specific R-gene and verticillium interaction would have on yield in the field, but it underscores the importance of effective blackleg management to prevent any additive effects of both blackleg and verticillium stripe causing yield loss,” Manchur said.

Slow road to genetic resistance

Early efforts to improve verticillium tolerance were also discussed at the Manitoba Agronomists Conference in December, where researchers emphasized that progress is likely to come in small steps rather than through a single resistance breakthrough.

That theme resurfaced during the panel discussion at AgDays, where researchers cautioned against expecting quick solutions.

Unlike diseases such as blackleg, verticillium stripe does not appear to be controlled by single major resistance genes. Instead, resistance is believed to be quantitative, governed by many genes that each contribute small effects.

“Blackleg is usually controlled by a single gene, so if you have this gene present, then you get a complete resistance,” Chawla said in an interview following the AgDays panel.

“Whereas with verticillium, it’s controlled by multiple genes, and every gene has a small effect.”

That means resistance improvements are likely to be gradual and expressed as differences in performance under disease pressure, rather than clear-cut protection.

“So you’re not going to have a clear cut yes or no, but you’re going to have a resistance which will reduce the disease,” Chawla said.

Current management and caution

For now, management options remain limited.

There are no registered fungicides or seed treatments for verticillium stripe, and cultural practices such as swathing versus straight cutting have not consistently reduced soil inoculum.

Growers are being urged to view hybrid ratings as relative performance tools rather than resistance guarantees and to focus on managing other stresses that may amplify disease effects.

Smith cautioned growers to be suspicious of silver-bullet marketing claims.

While some varieties appear to perform better under pressure, the disease remains poorly understood and answers are unlikely to come quickly.

“We’re in infancy in verticillium,” he said.

“We don’t know, so watch the marketing.”