There once was a rooster on our farm that was so nasty and unpredictable, he wound up in the stewing pot after a violent confrontation with Uncle Jerry — an event that even decades after the fact remains a cherished bit of family folklore.

That rooster was big, beautiful and fearless. He ruled the roost with ferocious authority until his untimely demise, after which everyone breathed a little easier when moving about the yard. But he came by his aggression honestly. It was in his genes, traits which may have contributed as much to his survival in the wild as they did to his downfall in domesticity.

Read Also

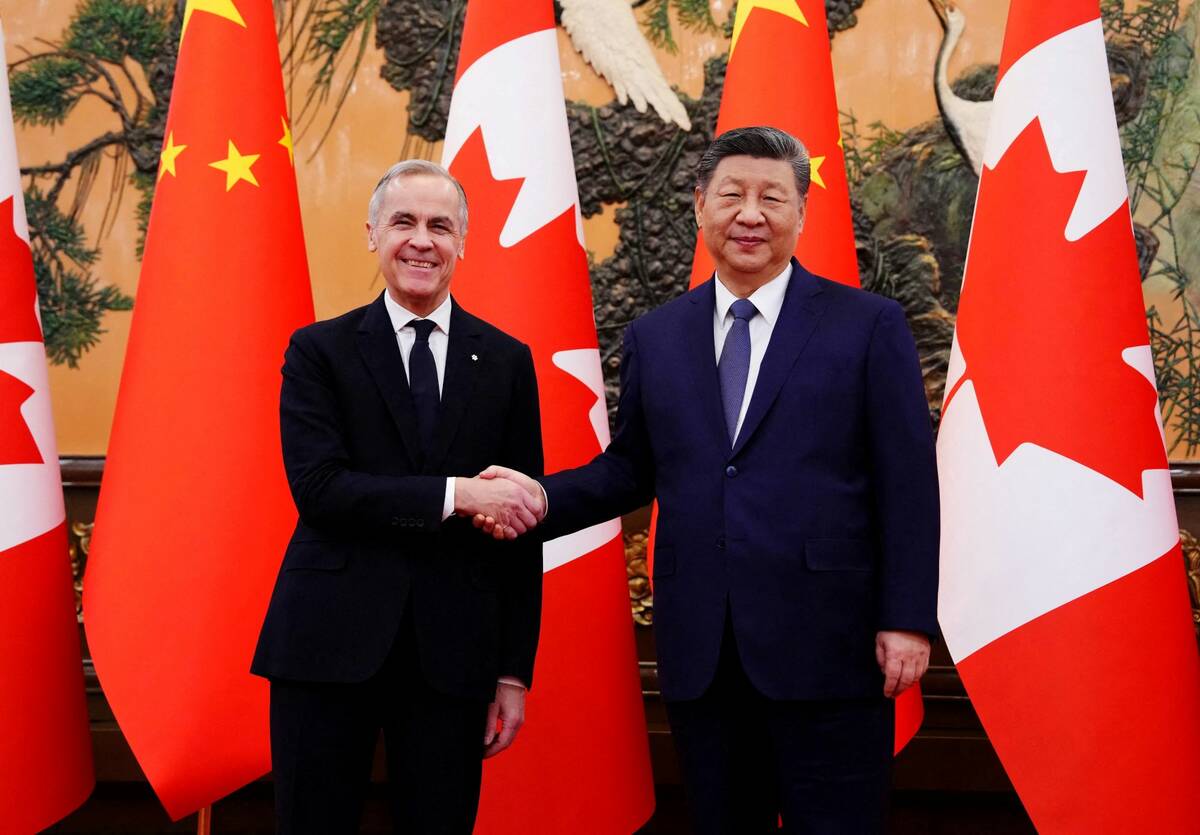

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China is a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

How genetics are selected and the traits that emerge in commercial production are among the issues dealt with in newly released research reports prepared for the National Farm Animal Care Council committees updating the codes for the care and handling of poultry raised for meat and egg production in Canada. These reports address some of the welfare issues created as a result of commercial breeding choices.

One of the topics dealt with in the scientific review is aggressive, sometimes murderous, mating behaviour exhibited by male broiler breeders. Apparently, due to a combination of genetics and how they are raised, male broiler breeders have a harder time attracting the girls than their counterparts in the wild.

In layperson’s terms, it’s because they skip the dating and go straight to mating. “Males appear to be motivated to copulate, but are not communicating this with the females, either through their inability or lack of motivation to perform courtship behaviour. Certain courtship behaviours such as waltzing, tidbitting and high-step advances appear at low frequencies or not at all in commercial broiler breeders.”

The females aren’t just playing hard to get, they’re running for their lives.

While it’s not conclusive, one theory is that raising males and females together can help stimulate some of the courtship behaviours that get both parties in the mood.

- From the Alberta Farmer Express: Manitoba hens to live in enriched housing

Scientists have also looked at the aggressiveness inherent in different strains of breeding stock, as well as the fact that these birds have been bred for meat yield. Their breast bones are now so big it’s difficult for them to mate, which is understandably frustrating.

Another issue related to meat yield genetics and aggression is the fact that these birds tend to be hungry — all the time. The breeders have become highly efficient at making birds grow, but nothing has changed about their appetites. So their feed intake is restricted to prevent them from collapsing under their own weight.

Feeding them every day instead of every second day was shown to reduce the amount of overall aggression such as pecking, but had no effect on the bad breeding behaviour.

It’s unclear how these reports will support the work of NFACC as committees update the codes for care and handling for poultry raised for egg and meat production in Canada. That process is still to be completed.

But these scientific reviews offer a glimpse into the imbalances that can result from our genetic selection of animals and plants according to a single-minded focus on production efficiency.

Examples abound of some of the welfare trade-offs, of which society increasingly takes a dim view. A federal scientist speaking to the recent Livestock Genomics in Alberta conference said breeding for traits that improve livestock health and performance have fallen by the wayside.

As reported in Alberta Farmer, Karen Schwartzkopf-Genswein pointed out that although production levels of meat and milk have more than doubled in North America since the 1960s, there have been unintended consequences.

For example, high-producing dairy cows are more prone to mastitis, lower fertility levels and higher rates of lameness. Laying hens bred to pour all their resources into egg production suffer from foot problems and brittle bones due to calcium deficiencies.

Researchers’ ability to select for specific traits is improving all the time and Schwartzkopf-Genswein suggests the advent of molecular breeding provides an opportunity to achieve better welfare outcomes.

The same goes for how livestock is managed. The pressure continues to grow on industry to provide so-called “enrichment” or housing and management practices that allow animals to exhibit natural behaviours.

Beef cattle producers are among the few who still make their own genetic selections to build herds that respond to their individual environment and management. They know all too well that genetics that produce big calves are only an asset if their cows can deliver them without a vet’s assistance.

Instead of a trade-off between traits that enhance productivity and animal welfare, the goal should be balance.