I should know better, but I admit that I do it too.

I’ve just pulled some sliced chicken out of the fridge to make some sandwiches. I notice the chicken is within its use-by date, but I’m still suspicious. Another member of the family has unlovingly ripped open the packaging and the slices have been sitting exposed in the fridge for several days.

Wondering if the chicken is still usable, I give it a good sniff, hoping for some evidence that it is still good or has gone off.

Read Also

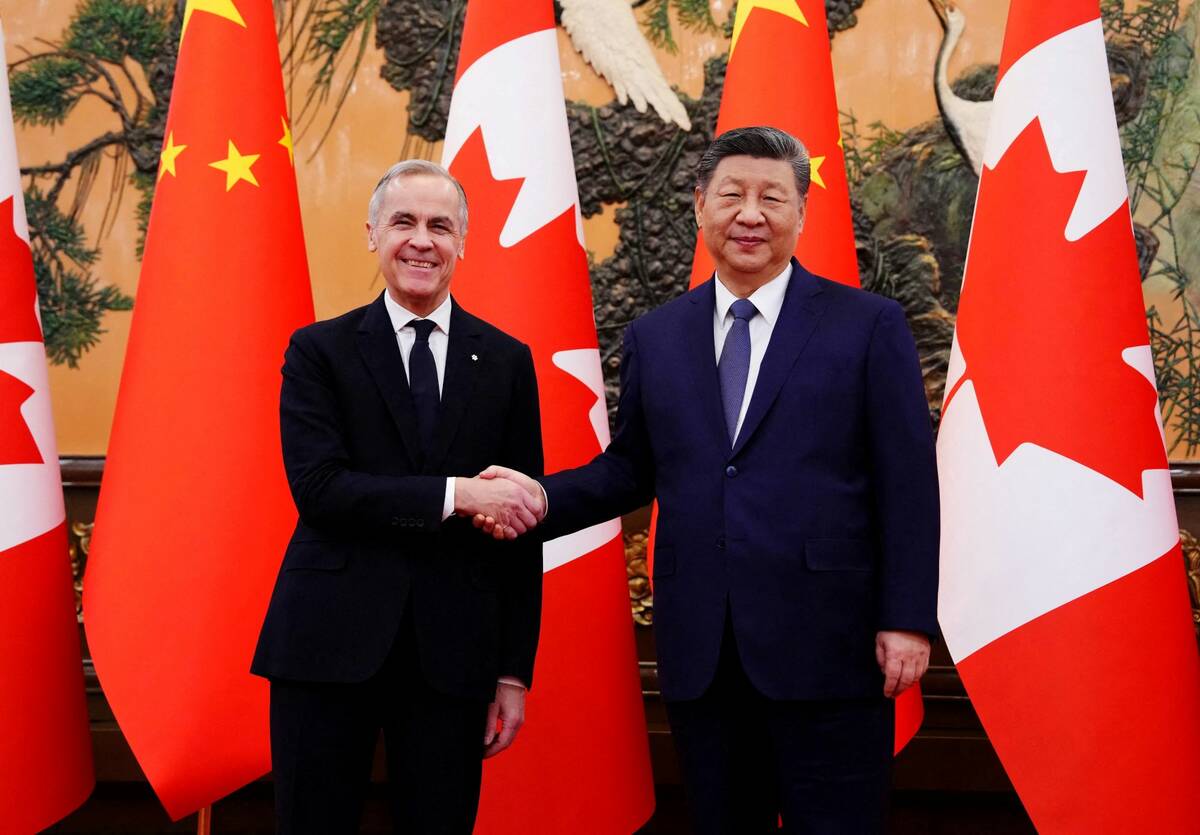

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China is a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

I should know better because I’m a microbiologist and I know the microbes that I might be worried about making me sick have no smell. Yet, there I am, trying and failing to give myself confidence with the old sniff test.

It’s certainly true that some microbes create odours when they are growing. Favourites include the lovely smell of yeast in freshly risen or baked bread, which is in stark contrast to – and please excuse the toilet humour – the aversion we all have to the gaseous concoctions created by our own bodies’ microbes that come in the form of flatulence or bad breath.

These gases arise when microbial populations are growing and becoming abundant – when the metabolism of each microbial resident converts carbon and other elements into sources of energy or building blocks for their own cellular structure.

However, the microbes most commonly associated with foodborne illness, such as listeria and salmonella, are nearly impossible to pick up with the sniff test.

Even if present – and the risk is thankfully relatively low – these bacteria would probably be at such a small amount in the food that any metabolic action (and then odour production) would be entirely imperceptible to our noses.

Also, any “eau de listeria” would be indistinguishable from the minor odours made by more abundant microbial species that are common and expected to be on our foods, and which cause us no health concerns.

Yes, there’s a very small chance that listeria may be present in the smoked salmon that I picked up at the coastal smokehouse last week. But absolutely no chance that my olfactory senses can detect any hints of listeria over the delicious smells of the dill and salts and smoke that make up the product.

Back to my sandwich construction. There’s even less of a chance of smelling any salmonella on the tomato that I dug from the fruit and veggie drawer in the fridge, even if I had super salmonella-smelling powers, which I don’t.

If this pathogen was on the tomato, it was probably introduced by contaminated water on the farm while the tomato was growing, so it is not on the surface, but within the tomato and doubly impossible to smell.

It is possible to detect when food is spoiled – another action of microbes, as they eat away at food that has been left too long or in the wrong storage conditions.

This is one reason why a more appropriate use of the sniff test is to suss out spoiled milk and help limit food waste, rather than throw out milk that might otherwise be safe. And for some foods – think of the microbial contribution to the finest cheeses – it is a culinary attribute to be malodorous.

While my wife disagrees with the aromatic attributes of some fermented foods (such as kimchi) and has banned them from the house, these are definitely not spoiled and should not be destined for the bin.

For other foods, such as fresh fruits or vegetables or milk, I still pay heed to any odours suggestive of spoilage and take these as a warning to do a better job of storing that particular food type in the future, or to make less or buy less if I’m not eating it in time.

I also reflect that some causes of foodborne illness are still unknown to us. While many cases of illness are caused by bacterial contaminants such as campylobacter or the other microbes I’ve mentioned, there are just as many cases where we don’t yet know the source.

But we’re getting better at this too, as scientists create tools much more accurate than our nose at detecting foodborne pathogens.

So, if I’m ever worried about becoming sick from my food, my energies are best spent on storing them at the right temperature and cooking them for the right amount of time rather than trusting my nose to sniff out a pathogen.

I wouldn’t even trust my nose to tell the difference between a cabernet and shiraz, let alone campylobacter and salmonella.

– Matthew Gilmour is a Group Leader in the ‘Microbes in the Food Chain’ programme at the Quadram Institute Bioscience. This article first appeared in the Conversation, by Reuters.