In the fall of 2014, Bruce Black of the Brandon area lent the museum copy negatives of photographs taken on the farms operated by the Black family in the Brandon area.

The museum was able to digitize the images taken from the negatives. Photos in this period are not common, as cameras and film were expensive. They were saved for special occasions as a result which resulted in the photos from this time period being largely of people and family events.

Photos of day-to-day agricultural activities are somewhat rare. The image above comes from this collection and shows the stacking of sheaves on one of the Black family farms sometime around the First World War.

Read Also

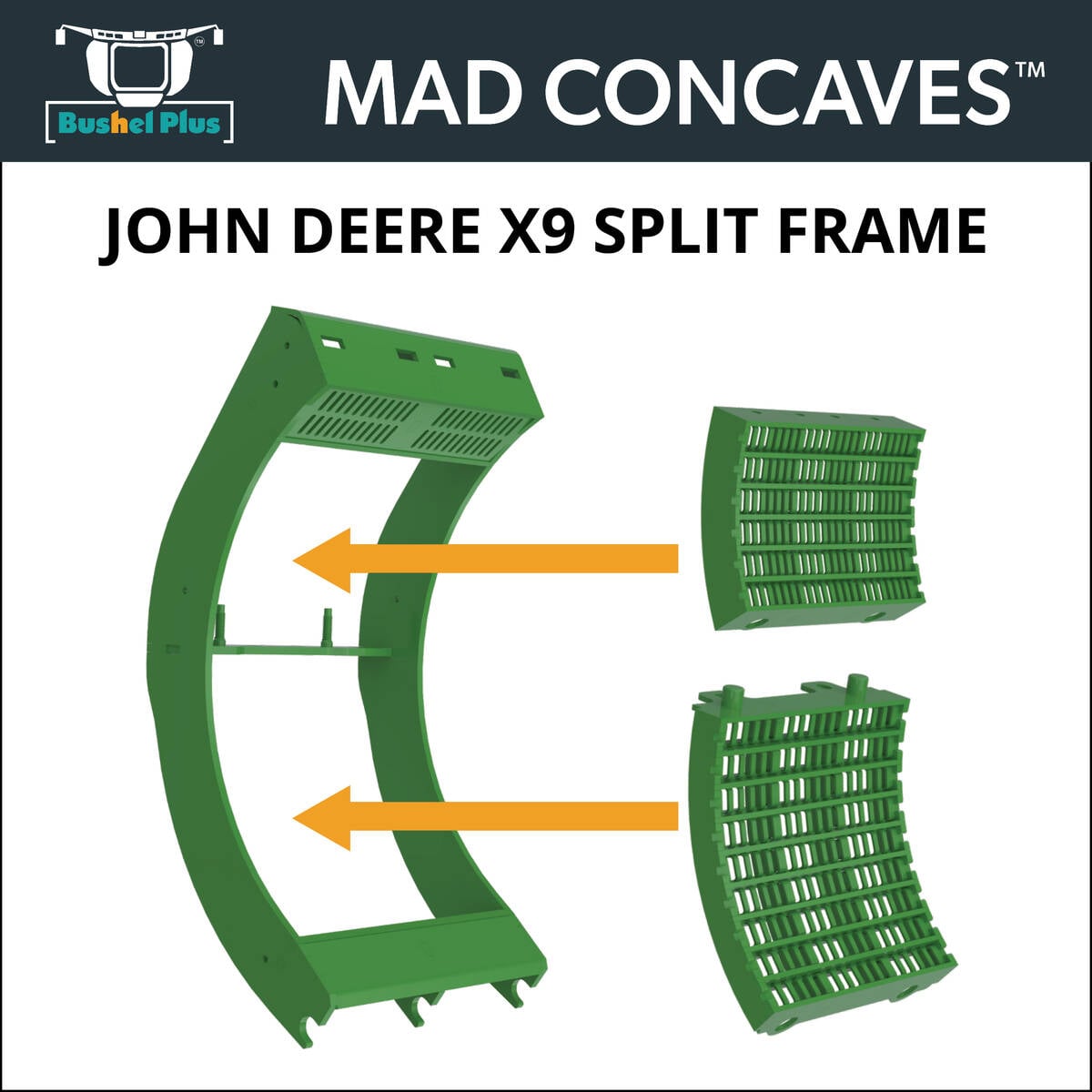

Bushel Plus launches Split-Frame MAD Concaves

New Bushel Plus Split-Frame MAD Concaves are designed for John Deere X9 combine owners looking for quick switches between crops.

Stacking sheaves was a somewhat common practice in the pioneer period for any number of reasons. The simplest reason would be that the farmer did not have enough on-farm bin space to hold grain and there was often limited possibilities to sell grain in the fall to an elevator for various reasons.

In the pioneer era, grain was exported off the Prairies through the Lakehead which closed when the Great Lakes froze over in the winter. So there was a great rush by farmers to sell grain in the fall before the Lakehead ceased operation for the winter.

In this era, obtaining loans from a bank was very difficult for a farmer and there were no government business risk programs. If the farmer could not sell grain or some other commodities, the farmer, more than likely, had no money to purchase winter supplies and pay bills. The result was there was a great rush by farmers to sell grain in the fall which then often resulted in the elevator system becoming plugged.

Rapid expansion

This was compounded by the rapid expansion of cultivated acres on the Prairies in the time period 1895 to 1914 which left the railways and grain-handling system struggling to provide rail cars, elevators and other needed facilities. If the farmer could not move grain to the elevator and farm bin space was limited, the best alternative was to stack the sheaves for the spring.

Another reason for stacking was that the farmer may have not had his own threshing machine and depended on a custom thresher. If the farmer was towards the end of the custom thresher’s run, the farmer may have felt it was wise to stack the sheaves to prevent weather damage and avoid the problems of an early snowfall as far as possible.

Oat sheaves may have been stacked as the farmer was using the oats for feed on the farm so there was no rush to thresh them and the farmer had other work that needed to be done before the snow flew, such as the fall plowing.

As can be seen here, the sheaves were stacked to form a beehive shape to shed rain as much as possible. The stacks here are estimated to be about 15 feet in diameter.

Of course the larger diameter the stack was, the greater the number of sheaves protected from the weather however, there was a limit to the diameter. If the diameter of the stack become too large it would be difficult, if not impossible, to fork the sheaves from the side of the stack farthest from the thresher into the thresher in one motion. The farmer would be aware of this and of how much labour he could find when time came to thresh the stacks. He would use the stack diameter that suited him.

Sloped to shed rain

The sheaves were laid with their heads facing inwards to further protect the grain. It is thought that a farmer building a stack worked from the inside to the outside and deliberately kept the inside of the stack somewhat higher so the sheaves sloped to the outside, again to better shed rain.

The stacks seen here are estimated at about 20 feet tall. Again, the taller the stack, the more grain could be protected from rain. However, there is a practical limit to how high the stacks were made, the physical ability of the sheaf pitcher on the wagon and how high this person could pitch sheaves.

On Sunday July 31, 2016 the Canadian Foodgrains Bank and the Manitoba Agricultural Museum will host Harvesting Hope: a World Record to Help the Hungry.

To help end global hunger, over 500 volunteers from 100 communities across Canada will operate 125 early 20th century threshing machines to harvest a 100-acre crop of wheat. When in operation, the equipment will require over four football fields of space. For more information on attending or how to participate please visit harvestinghope.ca or follow us on twitter @harvesthope2016.

The Manitoba Agricultural Museum is open year round and operates a website which can provide visitors with information on the museum including location and hours of operation.