Death, taxes, and a post-harvest rally in wheat prices — all things farmers can count on.

Chuck Penner, of Left Field Commodity Research, told a recent Manitoba Crop Alliance webinar that seasonal price patterns are so predictable they’re vastly more important than trying to predict capricious markets and what direction they might head.

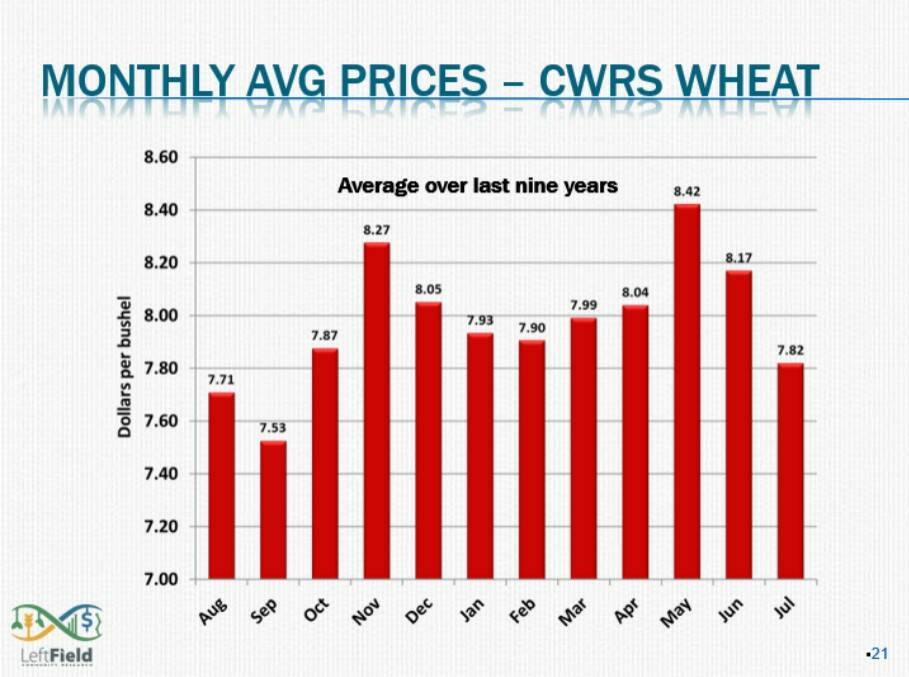

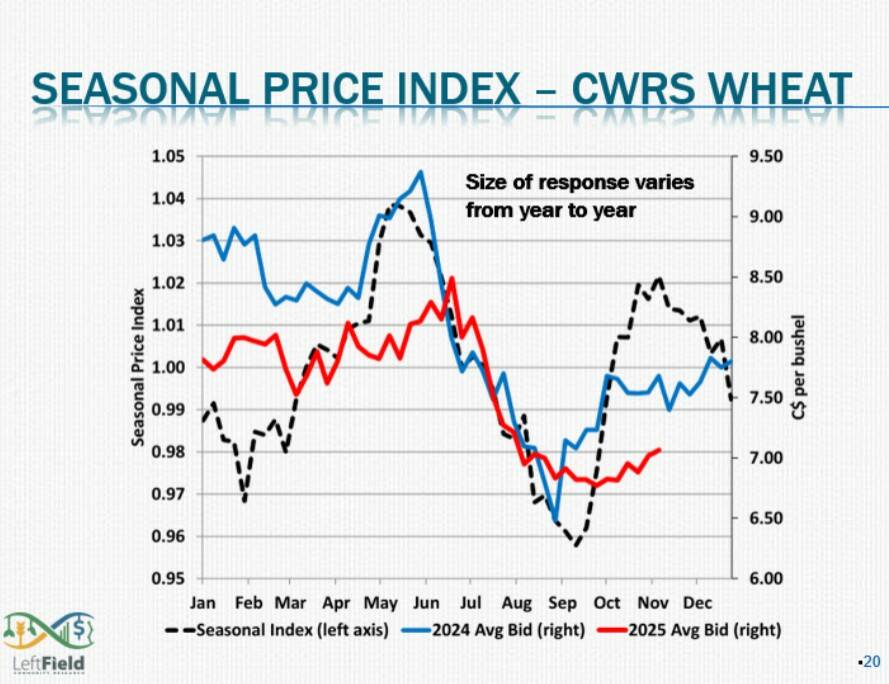

For example, that post-harvest rally in wheat prices has panned out for every one of the past nine years, and prices gained an average of 83 cents per bushel by late October.

Read Also

Farm Credit Canada forecasts higher farm costs for 2026

Canadian farmers should brace for higher costs in 2026, Farm Credit Canada warns, although there’s some bright financial news for cattle

WHY IT MATTERS: Farmers who use seasonal patterns to guide sales decisions can manage risk more effectively and capture stronger prices without betting on unpredictable markets.

After nearly 30 years in the grain industry, Penner believes that forecasting future prices is largely guesswork. Instead, he’s focused on consistent patterns in when prices tend to be stronger or weaker throughout the year.

Using red spring wheat as a case study, Penner showed that prices hit their lowest points at harvest, but the post-harvest recovery has been remarkably consistent.

His analysis demonstrated that by the end of October, wheat prices were higher than the September low in all nine years he studied, gaining that average of 83 cents/bu., or 11 per cent.

The gains are larger for farmers who can wait until the primary seasonal high in mid-May. Over the same nine-year period, prices averaged $1.31/bu. higher than harvest lows, with gains occurring every single year.

This pattern exists because of consistent behaviour by buyers and sellers. Harvest pressure depresses prices. Post-harvest rallies happen as grain moves into consumption channels. Spring highs often develop as buyers secure supplies before new crop uncertainty sets in.

Know your costs first

Price isn’t the most important factor in the sales calculation, though. That’s reserved for what it costs a grower to produce a bushel or tonne.

Penner stressed that before farmers can evaluate whether a price is worth taking, they need to know what it costs to grow their crop.

He recommended calculating production costs per bushel or tonne, knowing break-even prices, and understanding cash flow obligations over the coming year, including loan payments, input prices, and living expenses.

Just because a farmer needs a certain price, doesn’t mean the market will provide it, as Alberta Agriculture’s marketing guide notes. The guide’s analysis of 2013-2022 canola prices found that prices reached at least $425/tonne 84 per cent of the time, but hit $950/tonne or higher only six per cent of the time. Farmers waiting for that top six per cent need a backup plan.

Futures and basis

Every cash price quote has two components: the futures price and the basis. Those two components, in concert, are trying to tell you something.

The futures price reflects board supply and demand fundamentals, such as global production, consumption, and stocks.

The basis is the difference between the local cash price and that futures prices. A strong basis signals tight local supplies or robust demand, while a weak basis suggests local oversupply or sluggish demand.

When future prices are strong but local basis is weak, which is common at harvest, it’s a signal to either store grain and wait for basis to improve or consider hedging to lock in the good futures price while maintaining flexibility on when and where to deliver, Penner said.

Hedging means selling futures contracts while holding physical grain. If prices fall, losses on the physical grain are offset by gains on the futures position. If prices rise, the futures position loses money, but the grain is worth more. Either way, the price level is locked in.

The Alberta guide says that farmers are exposed to basis changes when hedging, but basis risk is usually much smaller than overall price risk.

Different scenarios, different tools

Alberta Agriculture recommends different marketing approaches depending on prevailing market conditions.

When both futures and basis are strong, the guide suggests pricing cash grain or signing a deferred delivery contract to lock in both components.

When both are weak, which is common in the post-harvest period, the guide advises to store if possible and wait for one or both components to improve. This is where Penner said his seasonal data becomes most relevant.

When futures are weak but basis is surprisingly strong, Alberta Agriculture recommends farmers sell at current cash prices to capture the strong basis, then buy futures or call options if they expect futures prices to rally. Alternatively, farmers can sign a basis contract, locking in just the strong local basis while leaving the futures price open.

The freight component

Penner’s research uncovered another pattern many farmers may not have noticed: rail freight costs themselves are seasonal.

Analyzing data from the Quorum Corporation, he found freight rates from Manitoba to Thunder Bay and those from Saskatchewan to Vancouver consistently rise in fall, then decline in spring, likely related to how freight caps are calculated. The swing runs $12 to $20/tonne, depending on the corridor, Penner said.

“Just waiting until the spring can help you, just from a freight perspective, in terms of your basis.”

Harvest pressure sales

Penner is skeptical of the pressure tactics farmers often hear at harvest.

“Every summer, there’s this doom and gloom. Prices are declining and people get really weighed down, and all of the news becomes negative. But that’s what happens to prices every single summer,” he said.

He’s particularly wary of buyer warnings that tell farmers, “well, you better get your wheat price now, because we may not be moving it, you may not be able to move it by December,” Penner added.

His nine years of wheat data suggests those warnings rarely play out as predicted, but he added that farmers still need to evaluate their individual situations, including storage capacity, cash flow obligations, and whether there are signals that this year is different.

When patterns break down

Major trade disruption can override seasonal patterns entirely, Penner said. He pointed to 2017-18, when India imposed tariffs on pea imports.

“It was at the harvest lows, and then it got even lower,” he said.

This year’s dual tariffs on peas from both India and China present similar challenges.

In these situations, farmers need to recognize the pattern isn’t working and adjust, Penner said.

“If it’s having a hard time recovering from those harvest lows, there’s a signal that I need to maybe be a little more defensive in my sales strategy.”

In this case, Penner suggests falling back on other approaches, including evaluating whether current prices are above break even and taking some profits, or being more responsive to premium opportunities from buyers if the timing isn’t seasonally ideal.

Forward contracting timing

Penner’s analysis of six years of forward contract bids revealed that January is usually the weakest time to lock in new crop prices, while May and June are usually strongest.

“Being patient in terms of forward contracting can also be very profitable,” he said, but he added that it works most years, but not all years. In years when prices are trending lower, early forward contracts might be the better choice.

Farmers should also consider what basis is being offered for their expected delivery period. A strong basis offer for future delivery might be worth locking in through a deferred delivery contract, even if futures prices are expected to improve, he added.

Alberta Agriculture’s guide says that farmers can sometimes lock in basis through a basis contract while leaving futures price open, giving flexibility to price the futures component later.

Costs of waiting

Penner’s analysis, however, doesn’t account for the cost of patience, he said.

Farmers storing grain while waiting for better prices pay interest on operating loans, storage costs, and potentially face quality risks. Farmers need to calculate whether seasonal price improvements actually exceed carrying costs, he said.

Penner also believes that risk tolerance varies. Some farmers are comfortable holding grain for months, while others prefer the certainty of cash in hand, even at a lower price.

One tool

Penner positioned his seasonal analysis as one input into marketing decisions, not a complete strategy.

“Shade your strategy toward those odds. Don’t bet everything on it,” he said. “And these price highs or lows can be extended.”

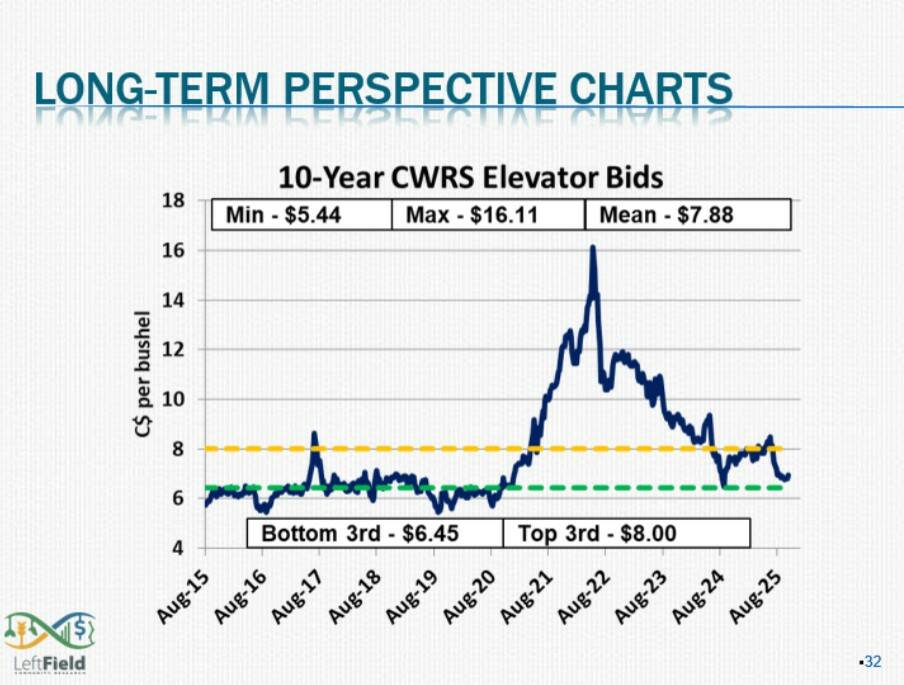

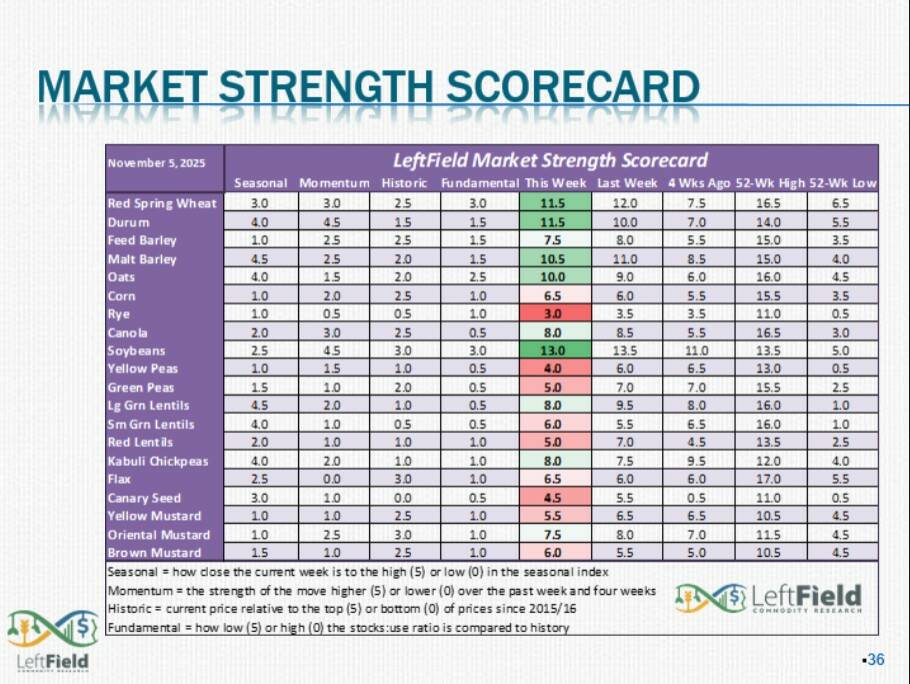

Penner encourages farmers to maintain perspective using historical price ranges, evaluating whether today’s price falls in the top third, middle third, or bottom third of the 10-year range.

“If we’re at the lows, that means there’s more likely a chance of prices moving higher. There’s more upside reward than there is more risk of downside,” Penner said.

Marketing framework

Alberta Agriculture recommends a structured approach to marketing planning. The guide says farmers must decide what to produce using price signals, market outlook, and agronomic needs.

Then, they should calculate production costs per bushel or tonne to identify which enterprises are most profitable. After that, price targets can be set by determining break even prices, understanding cash flow needs, and setting realistic targets based on market potential.

Sale timing should be planned using tools like seasonal analysis alongside cash flow needs and storage capacity, the guide says. Then, it’s important to stay informed by monitoring basis levels, future prices, and market fundamentals.

Next, it’s important to understand the mechanics and appropriate use of different marketing tools, including spot sales, forward contracts, hedging with futures, basis contracts, and options.

Finally, the guide suggests producers make a marketing plan and follow it, reviewing and adjusting based on changing market conditions rather than abandoning the plan at the first wobble.

Penner is hosting a one-day workshop in Saskatoon on Jan. 16.